On June 13, the day the eurodollar futures curve inverted, Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell was at his regularly scheduled press conference following the regularly scheduled FOMC meeting. Nobody asked him about eurodollar futures, of course, because why bring that up? The press did inquire about IOER, though. The Fed had decided to make a “technical adjustment” in its policy for ostensibly controlling money market rates.

The tortured history of IOER wasn’t reviewed. Instead, the Chairman deferred to some procedural issues in federal funds. At least that is what he called them. Sticking to the T-bill deluge lie, the Fed, Powell noted, would adjust IOER by 5 bps the next day.

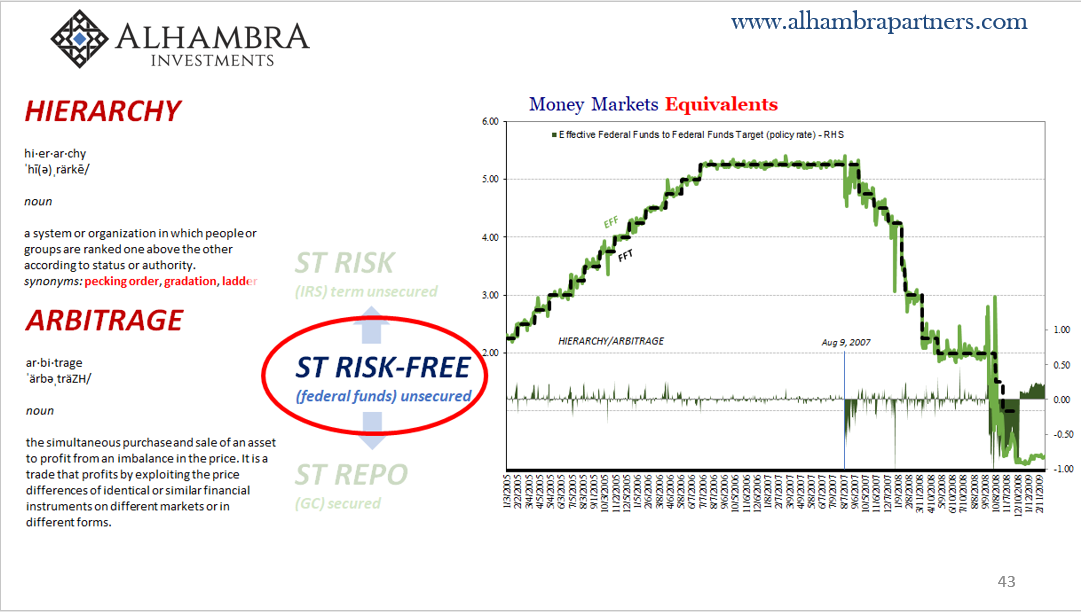

Ever since the debacle of 2008, the technical framework for monetary policy has been different – though not necessarily for the reasons you might imagine. It remains one of the more unexamined aspects of the global monetary breakdown, this full-blown rebellion in federal funds.

For a good long while at the worst possible times, the federal funds rate was untamable. Nothing the Fed did including the introduction of IOER made any difference. This was no minor deviation, though very few know anything about this part of the affair. It goes straight to the fundamental properties of the modern money system every central bank gets wrong – which is why it was the central basis for my speech in Toronto on August 10 (I’ll post the video for it soon).

This breakdown in predictable hierarchy describes very well what’s wrong with the global monetary system. That, obviously, isn’t the judgement of central bankers like Jerome Powell, therefore “technical adjustments.”

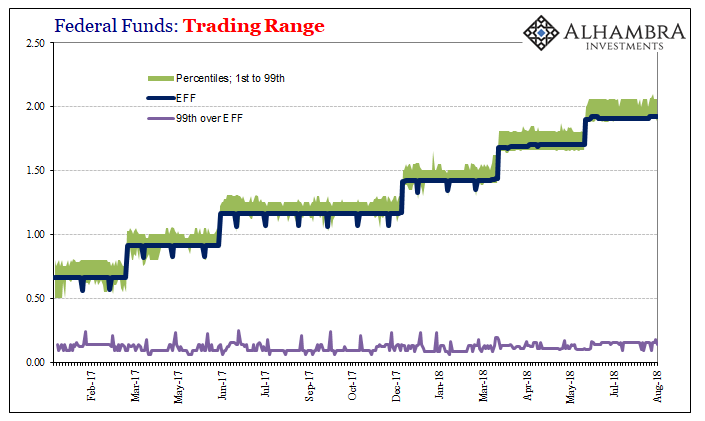

The immediate 2018 problem is that the effective federal funds (EFF) rate is getting too close to the top. Rather than a single federal funds target as had existed from the 1980’s until 2008, the FOMC now sets an acceptable range. To enforce the limits of that range, the reverse repo rate is positioned at the bottom (which hasn’t really held up either, though not in direct relation to federal funds) and IOER on top despite its uniformly awful past performance.

When the FOMC voted for its last “rate hike” of +25 bps back in June, in order to pressure EFF back toward the middle and away from the top IOER was only raised by +20 bps. That additional 5 bps was supposed to be one-for-one.

Powell’s response at the press conference to questions about IOER was the usual whistling past the graveyard. “We don’t expect to have to adjust IOER often.”

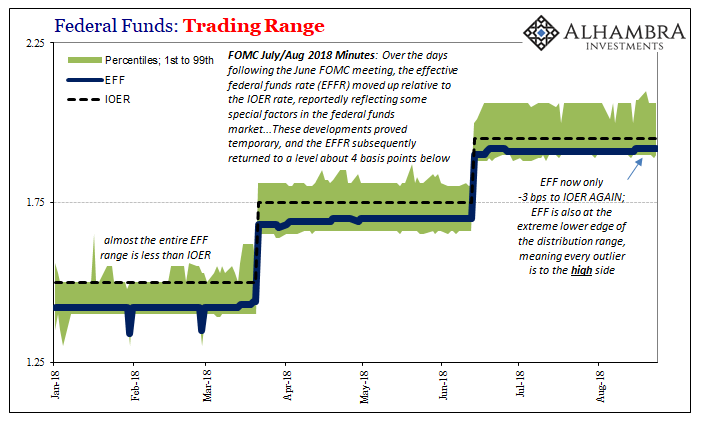

Within a few days, however, EFF was at 1.92% having closed within 3 bps of IOER despite Powell’s assurances. The 5 bps technical adjustment was meant to have kept it at a – 5 bps spread. It then settled down to – 4 bps, which at the following FOMC meeting (July 31/August 1) was judged to have been an acceptable if non-technical distance.

From the July/August FOMC minutes released last week:

Over the days following the June FOMC meeting, the effective federal funds rate (EFFR) moved up relative to the IOER rate, reportedly reflecting some special factors in the federal funds market, including increased demand for overnight funding by banks in connection with liquidity regulations and a pullback by Federal Home Loan Banks in their lending in the federal funds market. These developments proved temporary, and the EFFR subsequently returned to a level about 4 basis points below the IOER rate.

I would have preferred the language of “transitory” because under the new 2015-18 central bank definition of the word EFF has behaved exactly like it. In other words, the -3 bps spread re-emerged again last week proving it wasn’t transitory at least in how the term had ever been used in any other context outside of monetary Economics. As of Friday, EFF is 1.92% for the seventh straight session.

Contrary to Powell’s casual dismissal, rumors have been swirling that the FOMC might have to make another technical adjustment to IOER when it next “raises rates.” That assumes, of course, EFF doesn’t deviate another bp or two before then. What might an intermeeting IOER adjustment add to the current environment?

The real problem, the one everyone around the world is trying very hard not to grasp right now, is what I wrote on June 11 in the smoldering aftermath of May 29:

To be clear, I’m not saying that tightness in federal funds was the cause of all or even any of those things. It almost certainly wasn’t. Instead, what is more likely to have happened was how global “dollar” tightness was so severe at times it actually registered very close to home (for the FOMC) in an out-of-the-way money market. If it hit in EFF, what does that say about the scale of the problem outside of there where it might instead really matter?

Federal funds is a dead market (which tells you a lot about monetary policy). If eurodollar disruption registers there we can only conclude that it must’ve been substantial. If the ripples of effective money disorder reach all the way out to the farthest ends, how strong must they have been at the center? We know that more and more in hindsight as additional statistics come in (particularly about May 29).

What, then, does that say about the last week and a half when EFF is again -3 bps to IOER?

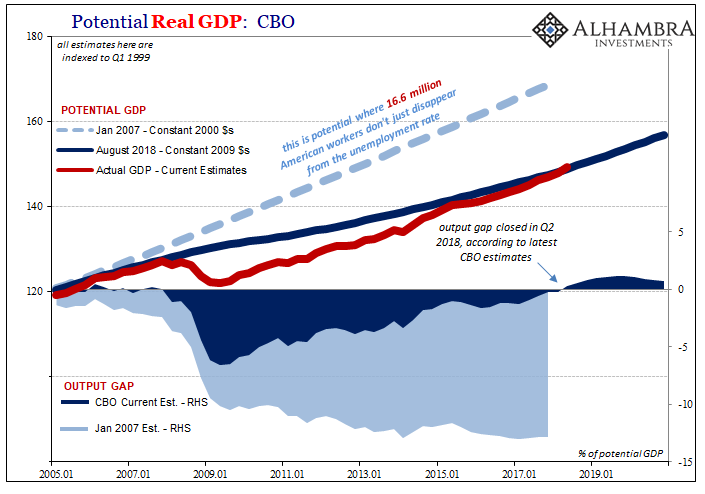

The Fed has gone through so many technical adjustments over the years they long ago stopped being technical. They never were technical. This is a fundamental issue. When Jay Powell figures out federal funds, if he ever does, he might then have a chance at solving the real thing rather than cheating his way into a recovery that doesn’t exist, and one that is getting darker by the technical adjustment.

Stay In Touch