The issue of bank hoarding has become nearly mainstream as the size of the move into UST is now too large to ignore. It wasn’t so much an issue last year, apparently, as there was less to suggest taking very pessimistic portfolio allocations was anything other than an anomaly of regulation. This year the idea of prudence as opposed to blanket risk-taking is not so much seemingly illogical, to the point that banks, who continue to reiterate publicly the opposite of what they are doing privately, appear very prescient. It’s not just the price of oil and the collapse in Q1 GDP, the growing and undeniable “dollar” problem is now paramount to almost everything.

Toward the end of February even Bloomberg (h/t L Bower) had noticed that banks were into hoarding, though the story isn’t quite right about what and why.

Growth is on a tear, hiring is the strongest in decades and households are the most upbeat since 2011. Yet banks such as Bank of America Corp. keep plowing their burgeoning deposits into U.S. government and related debt — pushing the industry’s holdings past $2 trillion — instead of lending it all out.

Those two sentences are sublimely at odds with each other, or were in the context of Janet Yellen’s version of the economy. But even that $2 trillion figure is a little bit off, as just shy of 70% is allocated to agency MBS securities which are not highly liquid. The latest H.8 from the Federal Reserve reports $1.44 trillion in such securities as a subcomponent of the $2.09 trillion that Bloomberg was referring. The remainder, $653 billion, includes both pure UST and non-MBS agency debt, and that is where the massive growth has taken place. Those figures are not far off what the FDIC reported in its Quarterly Banking Profile.

Also consistent is the dramatic build in UST (UST + non-agency MBS in the H.8 version) dating back to the fourth quarter of 2013. Most mainstream commentary, when not fully and completely confused by this contradiction of economic convention, simply allows only that banks must be reacting to Basel or some such.

Part of the buildup has to do with rules that require banks to hold more high-quality assets in the wake of the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression. But it also reflects how borrowers, particularly among Americans scarred by the housing bust, are still repairing their finances rather than going into debt to splurge on big-ticket items. And that may mean the U.S. recovery isn’t quite as robust as all the upbeat data would suggest.

“Banks have so much cash,” said Peter Tchir, the New York-based head of macro strategy at Brean Capital. “Lending has loosened, but it is still just simpler for banks to own Treasuries.”

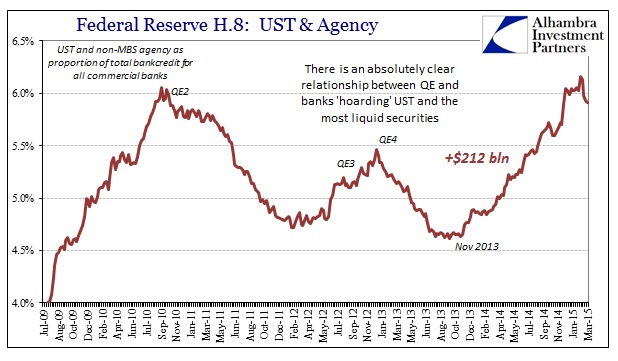

All that may sound simpler, but it doesn’t match the actual data. If you actually look at the proportional allocation of UST in bank holdings there is a clear relationship with the various QE’s. Banks begin their “hoarding”, the Fed does a QE and then they dishoard. You might make the case that is simply front-running in terms of buying to then flip to the Fed, scalping essentially rent, but the circumstances of those periods argue for liquidity concerns more than anything else.

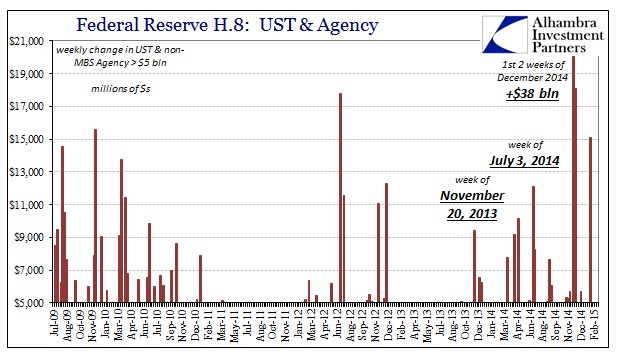

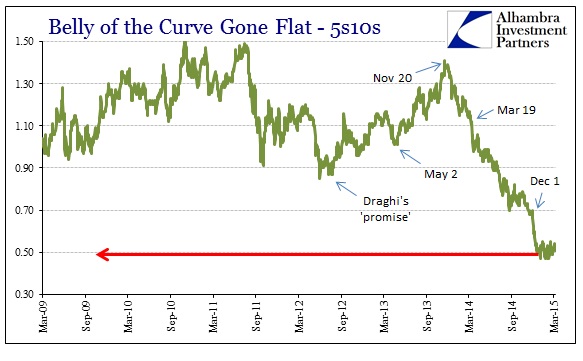

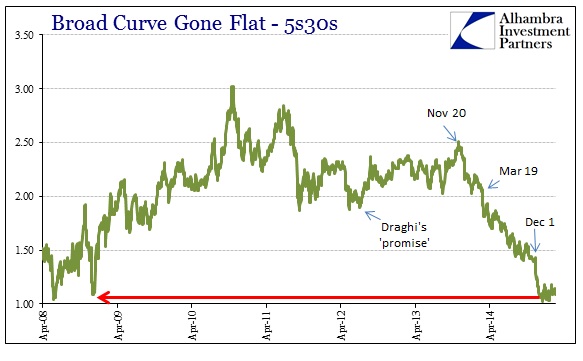

That is particularly true of this latest buildup. Clearly, banks were content to dishoard UST until around July 2013 – at the very bottom of the violent credit market selloff. That meant that the banking system had shifted to moderately adding to UST’s during the next few months. That slight increase in allocation changed suddenly and dramatically right at the week of (and this should be no surprise to anyone that has followed this research) November 20, 2013.

The link of that week to hoarding UST is not coincidence, as it represented a sea change in so many market indications. Again, we don’t have to wonder who is flattening the UST yield curve as the banks are doing that themselves. Further, other significant events line up with UST proportionality in bank portfolios – July 3, just after the repo market went crazy with huge fails surges; the 1st two weeks of December when credit market bearishness amplified across-the-board.

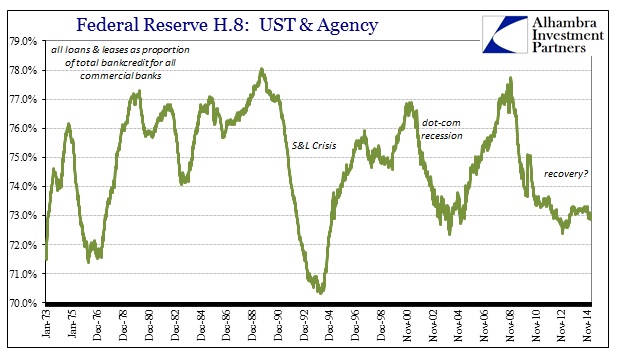

From that view, it is exceedingly difficult to attribute such behavior to regulation or the fact that “demand” for lending remains subdued. That has been the overarching trend in banking far a lot more than just the past few years. Even as loan growth has lingered at post-crisis lows, recessionary even, that does not itself lead to the conditions of UST allocations, and thus liquidity concerns, that are much more suited to generalized outlooks regarding expected volatility.

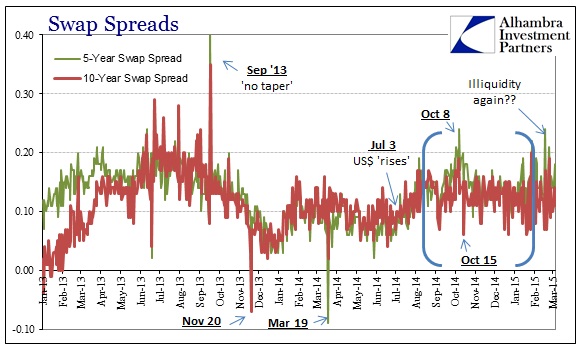

It is much more likely, given the clear patterns and relationships, that banks reacted to November 20, 2013, as a serious shift in just such an outlook. There are any number of indications that make that plain; the only problem, so far as the media and economists take it, is that none of those are favorable to the idea of a “booming” economy and “normalcy” in markets. The exact nature of what happened on November 20 remains a mystery, and may stay that way forever unless “someone talks”, but the implications do not need confirmation. I am convinced it was a major event in funding markets that nearly took out a huge chunk of dealer capacity – the indication being swap spreads and the relations of dealer positions, and thus collateral, surrounding that change in QE perception.

That whatever happened on November 20 ignited hoarding that has remained steep and active for almost a year and a half is not a signal that the world is headed in the right direction, the US economy first and foremost. With that headstart, there should be no surprise that less than a year after it began it ran into, and most certainly helped cause, a serious shift in global “dollar” markets. There really isn’t much mystery here, as it all adds up pretty well provided you aren’t completely captured by the wrong context. Liquidity is bad and getting worse and banks are preparing for that because, as the “dollar” indicates, the world increasingly looks headed for a dark place that doesn’t resemble anything of the mainstream narrative.

Stay In Touch