Analyzing anything of and around China is difficult to begin with, so any misconceptions that form are understandable. That being said, there are certain methodologies to global finance that penetrate even these potential bends in conventional wisdom. I think that applies to recent commentary on the Chinese financial system as it relates to currency changes.

After appreciating steadily since revaluation in 2005, the yuan has taken a violent turn toward devaluation. That is conspicuous not only for the sharp inflection in trend, but also the timing as it relates to financial system difficulties. It would seem to suggest a causative relation, though correlation is never to be taken with certainty for causation.

Caveats aside, the mainstream analysis of Chinese yuan depreciation typically takes the form of “hot money.” In other words, the PBOC doesn’t like “hot money”, which is built on the predicate assumption of a durably rising yuan, and so has engineered a devaluation to “punish” these speculators.

It’s a logical theory in that very narrow analytical corridor, but it leaves far too many unanswered questions and unsolved causal chains. Why now, for example? What has suddenly changed about the PBOC’s attitude toward “hot money?” What underscores the vulnerability of this theory is the idea that the PBOC is the only factor driving currency, as if it was in total and absolute control.

Further, convention assumes that devaluation is tied to “capital flows.” In the Wall Street Journal this week, this assumption was asserted as,

The only thing that could really undermine China’s currency in the long term is capital moving out of the country. The government has strict controls on that, with residents limited to taking $50,000 abroad–plenty for shopping trips to London, but peanuts in the world of international financial flows.

That would be true if you completely ignored global finance, which the author confusingly refers to in that last clause. There is a surefire path to devaluation that does not involve “capital” (really currency, not true capital), something that emerging markets became very familiar with starting in May 2013.

A second Wall Street Journal article comes much closer to that idea, though unfortunately parroting the official stance on the currency markets.

“There is no basis for big appreciation of the renminbi,” the PBOC said, noting that China’s trade surplus now represents only 2.1% of its gross domestic product. At the same time, “there is no basis for big depreciation of renminbi,” the central bank added, saying that risks in China’s financial system are “under control” and the country’s big foreign-exchange reserves can serve as a big buffer against any external shocks.

What was the PBOC going to say, that they are experiencing desperate problems with dollar liquidity? They are going to proclaim, as all central banks do despite every evidence to the contrary, that they have everything under control, screaming like Kevin Bacon’s character in Animal House that “all is well” even as evident chaos descends.

In that second Wall Street Journal article I referenced above, the answer is revealed but detached completely from what I believe is true causation.

The band-widening announcement came as China’s central bank in recent weeks has engineered a decline in the yuan’s value to drive out speculators betting on the yuan’s continued rise and to introduce greater two-way volatility into its trading, in a bid to pave the way for expanding the band. The PBOC has done so by guiding the parity rate lower and by instructing big state-owned Chinese banks to aggressively purchase dollars.

In the Journal’s formulation, the PBOC is directing affairs, sending out “instructions” that Chinese banks should “aggressively purchase dollars” ostensibly to punish those hot money speculators. Given what we know of copper and dollar financing in general, is that really the case? Is it not more likely that the PBOC has lost control of dollar conditions and was forced by the “market” to widen the daily band in order for dollar-starved banks to aggressively bid for dollars they could not otherwise obtain?

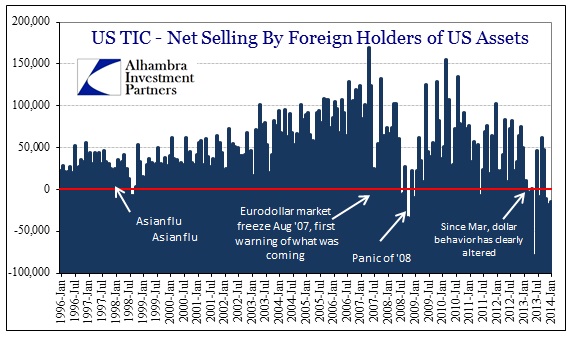

The former theory presented by the Journal, and echoed across the mainstream, is based solely on the convention that the PBOC is omniscient. My latter theory is backed by conditions in copper and elsewhere. The TIC data, for instance, while being several months in arrears provides a useful overview of global dollar conditions. What we have seen since May of last year shows fits of desperation in not only foreign central banks (Brazil) but private dollar participants as well.

After a massive dollar warning in June, total net selling of all US assets by both official and private counterparties waned in September and October. But by November, continuing through the latest data for January 2014, dollar selling was back. You can see in the chart above just how rare net dollar selling is in the history of the past two decades. Further, the timing of net dollar selling coincides exactly with periods of extreme dollar stress – net selling of dollar assets is solely related to dollar liquidity in various global locations.

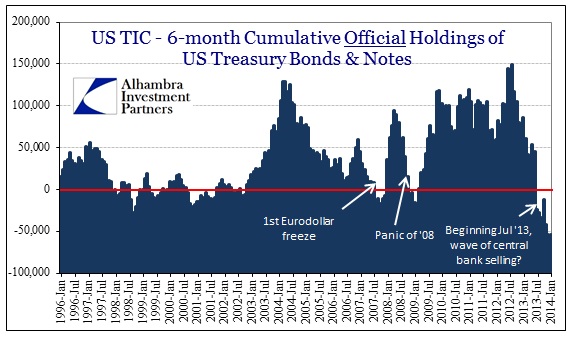

The main “reserve” asset, to which the PBOC was referring in the WSJ quote above, is US Treasury securities. When we see central banks’(“official” holders) levels of UST’s decline it is a very safe assumption that those central banks are desperately trying to obtain dollar liquidity to open an alternate channel for their local and domestic financial systems. A full part of that desperation is the Federal Reserve’s extreme reticence to open direct dollar swap lines with any central bank outside the G-7 or G-10 framework. That helps us pin down the geography of these dollar problems.

What all this data shows, as opposed to conjecture about the supernatural powers of central banks, is that yuan’s devaluation may be directly tied to dollar shortages. In fact, as I argue here, it is far more plausible that a dollar shortage (showing up as a rising dollar, or depreciating yuan) is forcing the PBOC to allow a wider band in order that Chinese banks can more “aggressively” obtain dollars they desperately need. Worse than that, the PBOC itself cannot meet that need with its own “reserve” actions without further upsetting the entire fragile system.

That is a rather stark contrast to what convention says of both China and central banking. But it does conform, and strongly so, to the data we have on hand.

Click here to sign up for our free weekly e-newsletter.

“Wealth preservation and accumulation through thoughtful investing.”

For information on Alhambra Investment Partners’ money management services and global portfolio approach to capital preservation, contact us at: jhudak@4kb.d43.myftpupload.com

Stay In Touch