The FOMC continues to posture as if the economy is good enough to allow the first “tightening” in policy since Alan Greenspan. If we have learned anything from the era of shadow finance and the global eurodollar standard, it is that in these unsettled times the true “money supply” of bank balance sheet mechanics behaves of its own accord. In fact, if you go back and review that last monetary shift especially in 2005 and 2006, credit markets were fully unperturbed by the sustained increase in the federal funds target.

Once the crisis came in 2007, the positions flipped whereby the FOMC began to “loosen” while funding markets again paid no mind and instead continued to “tighten” so much that it went right on into full and outright panic.

We are not quite at that kind of situation just yet, but there is still a lot about credit markets that do not adhere to the FOMC’s vision of what is transpiring. While the FOMC continues to talk about “tightening”, funding markets have already done so in laborious fashion producing a few notable “events” along the way. Yesterday’s SNB decision was simply another in the growing string of warnings about “dollar” positioning.

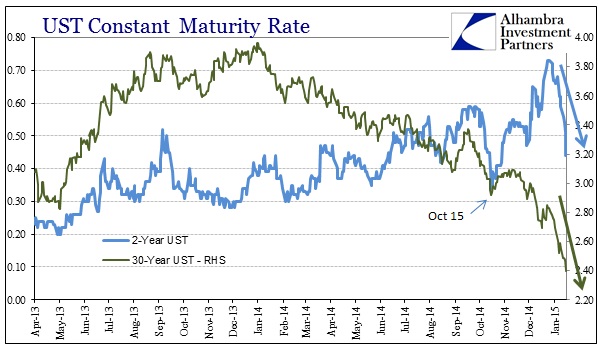

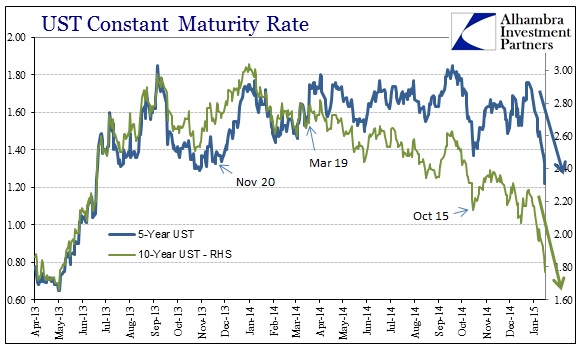

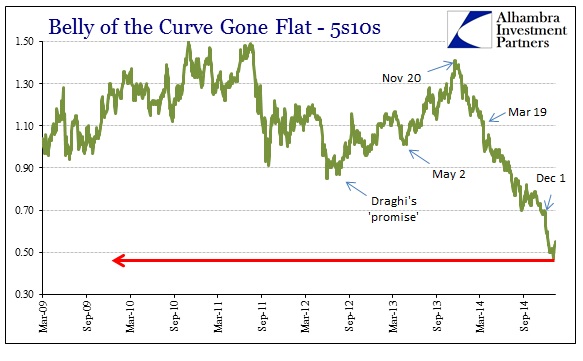

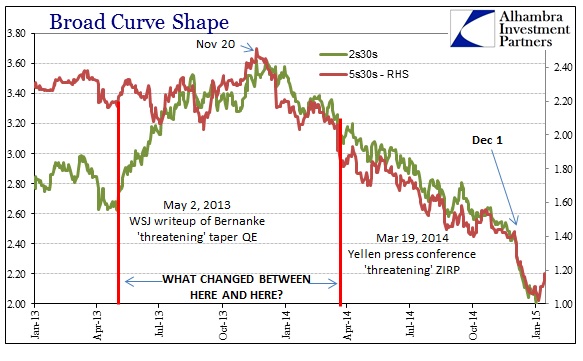

The bearishness in the shape of the UST yield curve prior to this month could have been characterized as growing belief that the FOMC’s exit strategy was destined to no good end. That was almost the whole of the flattening, as near-term rates, particularly the 2-year, actually rose slightly throughout while the longer end was especially bid (with amplification after December 1). So there was conviction on both ends, that the FOMC will actually do it and the probability of that being a “soft landing” diminishing by the month. Credit and funding vs. economists.

What’s remarkable about January (and some of December, see below) is that there seems to be far less belief that the FOMC will actually get there – or if they get to raising short-term rates that they won’t be able to go very far with them. The collapse in the 2-year nominal yield (above) is the largest move in years, now slightly more “doubtful” than even the bid for safety (and collateral) into October 15. Just yesterday alone, the 2-year yield dropped 7 bps to 0.44%.

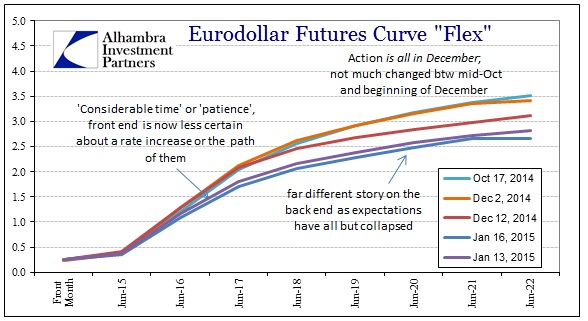

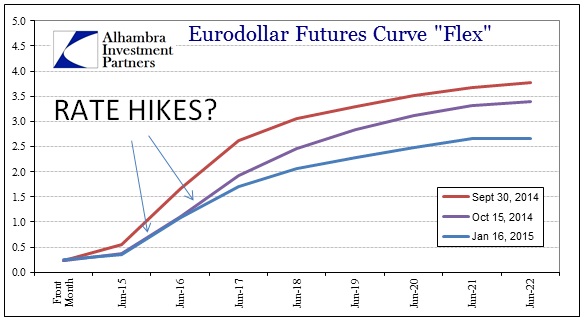

That is exactly what is being traded in eurodollars as well. The eurodollar futures curve since the start of December looks increasingly doubtful about the supposed end to ZIRP, while at the same time flattening in the outer years as if there is no good to come of any of it either way.

In fact, the near-term maturities on the futures curve are now as pessimistic about the FOMC’s bias as they were on October 15 when all hell was breaking loose – which seems appropriate as the SNB decision is actually quite equivalent in that respect.

In fact, you have to go all the way back to May 15, 2013, just as the taper selloff was gaining strength, to find a narrower calendar spread in the 2015-2017 period, exactly this “policy window.” The difference across those eighteen months is obvious, as there is no more QE to “explain” why yields and curves would be so narrow and flat. In other words, credit and funding markets are moving all their own decidedly against the recovery and “normalcy” pathway the FOMC insists is more than just statistical imagination.

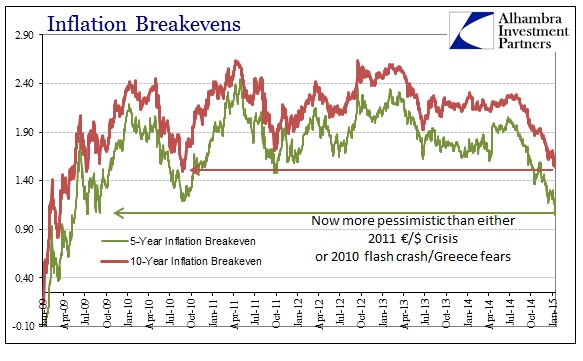

The constant reference to future wage growth has simply fallen on deaf credit ears. In terms of inflation expectations, the repeated promise of wage growth seemingly added some pause to the act even though wider credit was already moving against the narrative, but that ended when the “dollar” began to rise (tighten). There is nothing left to suggest wage growth is imminent or even possible at this point – a position to which credit is increasingly convinced.

Even the Fed’s preferred inflation metric, the 5-year/5-year forward rate has moved so far in the “wrong” direction that it is as “disinflationary” as the worst days of the 2011 crisis breakout.

The net result of the decline in nominal yields all across the treasury curve has been a slight steepening, but that only shows just how far the shorter-terms have reversed against the end of ZIRP.

It is sublimely odd that the central bank in Switzerland would trigger such increasing doubts about the abilities to act of the central bank in the United States. Then again, global “dollar” disruption is exactly that.

Stay In Touch