Back in early July, Bloomberg published a rather curious article that sounded like it was written from within the People’s Bank of China – or any other global central bank for that matter. The most prominent correlation over the past year had been CNY and everything else; or, as I wrote earlier in the year, CNY down = bad. The Bloomberg piece, written under the byline of Bloomberg “news” no less, acknowledged that but with a determined emphasis on it being a historical artifact and nothing more.

The last time China’s currency was sinking this fast, investors around the world responded by fleeing riskier assets. Now, they’re taking the declines in stride.

Global investors are growing more comfortable with a weaker yuan after China’s central bank improved its communication with markets and took steps to prevent a downward spiral of depreciation and capital outflows. HSBC Holdings Plc sees little chance of a return to January’s turmoil, while Beijing Gao Hua Securities Co. says the Chinese currency will be stronger against a basket of trading partners by year-end.

“This time, it’s different,” said Song Yu, the Beijing-based chief China economist at Gao Hua, the mainland joint-venture partner of Goldman Sachs Group Inc. He has been the top-ranked forecaster of China’s economy since Bloomberg began its ranking in 2013. “The recent depreciation in the yuan didn’t result in large volatility in financial markets around the world, and there weren’t heavy speculative positions shorting the currency or individuals trying to convert their yuan holdings into the dollar in a panic.”

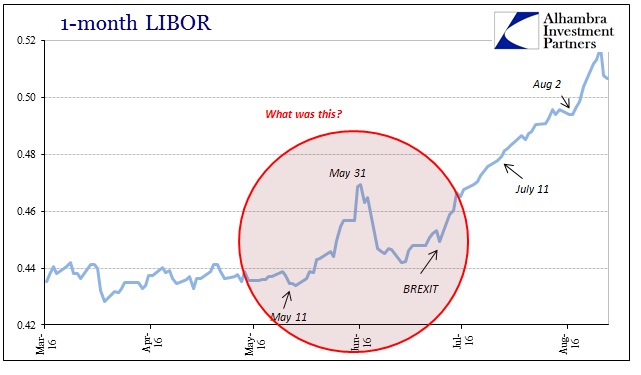

While stocks didn’t sell off in wild fashion again, is it really the case that “the yuan didn’t result in large volatility in financial markets around the world”? We know from the perspective of oil prices or eurodollar futures the assertion is already dubious. This question relates not just to CNY and its central role as a “dollar” indication, but maybe even more so to the current highlight of irregularity and what that might mean if anything has really changed – LIBOR.

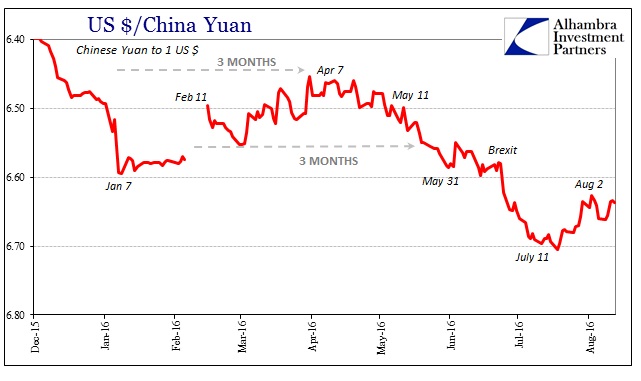

For CNY, it starts with May 11, really February 11. That the last liquidation ended on February 11 is not coincidence given what happened in China. Thus, three months later right on schedule CNY was predictably experiencing heavy “depreciation” once more; the “ticking clock.” By May 31, CNY was all the way down to about 6.60 again.

As CNY was falling, was the “dollar” world really so uninterested?

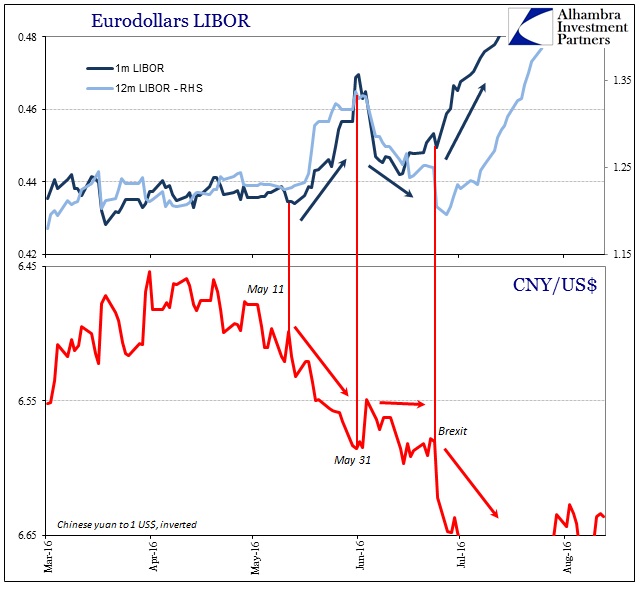

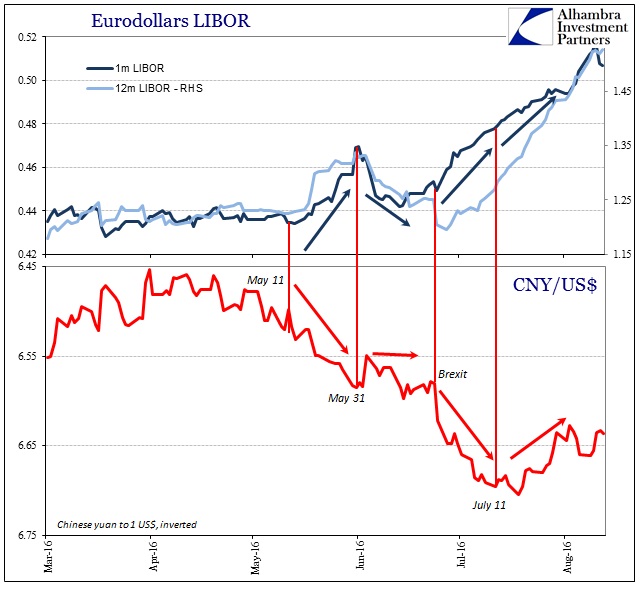

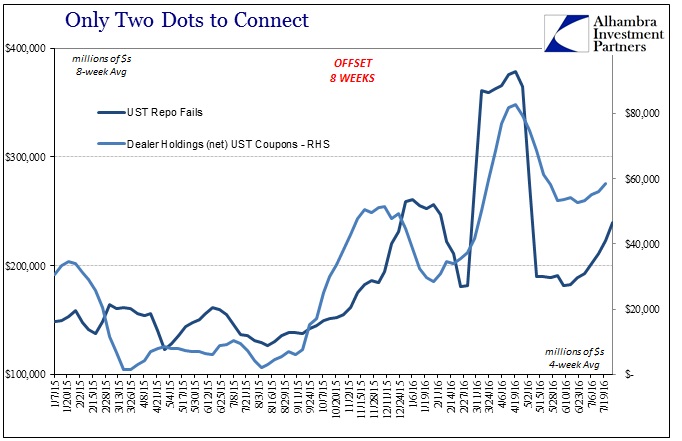

Examining LIBOR in whatever maturity, we find that may never have been the case at all. The mainstream continues to asset that 2a7 reform is alone responsible for rising LIBOR, yet from mid-May to mid-July there was an undeniable inverse correlation between CNY and LIBOR. It doesn’t suggest money market reform so much as general, acute illiquidity.

The timing, direction, and even intensity are all right there. From May 11 until May 31, CNY dropped in almost a straight line indicating “dollar” stress and LIBOR strikingly corroborated. Then, for some still unknown reason, both CNY and LIBOR stopped. A few days into June whatever had occurred was further aided first by the May payroll report (“selling dollars”) and then doubts about Brexit. From there until July 11, CNY dropped again in very much the same fashion as in the latter half of May, with LIBOR in tow (or CNY following LIBOR). The replicated pattern is found to varying degrees at all LIBOR maturities.

It raises some serious questions (subscription required) about what is going on in London, and further suggests what might be different about this year as compared to last year.

That might propose that “dollar” supply via the Asian “dollar” was different and relatively much deeper (and maybe limited to FX?) than perhaps London eurodollars that we think of using that term. Is “someone” perhaps supplying “dollars” to Asia that at the same time removes them from London? Redistribution is more likely to occur, as we know from China alone, under duress than otherwise.

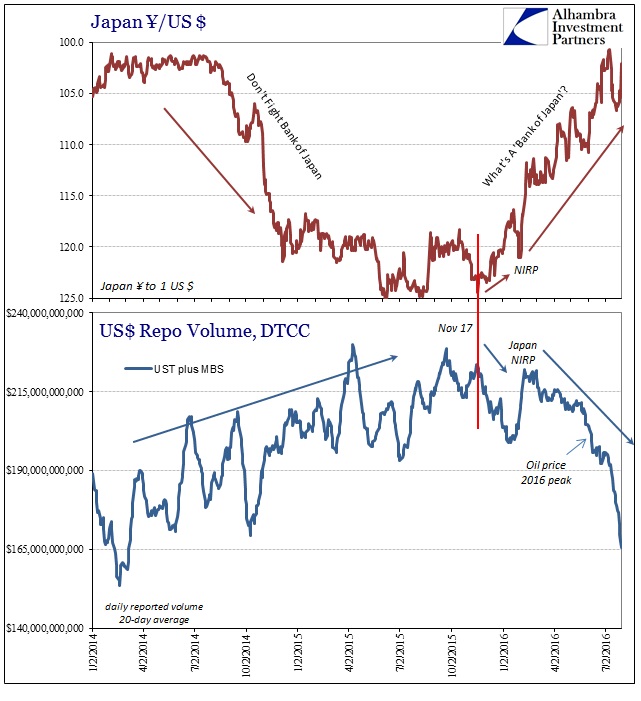

Something did change on July 11, however, and not like what Bloomberg proposed. Prior to that date, LIBOR had moved predictably opposite CNY; up, down, and up again. If the rest of the world was ignoring CNY until July 11, now after that date even CNY ignores LIBOR. July 11 was, of course, the rumors of the Japanese helicopter. Just the action in CNY alone suggests further PBOC activity and interference; the now diverging surge in LIBOR just may propose more than that.

The mainstream wishes this would all go away, clearly, but might there be more than wishing at work (subscription required)? That’s the morbid beauty of these kinds of “bumps” that so clearly stand out. LIBOR, as repo or JPY (or repo and JPY), tells us to believe our own eyes that connect all these seemingly otherwise unrelated dots. Nothing to see here?

Stay In Touch