The Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, Janet Yellen’s old institution, has made a habit of breaking with orthodox trends and actually citing and disclosing deficiencies in economic study. In its latest effort, the bank channels a bit of Stanley Fischer and states the obvious, or what everyone else has known for a long time:

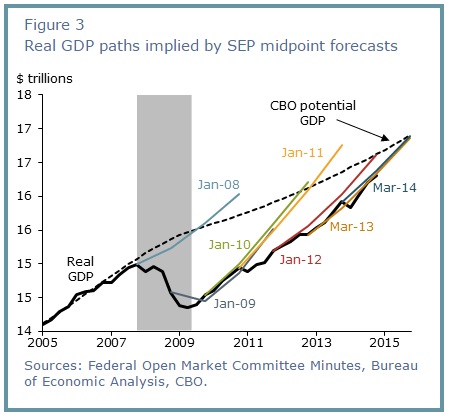

Over the past seven years, many growth forecasts, including the SEP’s [Summary of Economic Projections] central tendency midpoint, have been too optimistic. In particular, the SEP midpoint forecast (1) did not anticipate the Great Recession that started in December 2007, (2) underestimated the severity of the downturn once it began, and (3) consistently overpredicted the speed of the recovery that started in June 2009.

The timing of such a statement is almost too perfect, as if there were some turf war being waged within the bowels of the academic apparatus supporting the FOMC’s policymaking efforts. As you may have heard, the FOMC and its SEP has made another set of very rosy projections upon which they want the whole world to believe they will be adjusting policy. It seems at least a bit odd for FRBSF to release a study right now detailing how the Fed’s economists have been too overly and consistently sanguine going back to at least 2007.

Further, the main emphasis about the implications of all this relate to monetary policy itself. Perhaps this is, like Bernanke’s final year, an attempt to get Congress and the fiscal side to “do something” as monetary policy just isn’t effective, or at least as much as the models have been projecting.

According to the SEP, “each participant’s projections are based on his or her assessment of appropriate monetary policy.” A possible explanation for the SEP’s prediction of a rapid catch-up to potential GDP after 2009 is that participants overestimated the efficacy of monetary policy in the aftermath of a so-called balance-sheet recession…The SEP’s overprediction of the speed of the recovery could also be linked to other factors. These include possibly underestimating the damage to the economy’s supply side, as evidenced by the downward revisions to potential GDP, or perhaps expecting larger effects from stimulative federal fiscal policy.

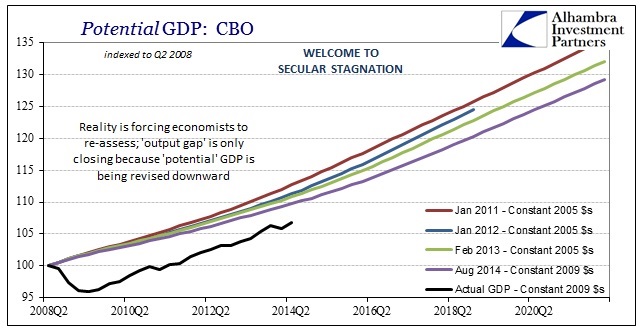

The mention of the “damage to the supply side” is extremely important, because it relates directly to actual economic potential; as opposed to the orthodox approach of using some “updated” Phillips Curve methodology of some calculation of full employment consistent with the inflation mandate. This is a process that has led to statistical revisions in the “potential” of the US economy, especially as modeled by the CBO.

This is something that I covered back in November, using the same CBO figures but presented slightly differently for emphasis.

At the time, I wrote:

So when the implied growth rates are downgraded in that “normalization” to early 2017 (when the output gap is supposed to be closed no matter what), what the CBO is really doing is reducing their estimates of “potential” to what should be an alarming degree. That is the only way to “close” the output gap, and quite contrary to all prior experience where the output gap is closed by the simple act of actual economic growth. [emphasis in original]

That is an important point that cannot be overstated. Every single recovery in the historical record followed that pattern, set out in Milton Friedman’s “plucking model”, and the current one not only fails to do so but in spectacular underperformance. There can be no denying that something is not just amiss but devastatingly so. Now even the Federal Reserve, at least in its San Francisco operation, has begun the process of downgrading not just QE but all of monetarism!

This is consistent with the idea of secular stagnation, but inconsistent with the current academic thinking about its cause – that the economy itself is somehow deficient. One need only connect two dots here, but that is still too far for even those predisposed toward some degree of objectivity free of orthodox bias.

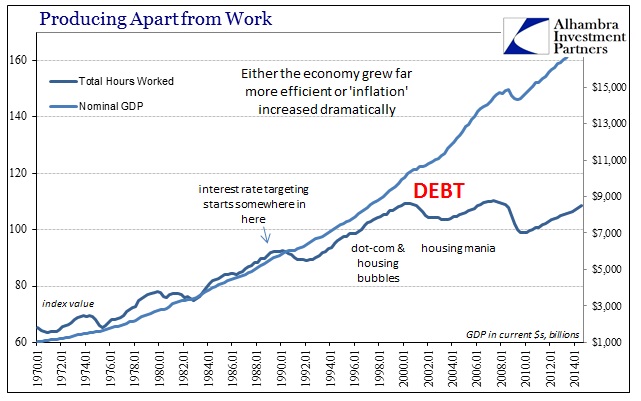

Part of that relates to the orthodox treatment of monetary neutrality, given that they believe, somehow, that monetarism bears no long-term impacts upon either the economy or its potential. The more the economy fails to live to its academic model of potential, the more trouble monetary neutrality runs, especially since the uniting factor in this “recovery” cycle is the heavy-handed presence of monetarism itself. It is hard to say that the economy has suddenly attained a mysterious structural deficiency when all forms of obvious structural deficiencies are consistent with intrusive redistribution.

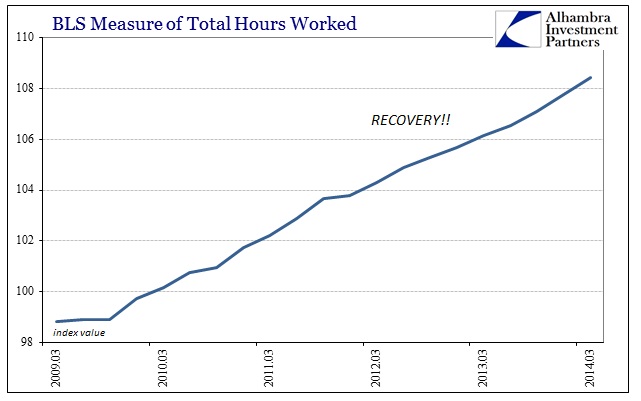

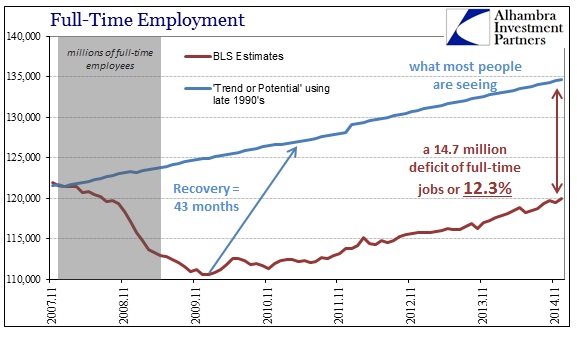

Some of this is very basic, as in what the mainstream actually thinks constitutes “the economy.” This gets back to something I highlighted recently, namely the very striking difference between GDP growth and the labor market. Economists take GDP literally when its divergence from labor suggests at the very least some high degree of caution in doing so. It would stand to reason that any “supply side” defects might be consistent with the lack of labor utilization no matter how high GDP runs independently.

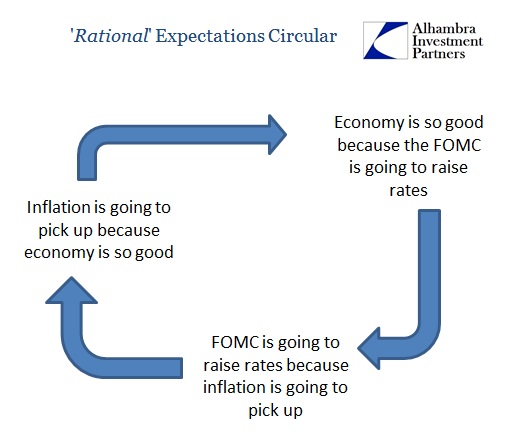

The FRBSF paper identifies part of the problem in its assertion of “rational expectations”, at least as it relates to forecasting and modeling:

Research has identified numerous instances of persistent bias in the track records of professional forecasters. These findings apply not only to forecasts of growth, but also of inflation and unemployment (Coibion and Gorodnichencko 2012). Overall, the evidence raises doubts about the theory of “rational expectations.” This theory, which is the dominant paradigm in macroeconomics, assumes that peoples’ forecasts exhibit no systematic bias towards optimism or pessimism.

That does not consider how “rational expectations” theory may be taking a step further; that optimistic bias is not just a “mistake” of overconfidence, but rather intent about influencing current behavior. This is not just theories of inflation as it relates, supposedly, to monetary policy, as taken to a further extreme “rational expectations theory” could possibly influence all forms of economic activity. In other words, the FOMC is not being overly rosy solely because of mistakes in the models, but rather intentionally trying to get everyone to believe in the optimism so that it actually occurs.

This is also part of the theory contained within the modern command-economy approach exemplified by interest rate targeting (this is not dealt with in the FRBSF paper). Expectations form the basis of not just inflation, purportedly, but even recession itself. Some parts of the academic stream even go so far as to conflate recession fully with emotion. So the heavy lifting of something like QE is not even liquidity or the byproduct of bank “reserves”, but rather some New Age type of pop psychology about “good feelings.” That means the bias in the models is a positive feedback loop that self-reinforces its own narrative and its own conclusions – circular logic predominates.

Think about that in terms of something like the Great Recession and especially the Panic of 2008. The Fed, in its view of rational expectations, was systematically biased toward the most optimistic case – not just as in their own hopes but undoubtedly as a means to influence both financial and economic behavior. That is why Ben Bernanke in June of 2008 proclaimed very publicly that the “The risk that the economy has entered a substantial downturn appears to have diminished over the past month or so.” Anyone following that “command” was led like a lamb to the slaughter – such is redistribution which seeks, at its very basic level, for people to act in opposition to their own senses whether that makes intuitive sense or not.

Is it any wonder that the economy has failed to live up to prior inclinations of economic potential? The rationalization surrounding interest rate targeting in the first place was that, through manipulation of expectations, the central monetary authority could “fill in the troughs without shaving off the peaks.” Even attempting something like that means, again at the very basic core of economic function, you don’t believe there is any value in recession and creative destruction. That is a very much an accumulation of “supply side” factors.

As the economy continues to live down to its worst fears, the rest of the orthodoxy is having to catch up. But they will still, even though they readily admit their optimism is more often misplaced than not, attempt to call something a “recovery” that is clearly not. Maybe someday it will dawn that influencing behavior rather than allowing profitable resource allocation leads not to a “new normal” of perpetual growth and abundance but rather to its exact opposite.

Stay In Touch