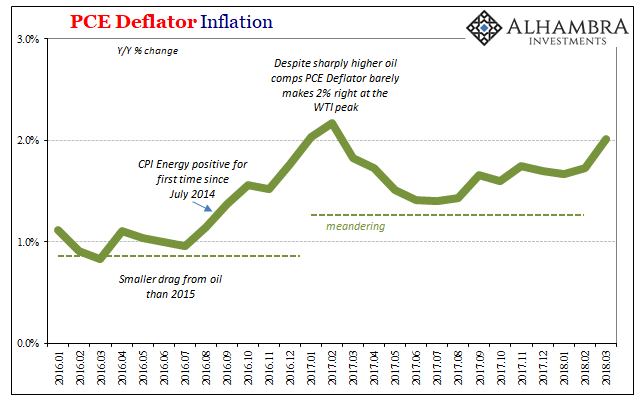

Credit where credit is due. In March 2018 for the third time in the last 71 months the PCE Deflator registered 2% or better. The year-over-year change just barely squeaked above that line, working out to about to 2.01%. I’m sure the FOMC will take it regardless. Baby steps.

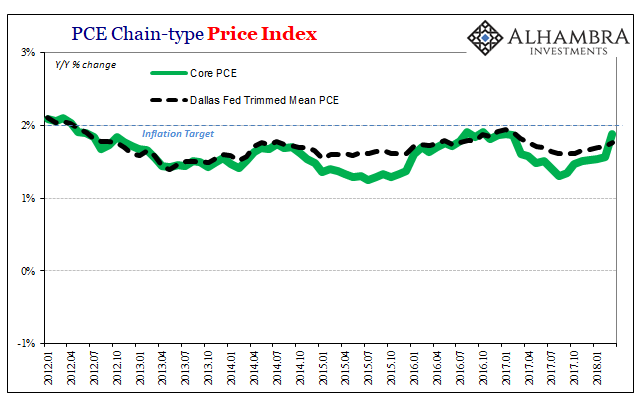

Core rates were slightly less, however. The Dallas Fed’s trimmed mean calculation rose only to 1.77%, while the PCE Deflator stripped of energy and food prices finally dropped the Verizon effect. It accelerated as expected, but only to 1.88%.

In other words, the only thing really moving the deflator up is WTI. It doesn’t matter for anyone keeping score, just as it didn’t matter that oil prices were the primary drag for it 2014-16. If you get penalized for the oil crash, then there is some benefit (in policy terms) to its continued reverse.

The real problem is keeping the inflation measure above 2%. It is in that respect that oil prices do matter, mostly because they suggest what isn’t in the deflator – the one thing policymakers have been waiting for. The Federal Reserve mandate, self-defined, is for sustained 2% inflation as what counts for price stability (low enough, they believe, so as not to steal too much from consumers, but high enough, central bankers still think, to keep some margin against outright deflation).

Three times over the last 15 months is better than the zero for the prior 56, but it doesn’t yet add up to their definition. In truth, it’s not really much different.

To get there, that’s why from Janet Yellen to Jerome Powell there has been an overriding emphasis on wage growth and more so rapid acceleration. The average price of WTI in March 2018 was $62.73 compared to $49.33 in March 2017. Therefore, unless oil prices are going to rise each month by 30% year-over-year and keep doing so for more than an occasional month here and there, the PCE Deflator just isn’t going to remain above 2%.

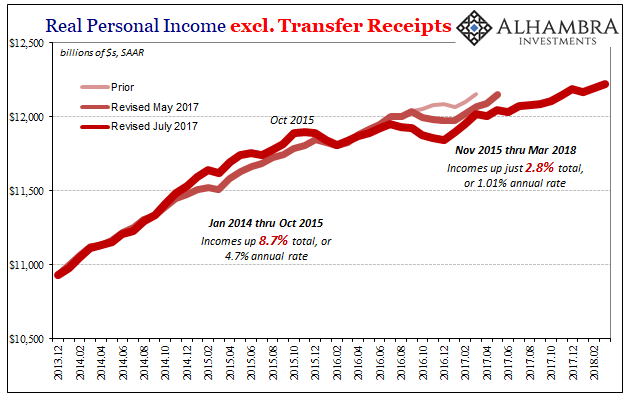

After all, despite that contribution from the 27% gain for oil prices in March, along with the merciful rolling off of transitory wireless data plan base effects, the PCE Deflator still only barely made it to the 2% level. What would keep it there is actual economic growth, a condition that is just not possible given the true baseline state of the economy (income).

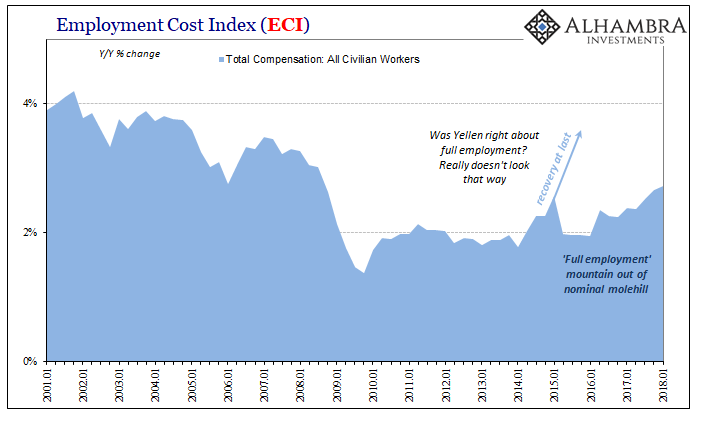

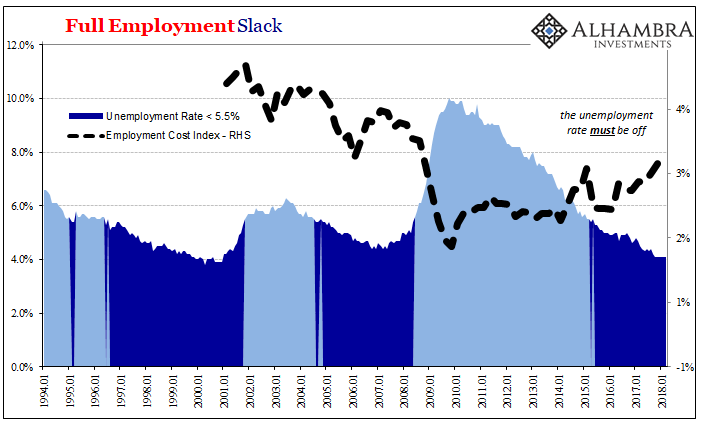

Wage acceleration would indicate that perhaps things are changing in a deeper and more meaningfully positive direction. The forecast end of slack (which, it must be pointed out, has been forecast for four years now) should it finally prove true could suggest a plausible path for monetary policy to achieve its goal (still no guarantee). An actually tight labor market should improve income growth by more than the statistical variations we’ve observed for years.

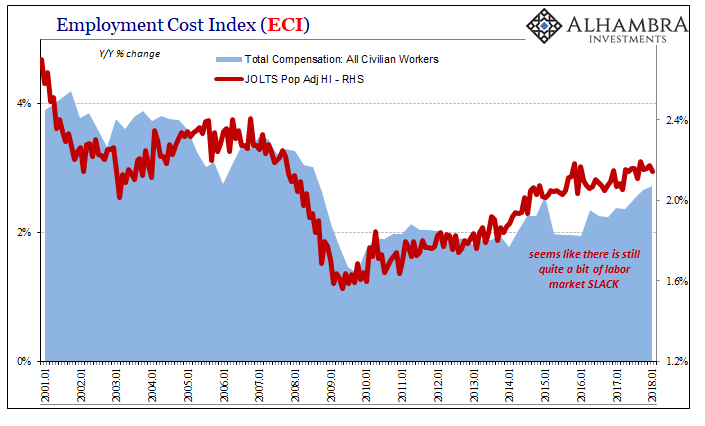

The problem is that there just isn’t any evidence we are close to that level, or are even making substantial progress toward it. Last week concurrent with the BEA’s release of Q1 2018’s “unexpected” GDP disappointment, the BLS calculated its Employment Cost Index (ECI) which rose year-over-year by the highest rate since 2008. Like so many other related factors, the best in a decade just doesn’t mean as much as it might sound.

At 2.71% year-over-year, the ECI was not meaningfully different in Q1 2018 from the 2.66% in Q4 2017; despite another 6 months with the unemployment rate substantially below mainstream definitions for full employment. Rather, 2.71%, like the low level of many other wage growth indications, suggests substantial slack still.

Even this continued miss obscures to a certain extent the bigger problem. If businesses are paying a little more per worker, which it appears that they are, then they are balancing that out by increasing their payout for all workers by less overall (hiring fewer new ones, and working the ones that exist a little bit less). That’s the only way to get from slightly accelerating worker costs (as noted by the ECI) to much slower aggregate (labor) income growth.

These are all suggestions of continued economic restraint, especially as it pertains to labor. The FOMC should not, and likely does not, at least in private, expect the 2% mandate to hold until this one crucial part changes. They keep saying that it will, and we keep waiting for it to show up. Like the two in 2017, a third oil-driven PCE Deflator takes some of the pressure off but it’s still missing the actual boom and not really close enough to kick off one.

Stay In Touch