At a campaign rally in New Mexico in May 2016, Presidential Candidate Donald Trump returned to one of his favorite themes. It was a package deal. He first talked about NAFTA and what he considered the negative effects the trade agreement had had on American workers. That easily segued into what had by then become a campaign staple, the unemployment rate.

You hear a 5 percent unemployment rate. It’s such a phony number. That number was put in for presidents and for politicians so that they look good to the people.

People view the election of Trump in a lot of different ways. For me, it was a positive sign for reasons like this; the economy and labor are by far the biggest issue we face because of the internal discontent it can only bring if it is allowed to fester and continue. Finally, in 2016, someone was going to look at the problem and finally give it the honest accounting that is required. From that fresh perspective, perhaps breaking with convention and seeing the economic condition for what it is, and more importantly finding out why it has been this way.

Everyone is talking about the latest Presidential tweet that some say breaks federal rules. I could not care less about it other than to see how it betrays the focus that Candidate Trump possessed. It was that voice given to the “not in the labor force” American which I believe put him over the top in the first place.

Unemployment rate only dropped because more people are out of labor force & have stopped looking for work.Not a real recovery, phony numbers

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) September 7, 2012

Looking forward to seeing the employment numbers at 8:30 this morning.

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) June 1, 2018

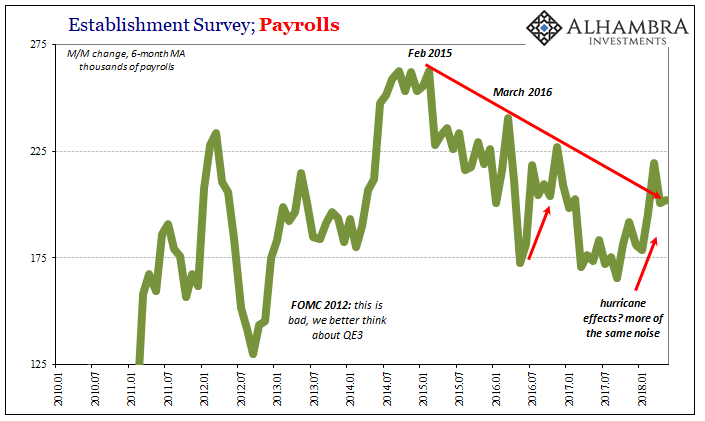

The tweet issue, for me, isn’t when it was published rather it is how the President has apparently embraced the easily disproved canard that somehow a +223k monthly payroll number is a good one. It’s not. It’s not even close.

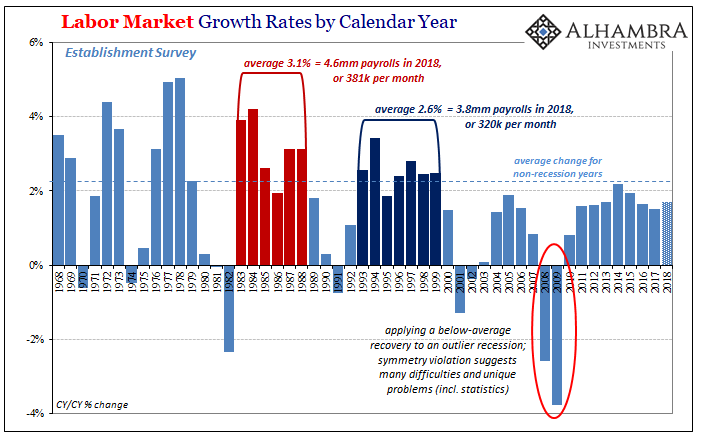

The Establishment Survey has ticked up a little so far in 2018 from the gains in 2017. That by itself means nothing. Last year was an objectively bad one for American labor, so being better (through May 2018) isn’t some great achievement.

When private citizen Trump tweeted about the labor force (above) in 2012, the BLS estimates that the Establishment Survey grew by 1.61% that year. It was not a good year for any part of the economy. Even the perpetual optimists at the Federal Reserve were for once (or the third and fourth times) inclined to agree. The FOMC voted for two more rounds of QE to try and do something about the looming near recession of that time.

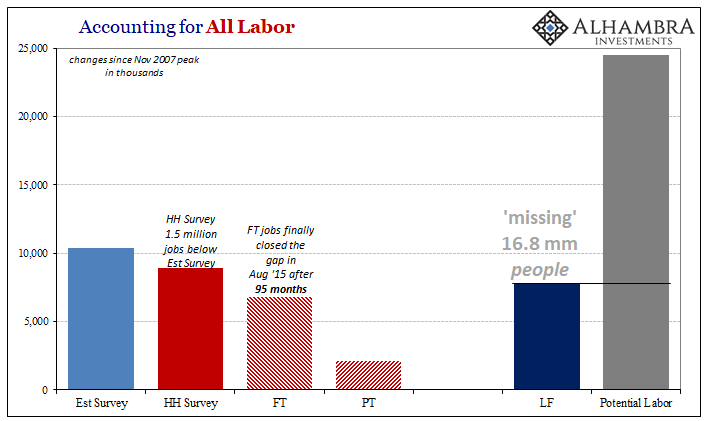

In 2017, payroll gains were downright abysmal; just +1.50%, worse than when more QE’s were being applied. A truly healthy year would have been something like the late 1990’s when the average was around +2.6%. In current terms, merely a decent month would be one that would display about +320k in gains, not +220k. An actually strong month would be something like the mid-eighties, translating into almost +400k in today’s population.

As of May, the Establishment Survey has averaged just +207k for the five months of the current year. Again, that’s a little better than last year, but if it holds at this pace for the balance of 2018 it would still only amount to +1.69%. That’s not meaningfully different from last year nor 2012 which provoked something like panic in Ben Bernanke.

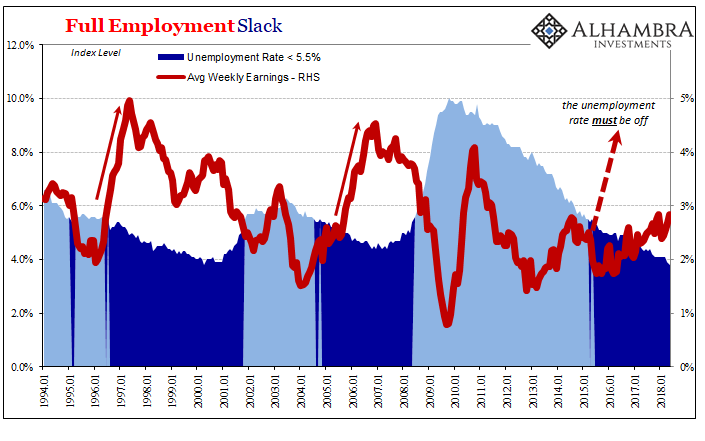

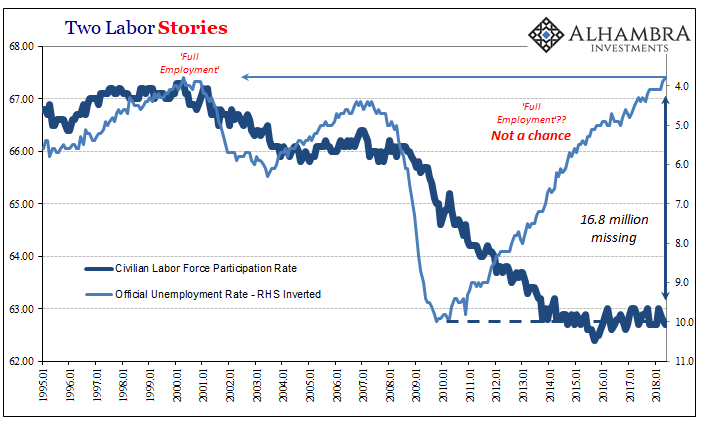

As usual, the consequences of truly no growth in the labor market leaves particularly politicians to emphasize nothing other than the unemployment rate; Candidate Trump was absolutely right about that. But if it was fake at 5% with no evident wage acceleration, what can it be at 3.8% as it is calculated for last month?

There is still nothing to indicate an end of labor slack, leaving anecdotes about a labor shortage the same as always – anecdotes. At any given moment under any given economic condition, you can find some company that will be having trouble finding workers (the issue is never finding them, it’s about paying them a market clearing rate). Turning those anecdotes into some widespread macro phenomenon without further evidentiary corroboration because the unemployment rate is so low is irresponsibly misleading.

It requires the same transformation that first sowed so much distrust to begin with, and that ultimately propelled Mr. Trump to the White House. Prioritizing the unemployment rate means characterizing every small and often meaningless gain as something it is not. Again, +223k is a bad month, certainly not one risking breaking federal rules for, especially as it follows +155k and +159k March and April (revised), respectively.

If the jobs market was truly a strong one currently, there would be a clear rush of those not in the labor force to join it. Opportunity is not solely a financial parameter, it is first and foremost an economic one. Those millions right now outside the official numbers would be moving back into them if they were given a legitimate shot at fruitful employment.

The labor force barely budged in May and going back to last September (when things started to heat up in the eurodollar world) it has grown by all of +457k (and that total includes a likely statistical discontinuity in January of +518k). In other words, over the last eight months the labor force has shrunk by proportion of the population again even as the unemployment rate falls to levels not seen since the dot-com era – the unemployment rate drops because nobody is joining the labor force.

It is exactly the complaint Mr. Trump expressed in his 2012 tweet. The one guy who was finally willing to be honest about the state of American labor appears to have become just as conventional as the all the rest. The unemployment rate tells us nothing of use, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t useful. Sad.

Stay In Touch