In the days before 2007, the idea of monetary “stimulus” was relatively straight-forward in theory as well as (seemingly) practice. A central bank declared that it would reduce an interest rate target and the “market” would respond by doing the work for it. In other words, all that was needed was an indication and banks would make it so as there was every reason to believe that a central bank would act should actual banks not. The threat was as credible as it was ever going to be because it had never been used; the cultivated cult of central bank power assured that.

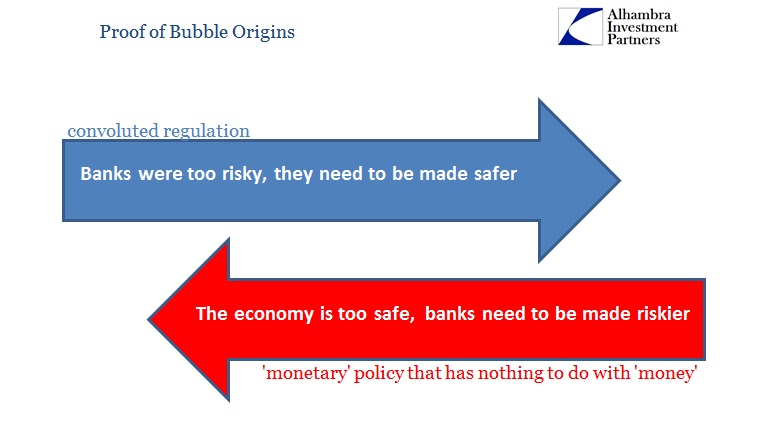

The closer financial systems got to the zero lower bound (ZLB), the more difficulties arose in both theory and practice. To go beyond the ZLB meant “unconventional” policies and programs where central bank abilities were not so widely shared in unquestioned belief. Among the limitations, so far, has been direct influence on actual credit in the actual economy. Liquidity concerns continue to plague these central planning aims, so the “best” that is left is a sort of measured extortion. In other words, central banks want banks to be highly liquid as a matter of not igniting the next crisis but at the same time want them to stop being highly liquid as a matter of restraining real economic growth (artificial) through loan devolution.

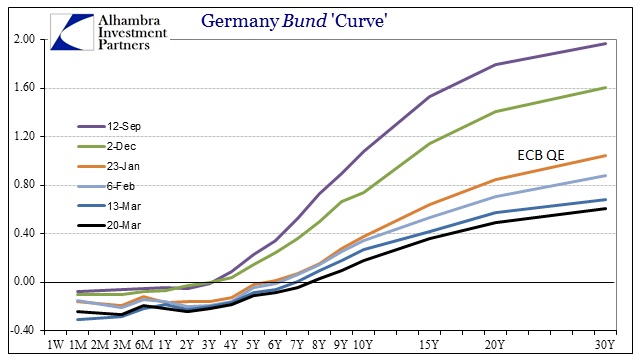

In Europe, the ECB’s response is highly revealing. With interest rates about as low as they can go (but not really), the true intent is not that but rather “portfolio effects.” In spite of requiring a liquidity buffer, the ECB is going to use QE, among its other “arrows” to borrow a phrase from Japan appropriately enough, to punish that very liquidity. By making it increasingly expensive, the intent is that banks will stop with all the government bonds, especially of Germany, and start lending to take advantage of what the ECB claims are robust spreads to private economy loans and securities.

In fact, in the press conference accompanying the ECB’s January announcement of its QE intentions, Mario Draghi was asked exactly this question of German bunds:

Question: First of all, how is it that buying bonds in Germany, where credit is not a huge problem, is going to translate into help for the credit-starved companies that we have in the so-called periphery of the eurozone?

Draghi: On the first question, this programme is meant to create a large injection of liquidity that is fungible across the euro area. So, if it starts in Germany, it can easily flow everywhere through our payment system. But certainly where the spreads are higher, you would expect greater effectiveness, greater immediate direct effects from this policy.

Translation: the ECB will “punish” everyone holding bunds until they can’t stand it anymore and go out on the “risk” curve. Because the spreads there are the greatest the ECB expects banks to go there most. Draghi gives no reason as to why this would be expected, only that it is taken as an absolute under monetary theory despite years now of all evidence to the contrary. In reality, banks have all manner of choices, including forgoing any such lending and taking advantage of the fact that the ECB has actually and instead constrained itself onto this same course of theoretical infinity.

The ECB is not alone, at all. The Federal Reserve underwent much the same in March 2008:

In other words, it may not be so certain who gets to decide what prices are “true” or “real” and which are to be discarded by subjectively, and often politically, determined exigent circumstances. Can the Fed simply vote that it doesn’t like the price of a stock or an entire class of fixed income “products” and thus act as if it has the only form of true knowledge? This opens the debate as to what market prices are and are for. If there is only to be “allowed” “normal” function, what happens when that mission becomes unto itself?

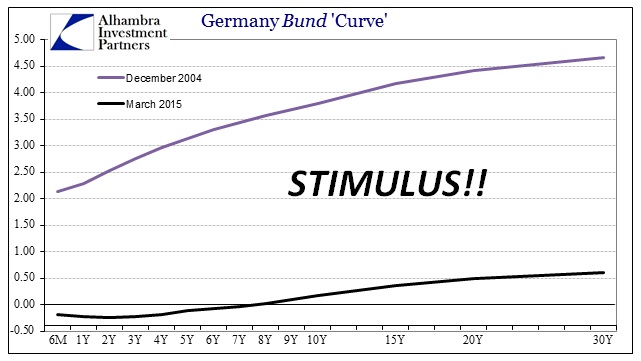

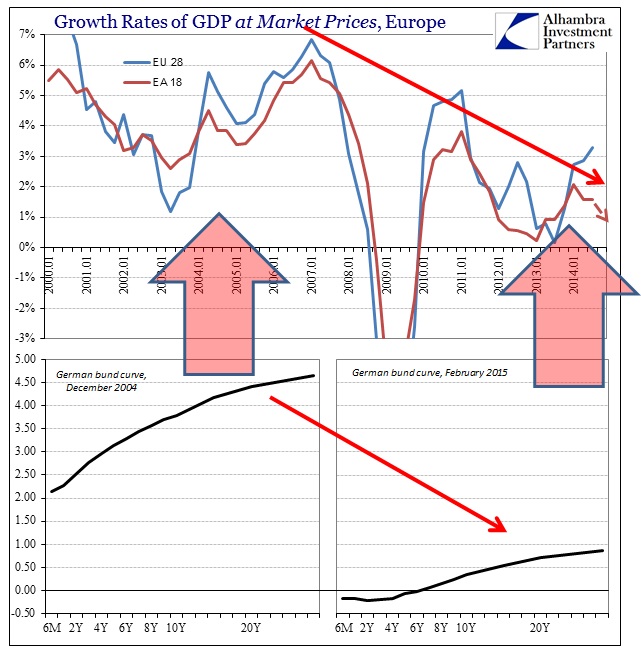

If the ECB, like the Fed, describes the economy of 2005 as “normal” and then dedicates its entire existence to achieving it, the “markets” have no place or certainly not any meaning outside of anything but a policy tool. Taken to an extreme, which I think we have entered if not far surpassed by now, this means that central banks will wreak havoc, financially slash and burn, until they get what they want. The results are easy to see:

The longer comparison, I think, shows this well in how the central bank in Europe is obviously intent upon destroying all time value of “money” (actually credit) in order to achieve a credit-driven recovery. If that makes sense to anything or anybody outside of orthodox monetarism I would be shocked, as it essentially means they must kill debt to make debt.

Using that perspective, the path that was opened by the alteration of policy limitations was not so much to seek a path back to normalcy but in the larger and more important sense to define bubble imbalances as normal. If the Fed sanctions great financial imbalance as a condition of its political view of how the world should work, then all things engaged to that end are thus deemed proper including the total overriding of all market determinations. Indeed, we know that without question by the Fed itself and its actions under QE and ZIRP; to re-establish and rebuild the economy as it was in 2005 as if that were anything like a good idea. What was established was the totalitarian-like framework where the FOMC deemed itself infallible and not subject to any falsification of any kind; a precarious self-appointment given that asset “markets” continually want to crash or revert to a less-chaotic or imbalanced state.

It simply becomes self-feeding and even self-referential; if financial agents realize that a central bank will do anything and everything to achieve their goal, why do anything else but cater to that feedback loop? Because they (the ECB in this case) are now locked into this strategy, it actually makes more sense for banks and financial firms to bet against it rather than the intended products of the strategy as a matter of actual market mechanics and the “necessary” incentives of the strategy itself; front-run by buying government bonds and producing failure because it will produce more opportunities to front-run government bonds. The only way that circle ends is if the ECB declares itself no longer interested in a credit-driven recovery, which is totally contrary to its very being.

The major component of any risk-taking in honest trade is time value, and it is the first factor to be obliterated in the name of forcing risk. There is a lot about orthodox monetarism that is upside down because of its preference for the mathematical equalities under general equilibrium; this is perhaps the worst of it, but goes a long way to explaining this:

This is not capitalism in even a resembling format, and these are not markets by any reasonable definition. Central bank interference, somewhat like the observer effect in physics, irretrievably alters the state of “markets”, especially in proportion to the pressure and intensity of that interference. Unlike the theory of monetary neutrality (another assumption to preserve equality of equations in general equilibrium) there are very real effects to all this.

Stay In Touch