In November 1929, faced with the growing prospects for serious economic reverse, President Herbert Hoover gathered the heads of major American industrial businesses to confer at the White House. Primary on his agenda was wages. For workers, depression was simple. Work was hard to find but more than that what labor might be exchanged would be paid for at a much lower rate.

This was the pernicious final defect of a deflationary depression. The downward spiral would always begin elsewhere, but it was the labor class who paid the final bill.

Hoover, far from the do-nothing history has colored of him, wanted concessions from business leaders that at the very least they wouldn’t take that final step. In his memoirs, the President would later write of the conference:

…to maintain social order and industrial peace…a fundamental view (is) that wages should be maintained for the present…that the available work should be spread by shortening the work week…the industrial representatives expressed major agreement…the same afternoon I conferred with the outstanding labor leaders and secured their adherence to the program…this required the patriotic withdrawal of some wage demands…

It was a mutual pledge; businesses wanted some steady assurances knowing full well that depression would mean hardship on every front, including major and even general strikes as they pared back worker costs. The labor side wishing to alleviate some of the pain of downturn agreed to peace if it might mean holding the line on pay rates.

It wasn’t to be, however, as everyone underestimated the looming catastrophe. If Hoover should be blamed it wasn’t that he did nothing it was that he did what everyone else thought needed to be done.

By 1931, it was already too late. Ernest Weir, Chairman of National Steel, in February of that year condemned what had become widespread wage cuts for, in his view, delaying a recovery from the still-somehow unfolding contraction.

…modern thought … is that the standard of wages determines the standard of living.

Just two months later, on April 6, 1931, Goodyear would ostensibly announce the beginning of the worst. The company would take 5% to 20% salary reductions for 13,000 of its workers. The hardest hit were, as is usual, the unskilled laborers with little natural economic protection against the ravages of depression. The very next day, BF Goodrich declared practically the same measures for its workforce.

Businesses will not sit idle and go bankrupt. Faced with losing prospects on their toplines, they will cut back as much as needed for as long as needed. That means cutting the number of workers as well as how much they may pay each of those who remain.

Orthodox Economics, however, only views this brand of deflation in this one way. What I mean by that is even monetary deflation is treated as it if it can only turn out like 1929. There is economic growth, or economic collapse, no possible gradation in between. This is how the 2% inflation target has been manufactured out of the second half of the 20th century.

Central bank Economists have come to believe that a little positive inflation is insurance against this worst case. If consumer prices are growing steadily at around 2%, there is small chance that the economy can fall into deflation largely because, Economists believe, monetary policies will catch the economy before it gets there.

Therefore, the real insurance isn’t 2% inflation itself, rather it’s the idea that 2% is enough of a buffer for central bankers to recognize the problem, craft solutions to it, and then implement them. As with everything, the central bank is theorized as central. But what if central bankers don’t know there is a problem, or, once reluctantly forced to admit the mistake, aren’t able to adequately respond?

Deflation.

This is where the modern day Cassandras are unhelpful, even the few who might be worried about the right things. In Economics, deflation can only lead to a “spiral” where the end result is 1930, 1931, and 1932. There are enough historical counterexamples demonstrating often great nuance, but one in particular stands out: Japan.

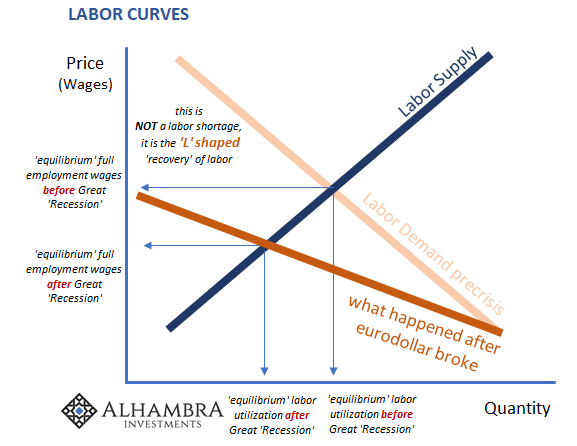

What if instead of facing deflation in a 1930’s sort of way, businesses refuse to raise wage rates and hire new workers going forward? They might not need drastic reductions producing the most drastically negative results. Rather, modest deflation might call for more modest corrective reactions, a sort of employer strike.

It preserves the long-standing elements of symmetry, namely that a huge money deflation would naturally lead to atypically large responses. Over the last eleven years in the US, deflationary pressures have been far more variable; to the extent that consumer prices haven’t been actually negative all that much. The PCE Deflator contracted for seven months in 2009 and was near-zero but still positive for a ten-month stretch in 2015.

No downward spiral(s). And for that, central bankers have been congratulating themselves for over a decade having presumably avoided replaying 1929.

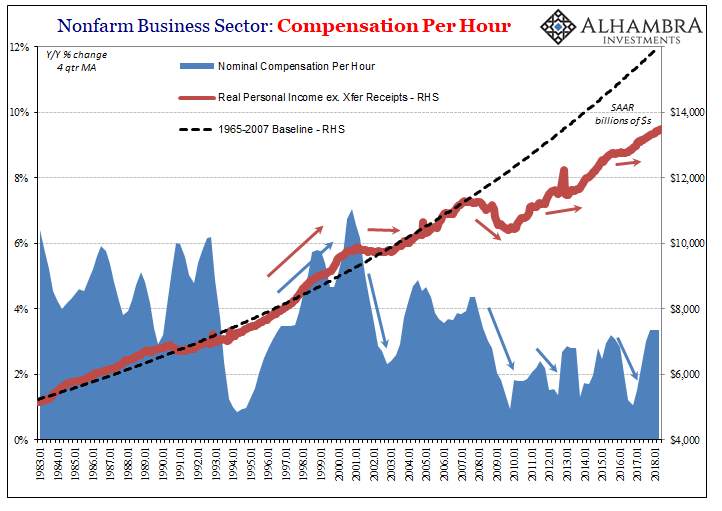

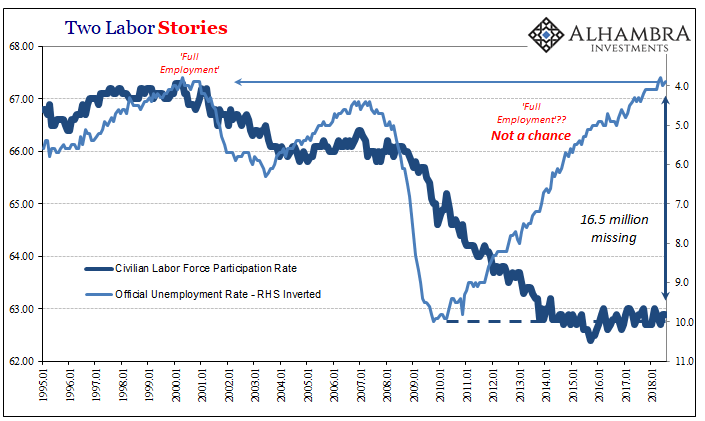

Yet, apart from the scale the last decade has turned out with many of the same qualities especially when it comes to the labor market. Economists and central bankers are stumped that wages haven’t exploded. Every day we hear about some creative way companies are dealing with a massive and now protracted labor shortage. A real labor shortage, however, requires no creativity to solve – raise pay to the market-clearing rate.

What we find in terms of data is confounding to the unemployment rate and backslapping central bankers. Deflation is evident everywhere. It’s not 1929-style, to be sure, but it’s right there. The employer strike has taken to both sides, the obvious reluctance to raise wages at the same time American labor sits idle in a way it hasn’t since the Great Depression.

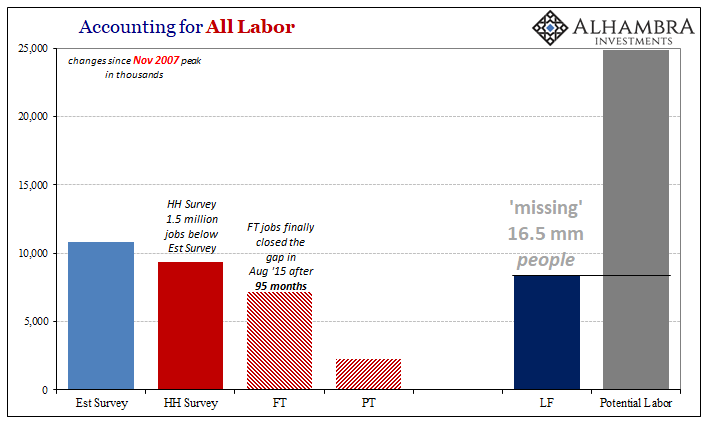

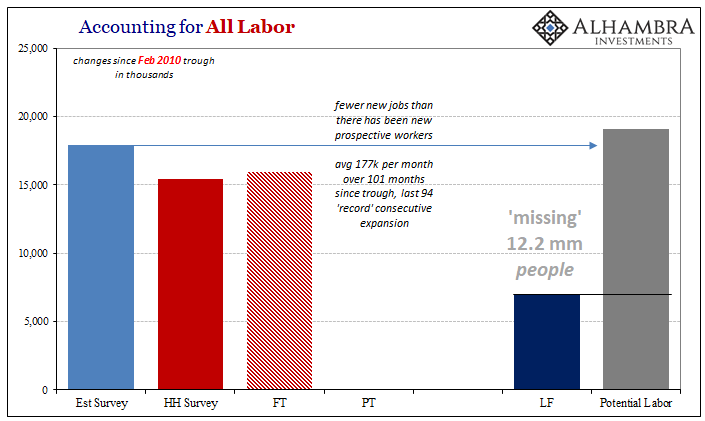

Since February 2010, the theoretical bottom of the Great “Recession”, there have been 17.9 million new payrolls (Establishment Survey) created. That sounds like a lot, but it’s not. At that rate, the US economy doesn’t even keep up with (slower) population growth let alone be able to re-absorb the millions laid off during the obvious contraction portion (2008-09).

Economists see these disparities, too. But they’ve now decided that there is something wrong with society as opposed to what they do, and have done. Drug addicts, lazy Americans who won’t go back to school, and retiring Baby Boomers. These supposedly add up to where the economy just operates very differently than it did before.

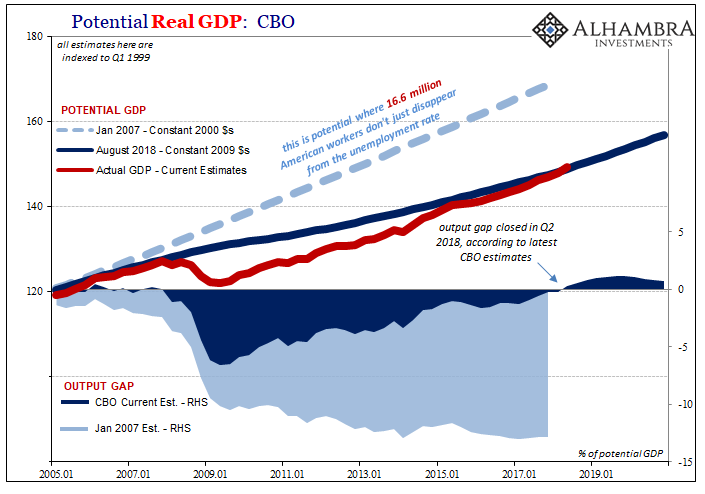

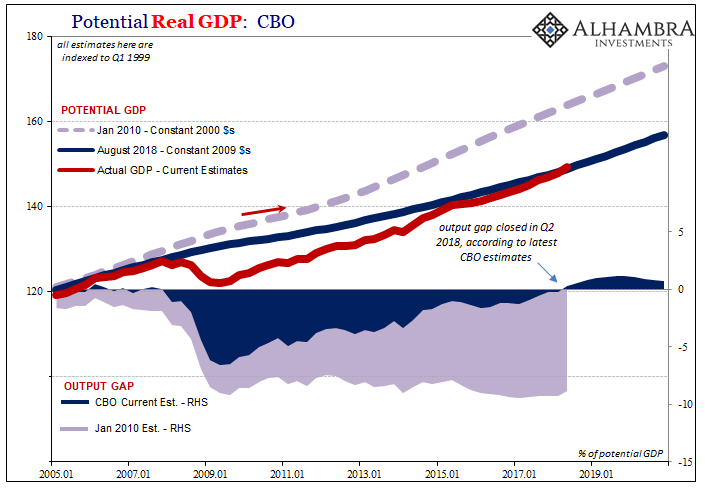

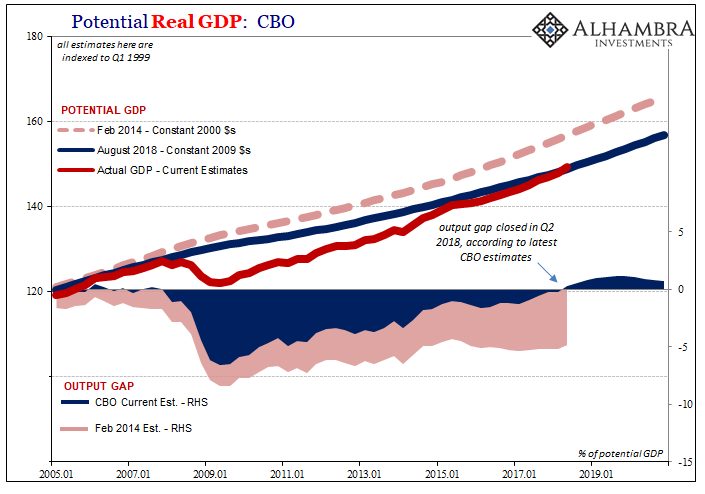

This is pure corruption. We know it is because of three very straightforward elements. The first is how Economists using these “explanations” still can’t account for how it all goes so wrong. They keep having to write down even more economic potential supposedly dulled by Americans’ collective lethargy every year, year after year.

They never once warned us there would be no recovery because the labor market was changing, instead they’ve now declared recovery using those excuses to justify the word in a way it was never intended.

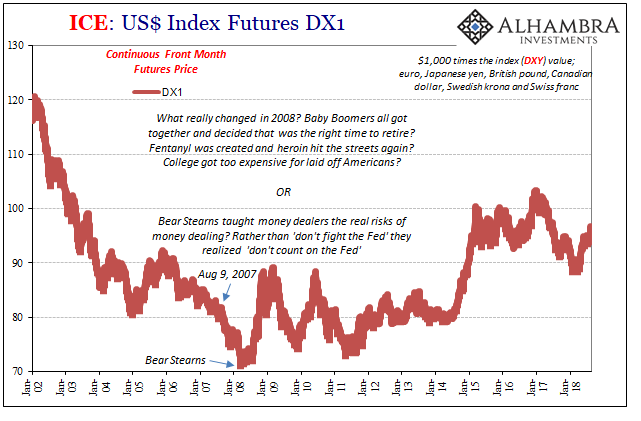

The second is the timing. Why did everything change starting around 2008? What happened in 2008 again? Economists, especially those attached to central banks (meaning almost all of them), would prefer not to talk about it except in how 2008 wasn’t 1929. The former wasn’t nearly as bad as the latter, but we will still be talking about 2008 over the decades to come the same way they once obsessed about 1929 for a long, long time after it was over.

Finally, this is not an US issue alone. The employer strike is a global one. In some places, such as Brazil, it was like 1929 only not in 2008 but in 2015. Deflation is, and has been, variable.

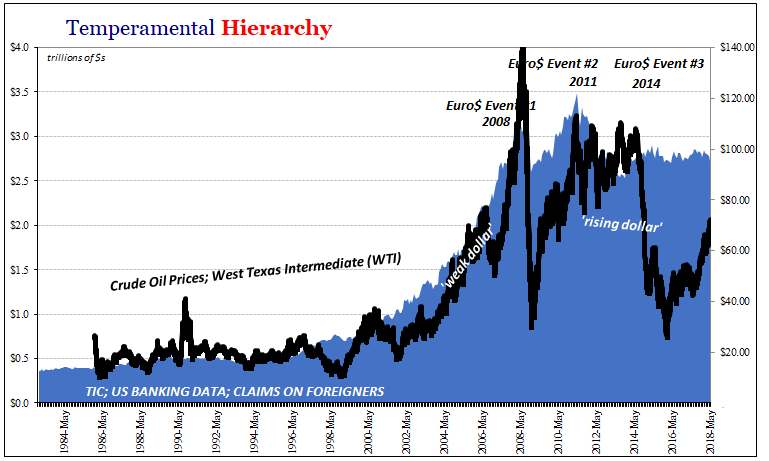

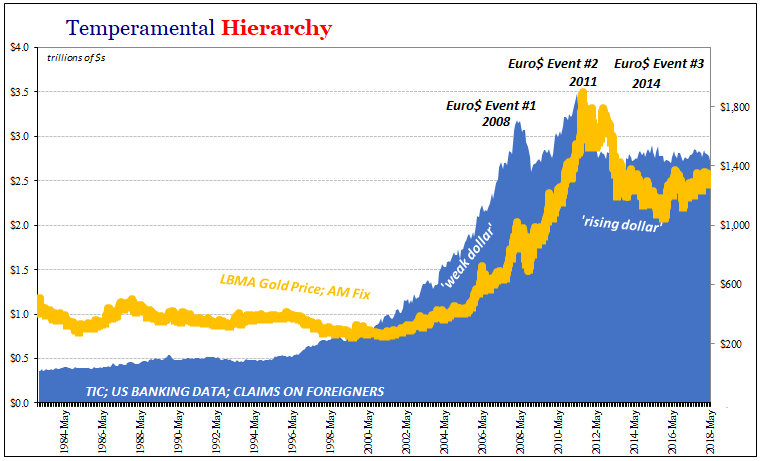

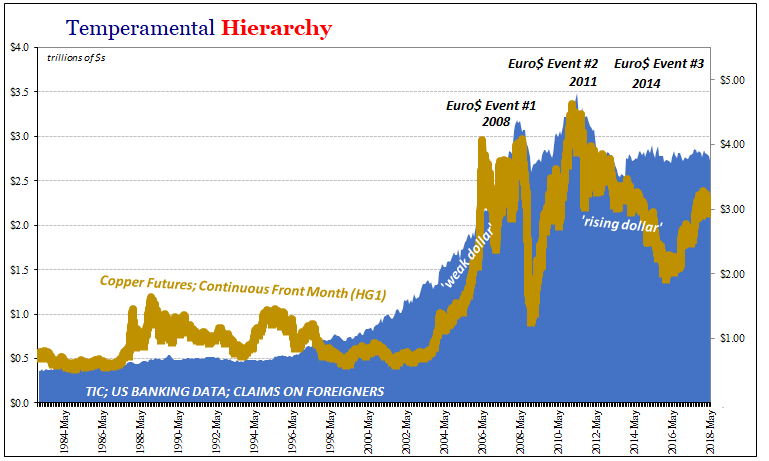

The effects, unfortunately, are but only in terms of degree. The labor market still ultimately pays the final costs for what are monetary errors. It is still paying. The day after Labor Day here in the United States, though Economists pay them no mind we might notice copper, gold, and a re-rising dollar – the very thing that changed in 2008.

Stay In Touch