Economics as a discipline has always fancied itself more of a hard science than a social science. That is why economists like to talk like physicists as if there is surety in the figures they use so publicly. It has even infected media coverage of economics, as the nomenclature about economists’ predictions has taken on an air of the definitive – reverence that is simply not matched by actual performance.

This is more than just Stanley Fischer’s assertion last year that economists have to apologize for their overly robust forecasts each and every year, or even the San Francisco Fed’s deeper look into forecasting bias off monetarism’s religious aspects, rather the calculation problems are symptoms of an entirely unrealistic appeal to precision. This is not something recent, as long ago economists, especially those like Simon Newcomb and John Stuart Mill that believed you could measure all “money”, fully expected to be able to quantify everything.

However, there is very little that gets done in a manner that is consistently logical. The most striking example is GDP’s inclusion of “owner imputed rent”, which is to say that the BEA estimates how much you as an owner and occupant of your house would pay yourself to rent out the “shelter.” No money changes hands and no actual transaction takes place, yet it is the single largest sub-component of PCE included in GDP; amounting to more than $1 trillion!

In the context of what ails the economy post-crisis, we have something of a similar problem as economists are desperate to find “lost” productivity. Productivity as a concept is vitally important as gains in true capital are the means by which living standards will rise in the future as they have so persistently risen in the past. The problem now is that such productivity has seemingly disappeared and economists are stumped.

Productivity is probably the most important measure of economic health that policy makers know the least about.

Its pace will help determine how soon Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen and her colleagues increase interest rates and how far rates ultimately will rise.

It’s a scary thought especially as those limitations don’t mean they won’t try to forecast it with something like precision:

John Fernald, a senior research adviser at the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, pegs the trend growth rate of productivity at 1.8 percent a year for U.S. businesses and 2.1 percent for the economy as a whole…

“There’s basically an 80 percent chance over the next 10 years that productivity growth will average between 1 and 3 percent,” the Fed official said.

While that sounds an awful lot like objective mathematics, there is so much subjectivity contained within that projection that it doesn’t even amount to a best guess. After all, it was the Federal Reserve that was so stumped by the change in assumed productivity after the end of the dot-com bubble – which they so far refuse to acknowledge played a role in their perceptions of productivity in the first place. In other words, I doubt they can even define productivity enough to actually attempt to measure it crudely, and certainly not accurately.

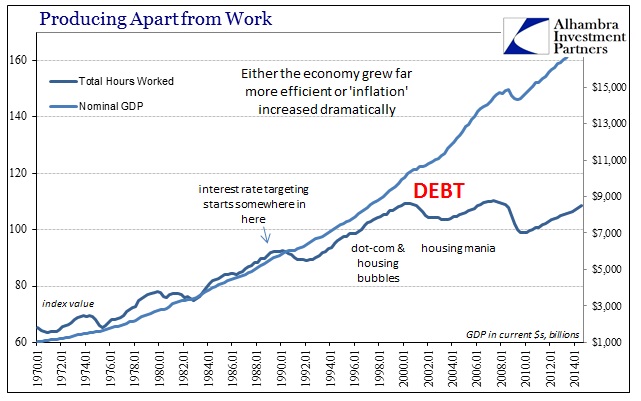

The way it is done currently is that it is not done directly. The BLS takes a stunted measure of real GDP and combines that with its own estimate of hours worked. The remainder between the two is assumed to be productivity, but if the BEA is off in its count of “inflation”, a major factor here, or the BLS over-estimates employment, then productivity isn’t productivity but a bad combination of bad mathematical inputs. In that case, the resulting numbers won’t make much sense; which I suspect is entirely the point here.

If there is a sickness about productivity in the US economy, it is not likely organic despite the current orthodox favor surrounding secular stagnation (which is founded in this productivity “mystery”).

Given the construction of the current thinking on productivity, perhaps it might be suggested that the increase in debt usage as a direct course of the asset bubbles were hiding “inflation.” The simplest explanation, rather than a mysterious and apparently unalterable advance in the productive nature of the US economy which somehow produced no benefits to US labor, may be that inflation has been “suppressed” during the period in which labor advancement has stagnated. That may not have been intentionally, but merely a byproduct of economic theory that doesn’t incorporate realistic complexity.

That passage speaks about the assumed rise in productivity during the dot-com era, which then led exactly nowhere in terms of labor utilization (as you can see of total hours worked in the chart above). That is not how productivity has functioned in the past, especially in the deep and beneficial transformations of the US economy from agrarian to industrial and now to “information.” In each of those processes, productivity gains freed up labor, making labor cheaper for other uses. That combined with innovation to lead to the very changes in labor composition that we see of the modern specialized economy, nothing like the extended dis-utility that we see of the current century; indeed, the economy was in relatively short order far better for those past transformations.

That has led so many economists to search for a cause in perhaps the end of innovation itself, as if mankind and American ingenuity are finite. Perhaps the solution is far, as usual, simpler but one which economists themselves can apparently see but never quite grasp:

Among the possible culprits: a surfeit of low-cost labor that’s encouraged companies to hire more workers rather than spend money improving the efficiency of existing staff through training or more up-to-date equipment.

I’m not at all assured that companies have been on such a hiring spree, in fact the opposite seems to be the case as employment has been entirely too slow to begin with – which would certainly indicate a problem with productivity as businesses aren’t especially enamored with adding to their biggest costs if there isn’t much gain from doing so (which includes the conspicuous problems with revenues). However, productive spending itself is almost certainly depressed, and likely historically so. Why might that be?

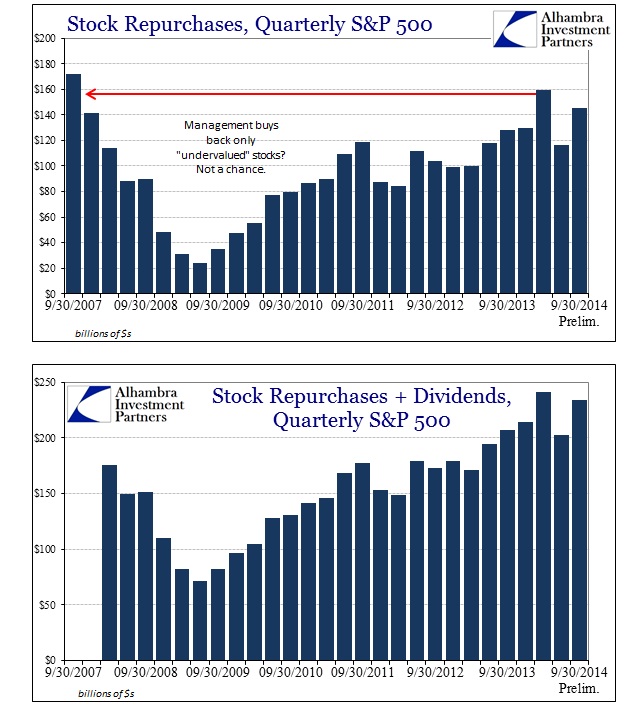

The problem about productivity seems far more conceptual, something that is prevented from gaining wider recognition because economists are far too busy trying to precisely measure it all. This would include the nefarious idea of monetary neutrality, to which the above insanity in stock repurchases would destroy if accepted. To preserve monetary neutrality means to search for a problem that may not exist, instead viewing the symptoms of the real problem as further obscurity toward even greater mathematical convolution. At the very least, there should be some multiplier for productivity added to account for how these economists expect to gain economic stability from interjected monetary instability, thus at least looking in that causative direction.

Stay In Touch