That there was no change to QE was not really unexpected in October, though consensus about this kind of policymaking theater has become somewhat of a crapshoot. The reason is, contrary to pre-crisis experience, a growing and more obvious schism in the FOMC façade. There have been disagreements in the past, uncovered by the delayed release of full meeting transcripts, but they never seemed as deeply philosophical as they are now.

On the one side includes several FOMC members, particularly DC Board member Jeremy Stein. Appointed in May 2012, the former Harvard professor and Obama Administration member seems to have been at the forefront of the clique that advocated caution over asset prices. He noted in February 2013 that he was concerned about “overheating credit markets”, particularly in certain mortgage segments and high yield.

“The first stop on the tour is the market for leveraged finance, encompassing both the public junk bond market and the syndicated leveraged loan market. As can be seen in exhibit 2, issuance in both of these markets has been very robust of late, with junk bond issuance setting a new record in 2012… On the one hand, credit spreads, though they have tightened in recent months, remain moderate by historical standards. For example, as exhibit 3 shows, the spread on nonfinancial junk bonds, currently at about 400 basis points, is just above the median of the pre-financial-crisis distribution, which would seem to imply that pricing is not particularly aggressive.

“On the other hand, the high-yield share for 2012 was above its historical average, suggesting–based on the results of Greenwood and Hanson–a somewhat more pessimistic picture of prospective credit returns.16 This notion is supported by recent trends in the sorts of nonprice terms I discussed earlier (exhibit 4). The annualized rates of PIK bond issuance and of covenant-lite loan issuance in the fourth quarter of 2012 were comparable to highs from 2007. The past year also saw a new record in the use of loan proceeds for dividend recapitalizations, which represents a case in which bondholders move further to the back of the line while stockholders–often private equity firms–cash out.”

He called this cumulative behavior “reaching for yield”, which is exactly what has been warned for years going back to the original ZIRP. In some sense it is a contradiction because the Fed intended for this happen, though not to this degree (I assume, at least for some of them).

But that wasn’t the end of it either, as Governor Stein went further along the “reach for yield” thesis and right into repo financing and systemic liquidity. It was “collateral transformation” that was really driving concerns over potential risk.

“Collateral transformation is best explained with an example. Imagine an insurance company that wants to engage in a derivatives transaction. To do so, it is required to post collateral with a clearinghouse, and, because the clearinghouse has high standards, the collateral must be ‘pristine’–that is, it has to be in the form of Treasury securities. However, the insurance company doesn’t have any unencumbered Treasury securities available–all it has in unencumbered form are some junk bonds. Here is where the collateral swap comes in. The insurance company might approach a broker-dealer and engage in what is effectively a two-way repo transaction, whereby it gives the dealer its junk bonds as collateral, borrows the Treasury securities, and agrees to unwind the transaction at some point in the future. Now the insurance company can go ahead and pledge the borrowed Treasury securities as collateral for its derivatives trade.

“Of course, the dealer may not have the spare Treasury securities on hand, and so, to obtain them, it may have to engage in the mirror-image transaction with a third party that does–say, a pension fund. Thus, the dealer would, in a second leg, use the junk bonds as collateral to borrow Treasury securities from the pension fund. And why would the pension fund see this transaction as beneficial? Tying back to the theme of reaching for yield, perhaps it is looking to goose its reported returns with the securities-lending income without changing the holdings it reports on its balance sheet.”

We saw exactly this kind of behavior in the housing bubble. Apart from the “reach for yield” in the mortgage space through securitizations, several of the now-notorious Wall Street firms engaged in the collateral transformation business as well as other more “risky” transactions that ultimately proved disastrous. AIG was a perfect example.

So it is not necessarily the search for returns that is problematic, but the systemic and ultimately endemic behavior it engenders. All the while, such risk is so deeply embedded that it never gets appreciated outside of cursory reviews like Fed speeches or even investigations. I think this argument was persuasive enough to at least temporarily commit the Chairman, Bernanke himself, to begin thinking and talking about “taper.”

On the other side sat not necessarily the ultra-doves like Eric Rosengren (Boston Fed), who at least tried to formulate (badly) cover for taper despite being formerly and squarely in the QE-forever faction, but the “deflationists” like James Bullard (St. Louis Fed). Bullard’s first (and it seems, only) priority is disinflationary conditions and anchoring behavior. He warned all the way back at the June FOMC meeting, during the height of the bond selloff, that, “the Committee should have more strongly signaled its willingness to defend its inflation target of 2 percent in light of recent low inflation readings.”

And so it seemed as if the “risky behavior” camp squared off against the “deflationists”, with taper in control, until the summer turned decisively in favor of the latter despite little respite for the former’s concerns. Inflation has been consistently below target, and that is a bigger problem for the FOMC than “risky” behavior or asset bubbles (in their orthodox views).

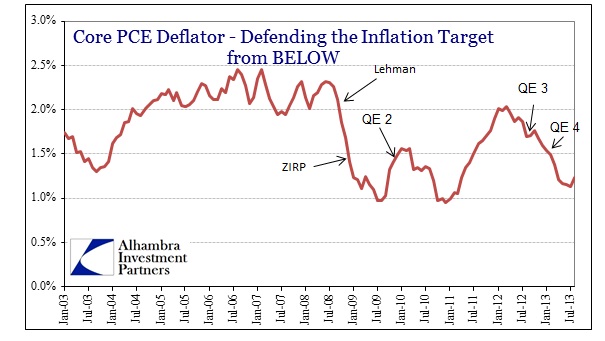

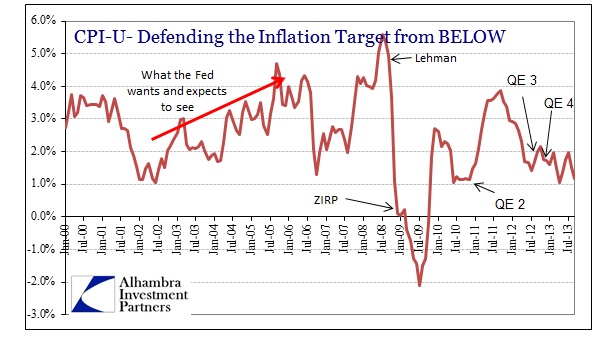

Concurrent with today’s FOMC meeting, the latest CPI release for September shows much the same pattern/problem, previewing further readings on inflation – including the “core” PCE deflator. Inflation, in the official measurements and estimations, is not (and has not) responding to QE at all. In turn, neither is the real economy, as the two go hand in hand (owing to the expenditure approach to the Laspeyres method of the CPI).

Without devolving into a critique of the entire idea of inflation measuring, the official inflation statistics will likely be interpreted as a potential change in inflation anchor. The implementation of ZIRP all the way back in December 2008 forced the Fed to the infamous and loathed (from Japanese experience) Zero Lower Bound (ZLB). Once there, the only policy prescription in the orthodox framework was negative real interest rates, accomplished only via psychology on market inflation expectations.

The CPI track above shows that it seemingly “worked” with QE 2, but only too well. The upward move in commodity prices, not matched by wages (in common with Japan) led not to a virtual cycle of a full recovery as expected (and what we saw, though artificial, in the housing bubble) but a retrenchment by businesses and consumers. Instead of hiring, companies redoubled their efforts to manage costs.

So rather than “anchoring” inflation expectations above or close to the 2% inflation target as the FOMC expected from QE 2, inflation expectations seemed to have moved lower again. The appeal to additional QE in September 2012 was likely an attempt to arrest that dynamic and try to kickstart what began with QE 2 in 2010.

Now with a full year of new QE, that official inflation has not rerun the 2010-11 experience has to be very troubling to the FOMC, as that would more than suggest inflation expectations anchoring into disinflation. That would be the nightmare scenario – disinflationary expectations against a sagging economic backdrop that may feature intermittent dollar tightening. That inflation has not responded to either QE 3 or QE 4 offers a great deal of confirmation for this interpretation, particularly since it was the direct opposite of the QE 2 period.

Yet, we still have the Stein problems and at larger and larger scales. And so the FOMC has led markets and the economy into the trap. Tapering leads to tightening and thus the dreaded deflation potential, while not tapering continues and even bolsters the “risky” and potentially dangerous behavior and asset bubbles – LOSE, LOSE.

Click here to sign up for our free weekly e-newsletter.

“Wealth preservation and accumulation through thoughtful investing.”

For information on Alhambra Investment Partners’ money management services and global portfolio approach to capital preservation, contact us at: jhudak@4kb.d43.myftpupload.com

Stay In Touch