When looking toward what might be coming next from the FOMC, the reigning theme remains “they don’t know what they are doing.” That sentiment applies, of course, retroactively to all the QE’s, Twists and badly implemented emergency measures on the way down, but attention is rightfully focused now on how to get to C. Going from A to B already, there remains a large transitive step to take and the Fed is hoping to do so as an almost reactionary program to go back to A. We know better.

This divergence starts with the plethora of “exit” tools that the Fed has amassed and even tested these past two years since they started toying with the idea. The fact that the indication of “taper” was released almost as soon as QE4 got under way says a lot about just how much affection the FOMC has for all their dangerous stunts and experiments. The problem, from their perspective, is that getting back to A requires even more experimentation. That itself should suggest that the ultimate destination is not a revisiting of A but rather an unguided mission into uncharted C.

The momentous heraldry with which the reverse repo program (RRP) was first introduced stands now in stark contrast to the almost-contempt with which the FOMC as early as last July now holds it – with good reason. Despite all the happy talk about “successful” tests, which somehow the standards for achieving that qualification are never released, the Fed at that July FOMC policy meeting made it clear that the RRP’s are an almost necessary-evil to them. That was one reason they were given a $300 billion daily cap back in September.

Participants generally agreed that the ON RRP facility should be only as large as needed for effective monetary policy implementation and should be phased out when it is no longer needed for that purpose.

In other words, the FOMC intends to do as little as possible before scrapping it entirely. Straight away, there are enormous problems with both parts of that summation. Nobody has any real idea what “large as needed” may account, and there is surely major debate to come about “no longer needed.” Taking the first part first, the FOMC originally decided on a relatively small RRP allotment, but has found out, under the qualification of “successful” testing mind you, that to achieve even their theoretical aims of raising rates in a conjunctive and orderly fashion would mean at least double the RRP’s.

More recent FOMC policy meetings have suggested that the academic economists have produced suitable regressions to that opinion, so much so that the FOMC has made it apparent that in all likelihood when the time comes (if it ever does) the RRP’s will likely come out totally uncapped. Writing now for Credit Suisse, by way of Perry Mehrling’s blog (thanks to R Burch for pointing it out), Zoltan Pozsar has placed the theoretical likelihood of the RRP’s on an exit above $1 trillion. As Mehrling points out, “that’s a pretty big disconnect” between what the Fed thinks on the affair and where more realistic assessments are heading.

Again, they don’t know what they are doing.

The issue of the RRP’s stands to connect these problems, from how big does it “need” to be in operation all the way to how long might it “need” to be around. The Fed has decided small and very, very temporary, but the reality of the money markets and the paradigm shift argue very much against that wishful thinking.

The problem is that money markets stopped working in 2008 without any actual replacement at hand (A to B). Dealers were primarily responsible for intermediating the structural inequities inherent in what is really an ad hoc global eurodollar system – it worked before because everyone thought it would. The reason that dealers played such a primary role was because they could pillage freely the financial system through prop trading and gain-on-sale accounting. There was too much profit (loosely defined in terms of GoS) in those to leave it alone, meaning that the eurodollar system on the way up was very much self-feeding and also the means by which it was all funded (certainly not boring and ancient deposits that ultimately limit financialism, and central bank activism).

The problem from A to B was that dealers got caught in the extremities of their own making, and instead of an orderly unwinding (which is never really a possibility) they simply exited. The Fed took far too long to come to terms with this paradigm shift, preferring instead to see the global banking system as it was in 1930 or at best 1960, which is why money market breakdown turned into broad and global panic (of banks, by banks). When it did finally act, what occurred was essentially the Fed remaking wholesale finance of its own balance sheet – not lender of last resort but market of last resort.

In the meantime, organic money markets have shriveled under the weight of this central bank intrusion. There are reasons of Dodd-Frank and Basel, but also of QE and profits.

The trouble, then, longer term is what comes next when the Fed no longer acts as that market of last resort; the money markets must shift back to being a private affair. The Fed, as noted above, wants to go back to A but dealer banks are essentially gone from money dealing and there isn’t any reason to expect that the end of ZIRP or QE will get them back into the habit – not without a total bypass of the Volcker Rule and conditions for renewal of “gain on sale” profits. That last part will be very difficult with fixed income prices in general expected to move in the “wrong” direction as part of all this.

As Merhling aptly points out, Pozsar too, as the central premise, this shift is not just off ZIRP and the eventual winding down of QE’s already undertaken but actually a character change, over time, of the entire complexion of the money markets in the US and globally. We went from A (dealer-led money markets) to B (central bank dead money markets) to a likely C of money market funds and other “cash pools.” Pozsar’s Exhibit 7 illustrates this evolution very well.

That will lead, in Poszar’s interpretation, to not only a minimum $1 trillion RRP but one that dismisses any idea of “no longer needed.”

Eventually, we expect a massive and permanent overnight RRP facility, with government only money funds emerging as the ultimate home of money dealing. Money market funds in many ways are anathema to central bankers. But to regain control over short-term interest rates they deal with them directly: the “marriage” of necessity will occur. [emphasis added]

There are also grave concerns about shifting to a money fund paradigm, as well. That would make the money system, if not global finance overall, much more like the shadow conduits that have been vilified (somewhat correctly) since 2007, and much less like the traditional and regulated banking system that everyone says they want. The focus of both Mehrling and Pozsar is about thinking ahead to what all that might look like, and that is a positive development in that someone beside those who don’t know what they are doing is actually and credibly pioneering what is really new territory.

My focus is and has been on the actual shift from B to C; after all, getting from A to B was an enormous near-catastrophe. Merhling puts together a synopsis of the money markets right now, and it is already divergent from the fantasyland inhabited by FOMC expectations:

This way of thinking may shed light also on the disconnect between the Fed interest forecast and the market interest forecast that we mentioned at the top. Possibly that difference is not so much about market expectations that the Fed will chicken out, and more about an expected increasing divergence between IOER and other money market rates. P&S Exhibit 4 shows plainly that the Fed’s RRP rate has provided a floor while IOER has provided a ceiling; Fed Funds effective has been in the middle. The market thinks that IOER can go up with no consequences for other money market rates. Even worse, the market thinks that there are trillions of money funding about to be released from bank deposits and prime money funds, which if anything will be driving wholesale money rates down, not up.

While I respectfully disagree about the RRP providing a floor (repo fails, specials and all that), I think his suggestion about the IOER going up with “no consequence for other money market rates” is likely correct. But I also think the fact that some money rates, including the dead federal funds rate (effective), have already taken flight also suggests another scenario altogether – that B to C could or will be a total mess. This is essentially the same scenario that I think has been acting out since November 20, 2013. In other words, there will not be any normalcy, and any attempt to go backward undertakes what amounts to incalculable risk of being disastrous (that is why, I believe, credit market bearishness, flattening yield and money/eurdollar curves, and any number of paradigm inflections in various markets all date back to around November 20; that “something” occurred as a consequence of the taper selloff that more than suggested getting out of QE’s and such was nigh impossible. That such a sentiment has lasted now almost two years forms the basis of what I have called the Fed’s suicidal tendencies toward ending ZIRP).

I personally find way too much complacency in blindly believing that going from B to C will be only a minor inconvenience. It would be dangerous even under the circumstances where the system shifted from the dealers to the Fed and back to the dealers, with an infinite series of potential dangers even there. But to undertake a total and complete money market reformation from dealers to the Fed to money funds? There are no tests or history with which to suggest this is even doable under current intentions. Poszar and Mehrling’s contributions more than suggest that difficulty, but I think that still understates whether or not we ever get that far.

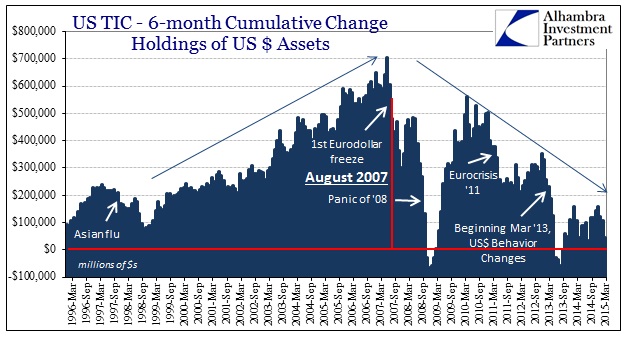

Clearly the entire eurodollar system has been undertaking pains of withdrawal all the way back to August 9, 2007. What is at issue is what might constitute that second transition, to get from B to C. Poszar’s scenario is one of a relatively familiar C, with some difficulty in achieving it (largely in the Fed “holding its nose” about the RRP’s) and Mehrling (and I really don’t want to speak too much for him) looking maybe a little past that. My position is that the transition has already been rocky and with some very dangerous results so far (October 15, January 15). The Swiss National Bank can attest.

The first rule of military planning is that no plan ever survives first contact; in money market planning we have already seen the metaphorical bullets all over the place. That may not necessarily derail the intended transformation, but I wouldn’t discount that in the end what comes out looks nothing like even the C’s envisioned here. After all, heading toward late 2007, hardly anyone could see that A would prove so unworkable as to force even shifting to B, and that B looked nothing like what anyone dreamed it would. Paradigm shifts are always messy, and financial and funding markets since November 20, 2013, have been getting more and more nervous about it all. In many ways that is understandable given the gathering preponderance of unknown unknowns coming into view, but also as a matter of wider appreciation that they don’t know what they are doing.

Stay In Touch