This past weekend saw many occasions around the world mark the 200th anniversary of the birth of Karl Marx. Rather than lament the rise of one of the most destructive influences of the modern world, most if not all were quite celebratory. The much-loved philosopher, especially in academic circles, has for his followers given them an outlet for revival.

It began in 2008. Panic gripped the world, markets crashed, and the economy collapsed. Leftish media outlets could barely contain their approval upon reporting how sales of Marx’s volumes were up sharply, particularly the big one Das Kapital. What that meant was far more than reported 300% sales growth.

Increasing numbers of Germans appear ready to out themselves as Marx fans in a time when it is fashionable to repeat the philosopher’s belief that excessive capitalism with all its greed finally ends up destroying itself.

That story appeared in the UK on October 15, 2008, in the immediate aftermath of the second wave of panic (there would follow a third in early 2009). Just eight days later, former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan was called up to Capitol Hill to testify about the mess. He apologized for it; sort of.

“I have found a flaw,” he said. He didn’t identify the flaw as himself or his successor, but the free market doctrine of self-interest.

I made a mistake in presuming that the self-interests of organizations, specifically banks and others, were such that they were best capable of protecting their own shareholders and their equity in the firms.

The implications were Marxist, or at least favorable to his restoration. Free markets had failed, Greenspan claimed, self-interested capitalism had been the cause of much suffering and damage just as Marx had claimed it would. In 1857, Karl had written to Friedrich Engels, his oftentimes partner, greedily recounting, “The American Crash is a delight to behold and it’s far from over.” He thought Wall Street would perish, and America with it (it nearly did).

Yet, Wall Street survived. So did the United States. They thrived, even. One of these days, though, maybe, just maybe Karl the stopped clock might be right.

Capitalism is messy and prone to business cycles. It is also unequal in its distribution, sometimes heavily. The argument in favor, however, need not be explained to an honest assessor of the modern world. As John F. Kennedy used to argue, a rising tide lifts all boats.

What happens when the tide stops rising? That’s when Marx becomes popular again, just as he was in the thirties. It’s not coincidence that Communism globally was at its apex was during the Great Depression. When the economy doesn’t grow and for an extended period of time, people quite naturally begin to seek out answers even from thoroughly discredited doctrines.

Appearing Saturday in Trier, Germany, at the hometown celebration of the Father of Communism, the current EU President Jean-Claude Juncker told the audience of 21st century Europeans they should not judge Marx by what truly horrific acts his followers had committed in his name.

Karl Marx was a philosopher, who thought into the future, had creative aspirations, and today he stands for things which is he not responsible for, and which he didn’t cause, because many of the things he wrote down were redrafted into the opposite.

After his speech, Juncker further assured the assembled reporters, “Marx is not responsible for any crimes for which his alleged heirs should answer.“ That is true, but only to a limited extent. Ask yourself, how creative could he have been if all those who have followed him the closest, those who have had the most interest in doing so faithfully, each and every one of those times it ended in utter ruin and despair.

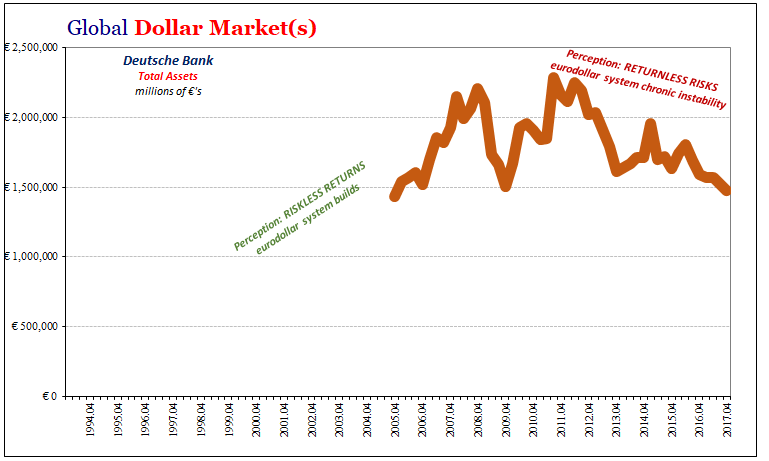

Marxism cannot be a robust philosophy if after all these attempts they only leave supporters disavowing them. It wasn’t real Communism, they always claim afterward. Chavismo, for a recent example, was hailed as a true and faithful revolution, until it wasn’t (dictated by the direction of the eurodollar).

The problem isn’t really Communism, per se, it continues to be Greenspan. That brief and intermittent flirtation with Marx during the panic in 2008 should have ended there, as it had in every other episode in the past (there was very brief outbreak after the Crash of ’87, for instance, open letters written to announce the destruction of Wall Street 130 years after it was first heralded by their Master). But 2018 is ten years and no economic recovery; the tide stopped rising a decade ago.

Was it really banks that were to blame? Yes, but only partially. No one can nor should excuse the worst excesses, and we need to realize that there were a lot of them that could be categorized that way. But that’s only part of the picture. Why did banks take so much risk? Or, another way of asking the same question, how could risk, particularly liquidity risk, be so completely mispriced by nominally free markets?

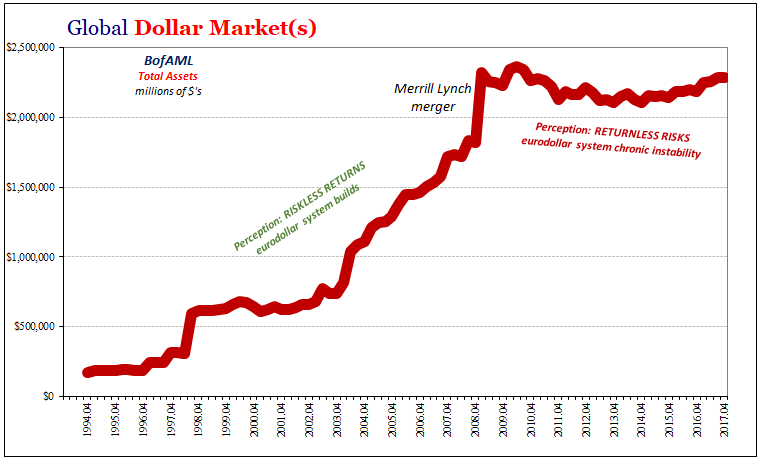

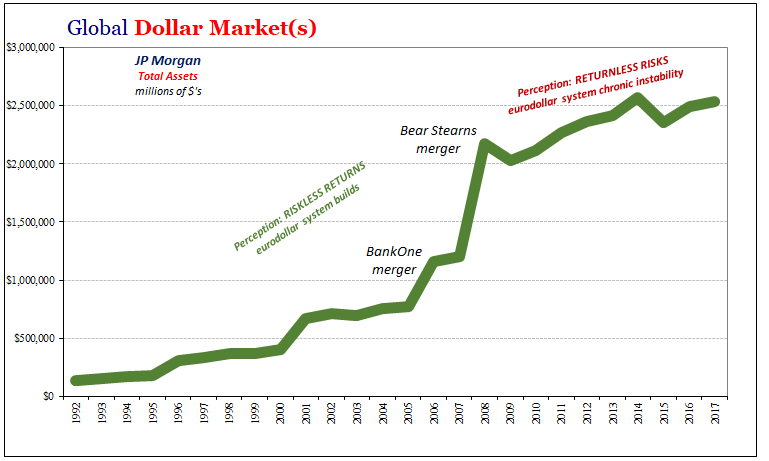

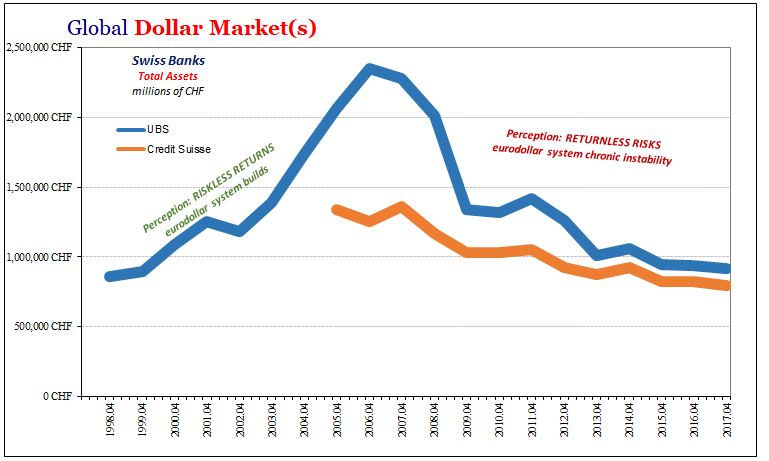

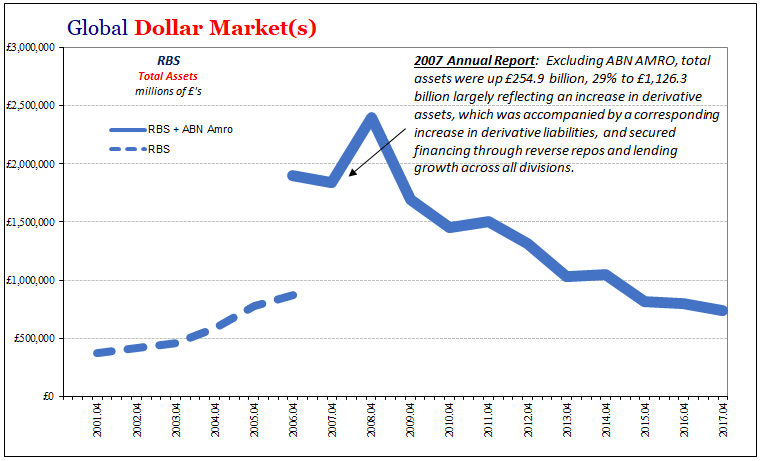

This is an inquiry that doesn’t fit into a single article on the subject, of course. To put it briefly, they did so in large part because of the so-called Greenspan put. There were other reasons, too, related reasons that all tied together along the lines of a poorly understood liquidity doctrine. The eurodollar system had presented the global banking system with what appeared to be a robust framework of redundant structures and backstops; the ultimate of which was the Federal Reserve that everyone faithfully believed would bail it all out should push ever come to shove.

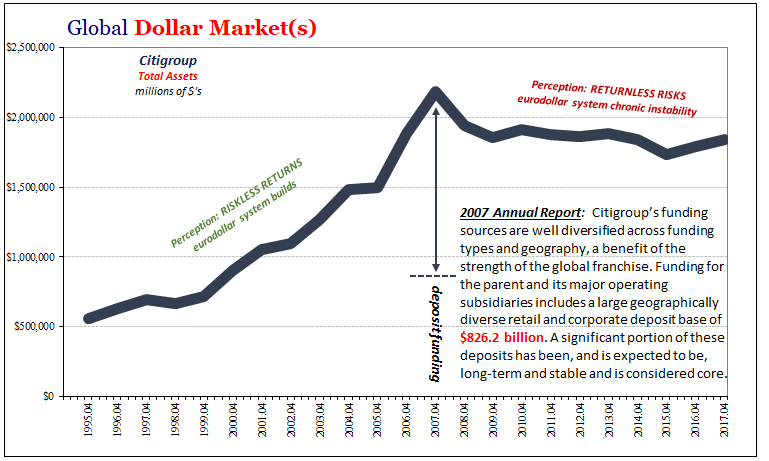

This is the topic that I will explore with Erik Townsend of MacroVoices in the upcoming Eurodollar University Season 2 (I’ll post notifications for when it will be released). Banks never would have taken such extreme steps with things like subprime if they had ever developed a more realistic sense of the weaknesses in the global monetary architecture. That’s why the failure of Bear Stearns proved so decisive in the systemic reversal; Bear demonstrated that there was no Greenspan put, a possibility banks after August 2007 had begun to suspect, and the consequences of it was complete failure (it wasn’t subprime that collapsed Bear) for individual firms as well as the whole.

To me, that wasn’t capitalism nor was it free markets. It was a hybrid which superimposed deeply ingrained monetary ignorance. Banks under the Greenspan put believed that regulators and central banks controlled and dictated systemic money risk, while at the very same time regulators and central banks viewed the monetary system as an area not worth any study or attempted accuracy.

How could have “markets” so mispriced risk? Greenspan’s wholesale adoption of Positive Economics.

The result is that Marxists have been gifted both sides of the Panic. The pre-crisis era is characterized as out-of-control capitalism, while the lack of recovery and worldwide economic malaise that has followed is easily painted as the consequences of it. Just as Marx predicted. A lot of them have started to claim this time he might be right, and to heavy throngs spread throughout the world, for the first time in eighty years it starts to sound plausible.

In one additional but absolutely necessary contribution to the Communist revival, central bankers, these disciples of Greenspan, have sought constantly and consistently to deny there is any economic problem at all (as little more than transparent CYA). The effect of which has been to sow greater and greater mistrust, creating the very vacuum into which so much renewed enthusiasm for Marx can follow. To have Greenspan proclaim, “the banks did it, it wasn’t my fault” only stamps the imprimatur of official acknowledgement onto the theory.

The economic costs of the eurodollar breakdown have already been suffered. The ongoing global economic problem, this worldwide “L”, only adds to the already-presented bill. The issue is now far more than lost economy.

It’s easy to just dismiss all this Marxism stuff as the constant dreams of the utopian classes, the historically illiterate trying desperately for revisions as they always have. The problem is that without a rising tide we can understand why people might start to overlook history’s clear judgment. But that’s merely the symptom. The real problem is the absence of the rising tide.

Stay In Touch