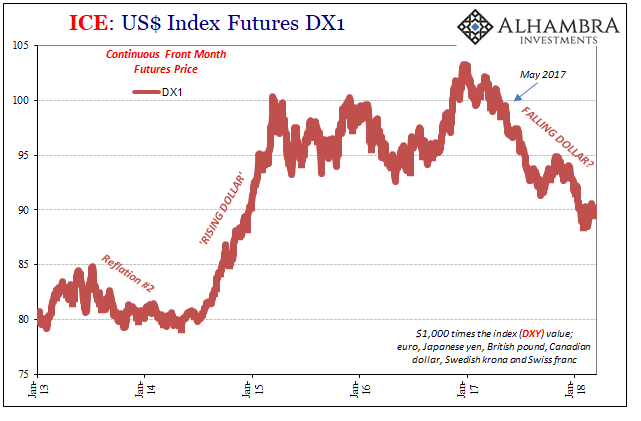

On January 24, Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin either misspoke or let slip a Freudian sort of wish. Extolling a weak rather than strong dollar, it was seemingly a total break from longstanding official US policy. It’s not really a policy anyone takes too seriously, if for no other reason than the dollar isn’t really a part of the Treasury.

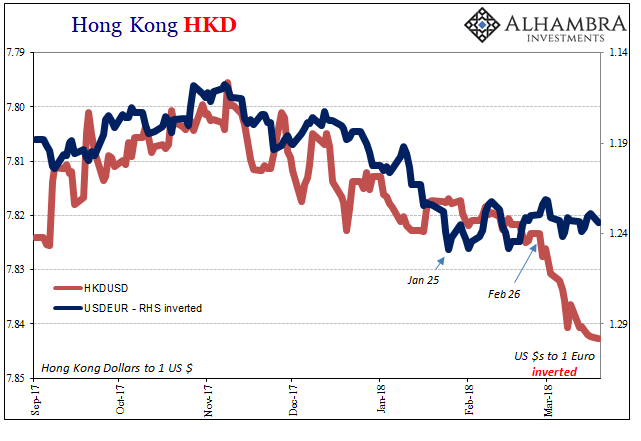

Still, the comments moved markets and led to all the usual hysteria, including of the recent inflation variety. Behind the Treasury Secretary’s comments was an unofficial acknowledgement – when the dollar falls in exchange value, the economy seems to do much better. Even if officials can’t really figure out why, the appeal of this correlation is obvious.

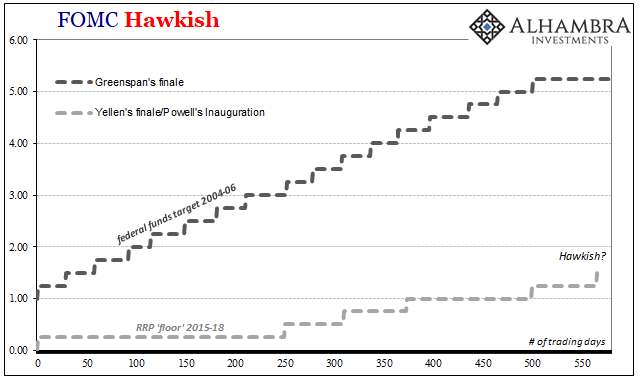

Jerome Powell just concluded his first “rate hike”, meaning that each of the last three Federal Reserve Chairmen have all contributed to the same exit process. Begun as tapering under Bernanke, QE was ended under Yellen who then began the “rate hike” progression. It will continue for the time being under Powell, though the markets aren’t as sure as he sounds about how it will end.

Whatever the future case, this past history is shameful. How can an exit process last through three Chairman across the span of just about five years and counting? You might get the sense that the economy isn’t so great, and that policymakers really don’t know what they are doing. Greenspan was no better when it came to money and bonds, but he completed 17 hikes in two years.

If you are somewhat lost especially when the unemployment rate is no help and you can’t figure out inflation, what might you anchor to in order to at least try and plot a plausible policy path?

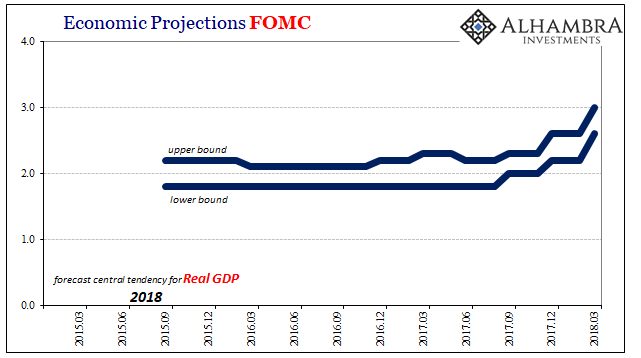

The FOMC models give us a big clue. Since the middle of last year, FOMC estimates for 2018 and 2019 GDP have been raised. The latest projections released today show that for this year at least the Fed is more optimistic about the intermediate outlook than it has been in some time.

The modeled central tendency for Real GDP in 2018 is now 2.6% at the lower bound, and 3.0% at the upper. It’s substantial improvement from where 2018-19 GDP estimates were when models began tracking them back in 2015. What changed around the middle of 2017?

The Federal Reserve would never follow the Treasury Secretary in his moment of apparent weakness. Jerome Powell’s responses to questions today were almost of the Greenspan variety of fedspeak – pretending to say a lot without saying much if anything. Some of that was stylistic, but a lot was a very real lack of clarity and good answers.

When asked about wages, the new Fed Chair admitted he and the Committee really have no idea what’s going on. Therefore, the models can be optimistic about GDP (unemployment rate) while at the same time expecting continued subdued inflation (not the unemployment rate). This confusion seems to place emphasis somewhere else, which is almost surely the exchange value of the dollar.

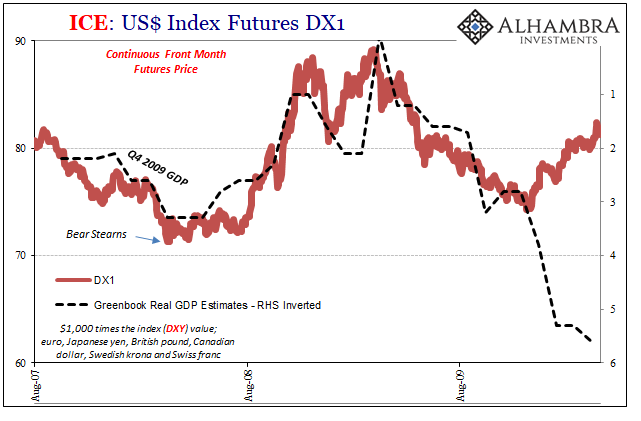

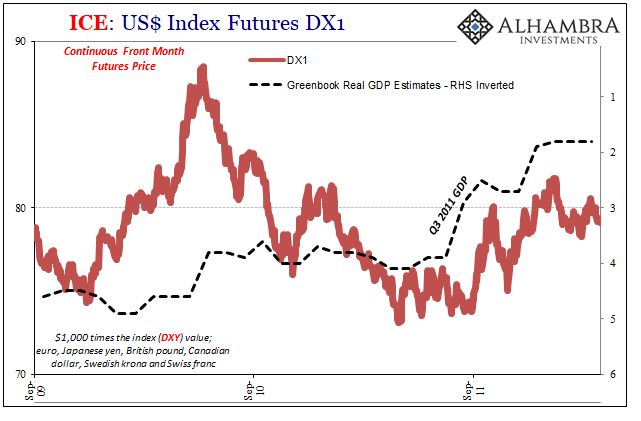

It’s not the first time modeled expectations have behaved this way. Using Greenbook estimates going all the way back to 2007, the relationship is almost uncanny. The dollar falls, the Fed’s models see better growth in whatever specific quarter (the track below is taken from successive Greenbook’s across several years, all for Q4 2009 Real GDP; the GDP estimates are inverted to better illustrate the inverse relationship).

In March 2009, the Fed’s Greenbook was predicting a negative number for that year’s Q4. The dollar had just then hit its highest value. As the dollar weakened again, even before the economy recovered, the Greenbook became far more optimistic about recovery. The divergence at the far right side of the chart above is simply the next leg higher in the dollar that happened toward the end of Q4 2009 and therefore was too late to influence the estimates, or the economy, for that particular quarter.

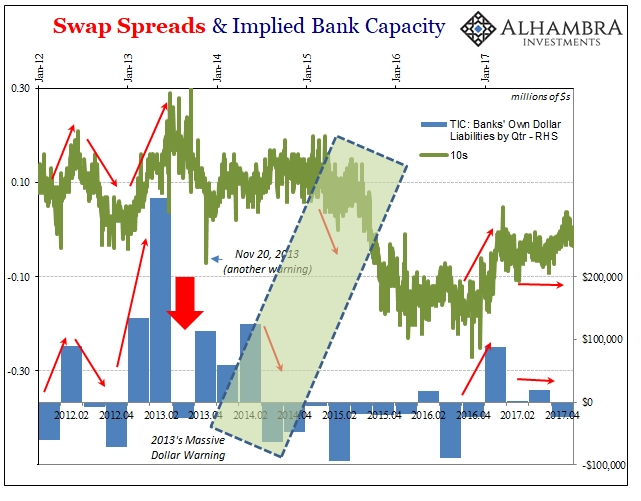

The clear correlation is everything we know about what sets the dollar value in broad or even specific exchange – supply and demand in offshore markets (eurodollars). Though policymakers appear unable to comprehend the reasoning, and the operational implications, their math at least figures the correlation if not the meaning or cause behind it; rising dollar = bad economy.

The real question, then, is why they tend to speak otherwise in public; especially 2014 and 2015. Perhaps it’s pure CYA, meaning that to admit the “rising dollar” is bad is to allow scrutiny a little too close to home. Better to meekly protest and appear unreasonably “dovish?”

The same process can be found in just about every quarter’s Greenbook track. Using Q3 2011, for example (shown above), the models start out (in late 2009) very optimistic about 2011 in general (5% growth).

Almost right away in late 2009 and through the middle of 2010, the dollar is rising again. GDP estimates are reduced in accordance with that signal until the middle of 2010 when the dollar starts weakening again.

As it falls in exchange value throughout later 2010 and early 2011, the Greenbook keeps GDP at least constant despite otherwise enormous questions about the state of the recovery and what’s really going on (leading to, of course, QE2 in November 2010). The end of the falling dollar in April 2011 prefaces the last cut in GDP estimates for what turned out to be an “unexpectedly” weak year.

Monetary authorities can’t answer basic questions about inflation and wages, but they are optimistic anyway for reasons they also can’t really explain. They appear almost certainly to be following the dollar. Whether or not they are cheering for it to decline is a political matter, or at least one for more private discussions.

That they have no idea how or why it falls, and therefore if or how it might once again reverse, is for the last decade a given. That’s why there’s three “rate hikes” in the dots for this year rather than the Greenspan pace of one per meeting, or the more confident prospect of eight total in 2018. The dollar is falling, they think, so they are optimistic. They don’t know why its falling and what makes it reverse, so they’re materially cautious.

There are no “hawks” nor “doves” here. There are only the whims of offshore money.

Stay In Touch