In yesterday’s post on the price of gold and its direct relation to collateralized liquidity I linked the shortage of collateral to QE. For the sake of space I omitted the demand for liquidity part of the equation. This post aims to fill in that variable, particularly in the context of the gold price shamble.

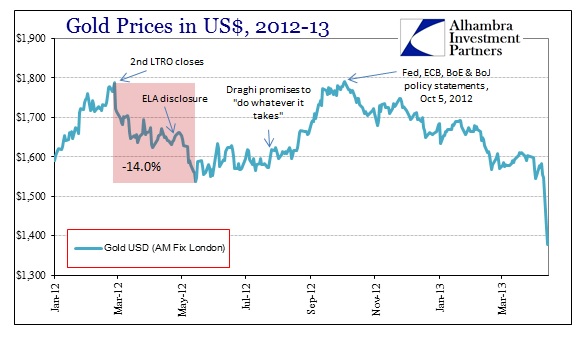

We should not forget that gold sold off in 2012 as well. From the moment the second LTRO closed through the beginning stages of the Spanish end of the sovereign crisis, it follows that there would be a collateral shortage in euros. Not only did the LTRO’s require collateral postings (that further drained the system) but the Swiss National Bank (SNB) during those months had been converting its burgeoning holdings of euro currency to “good” Eurozone sovereign debt. That linked the negative interest rates we saw in Switzerland with German sovereign yields – the SNB transformed euro inflows into Switzerland into holding German bunds.

In terms of collateral, it removed usable securities from the European pool at an inopportune moment. So gold sold off by 14%, again in anticipation of further banking and asset problems.

Now, as far as the current selloff goes, the most recent high was reached October 5, 2012. That day saw a convergence of central bank meetings and policy statements. At the ECB, Draghi re-iterated his stance (from July 26) to protect the euro at all costs. The Bank of England re-affirmed their stance on QE and signaled a willingness to go beyond the program’s scheduled end.

In the United States, Fed minutes hinted at preferences for easing beyond even QE 3 into unlimited purchases of US Treasuries,

“Members generally judged that without additional policy accommodation, economic growth might not be strong enough to generate sustained improvement in labor market conditions.”

Finally, in Japan, Economic and Fiscal Policy Minister Seiji Maehara urged the Bank of Japan to conduct “powerful” monetary easing, including the purchase of foreign bonds.

Yet, despite all these signals from central banks toward a determined preference for debasement, gold began to selloff. Perhaps gold investors expected more out of central bankers and were “disappointed”, but I don’t think that is enough of an explanation for the consistent downward trend in gold prices since that day.

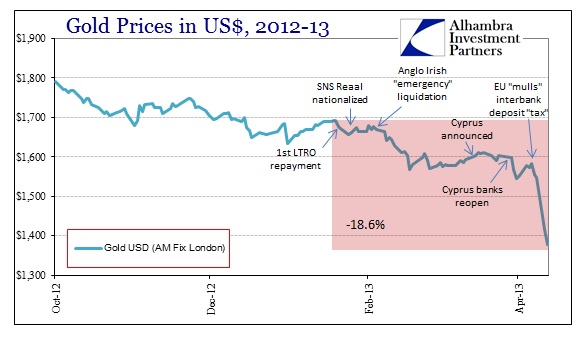

As we moved into 2013, the conventional narrative seems to be that Europe was into the clear until Cyprus. Fears over Cyprus as a “template” for resolving further banking dysfunction have cracked the façade of “the crisis is behind us” rhetoric. However, Cyprus was not the first crack, it was actually the third in succession.

On February 1, the Dutch government announced that SNS Reaal was being nationalized in a €3.7 billion bailout. The term “bailout” is somewhat misleading, at least as it applies here. The SNS nationalization broke with recent trends in that both shareholders and junior creditors were wiped out immediately. Total losses to subordinated creditors were estimated at €1 billion, an indication that governments may have reached “bailout” limitations.

Only a week later, the Irish Parliament met in a midnight session to approve the liquidation of Anglo Irish Bank (under a new name, IRBC). It was an extremely unusual move, but necessitated, according to Irish government officials, by a leak of Irish plans to the press. The Irish government and the Irish central bank had been negotiating with the ECB over extinguishing/converting Promissory Notes the Irish government had pledged in order to obtain ECB/ELA funding for Anglo Irish.

Irish Finance Minister Michael Noonan stated that it was necessary to take, “immediate action to secure the stability of the bank and the value of its assets, valued at 12 billion euros (£10.4bn), on behalf of the state.” What Minister Noonan did not say, and did not disclose until later, was that depositors would be subject to the now-infamous €100,000 ceiling on deposit insurance.

Testifying to the Irish parliament on February 13, Noonan noted that there were €323 million in deposits on record as of the end of January (likely time deposits that had yet expired), and that only about €200 million were covered under deposit insurance. Of the €123 million remaining, only €30 million would be reimbursed, leaving depositor losses at about €93 million.

Bondholder losses, however, were attached to certain classes. Some senior holders were to take 25% losses on their holdings, getting reimbursed by the ELG for €750 million of a reported €1 billion in positions; while €200 million in junior debt would be wiped out completely.

In effect, then, the Anglo Irish experience would set the table for Cyprus. In close proximity to SNS, I think bondholders (and perhaps some depositors, as evidenced by the movement of deposits out of Cyprus in the weeks before March 15) began to see the writing on the wall. These nominal amounts are tiny in comparison to banking markets and funding regimes all over Europe, but it isn’t the size that is worrisome it is the growing use of the same “template” – the entire character of bank bailouts appears to have changed. European governments were talking about “bail-ins” and haircuts in Spain the year before, but are now practicing them in Holland, Ireland and Cyprus.

In the context of bank liquidity, gold prices hit a high just before the first LTRO repayment in January, and then sold off hard after Anglo Irish. There was a period of calm before Cyprus, but again another selloff the day Cypriot banks reopened from their government imposed “holiday”.

However, as is clear by the chart above, the heaviest selling in gold started April 11. On April 10, it was reported that European finance ministers were to consider a proposal to extend depositor haircuts to interbank deposits. According to Reuters, the provision was to be included for any interbank deposits of less than one-month duration.

“While it is acknowledged that bailing in interbank liabilities may carry certain risks,” officials write in the document, seen by Reuters, “on balance, it is preferable … that these liabilities are not excluded from bail-in”.

If this overall interpretation of angst in European funding markets is correct, then the cumulative effect of everything from SNS to Anglo Irish to Cyprus to the EU memo is potentially a large shuffling of funding, particularly for banks that are perceived to be the weakest. Not wishing to be a liability holder in the crosshairs of bail-ins and deposit haircuts, counterparties to these weak institutions may have removed themselves in full or in part (to get below the €100,000 insured limitation for individuals). In turn, that may have forced these firms to find funding substitutions at short notice, eventually appealing to whatever collateral relationships they could find including gold-based.

I have little doubt that this kind of pressure on gold was cascaded into other selling pressures, including running preset stops. However, I do think the impetus for selling, particularly in the wake of continued and unprecedented central bank debasement activities, is a window into interbank liquidity problems. If we add in the collateral actions of various QE’s, the pieces connect here all too well for this to be ignored.

Stay In Touch