Speculators are a curious bunch, not in what they do or how they do it but more so in how and really when they attain notice. When the SEC in July 2008 banned naked short selling of GSE and primary dealer stocks, they were the obvious enemy creating “unnecessary” trouble that was amplifying what was supposed to be in the end no big deal. By February 2013, however, speculators were only mildly chastised for maybe going a bit too far in the direction Ben Bernanke explicitly stated he wanted for them; whether it was buying small cap stocks at increasingly “stretched” valuations (now being joined by all caps) or junk bonds at record low spreads, speculators moving in the same direction of policy were just suggested as “reach for yield.”

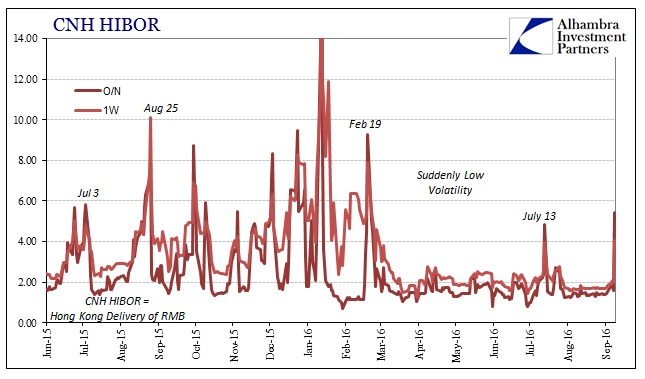

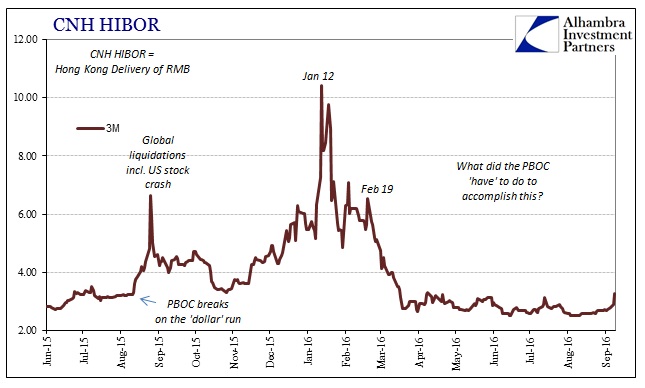

And so it is that whenever market prices deviate by whatever counts for “too far” but only in the opposite or wrong direction, speculators are to be highlighted and destroyed. Nobody ever seems to go back and really analyze why it was “too far” in the first place. The Chinese provided what stands to now as perhaps the best example but only in the mainstream conception of it. On January 12 this year, amidst global financial (and related economic) chaos, the offshore lending rate for Chinese RMB (CNH) surged to unbelievable levels. The overnight rate in CNH HIBOR (meaning unsecured interbank in Hong Kong) hit 66.815% that day; the 1-week rate 33.791%.

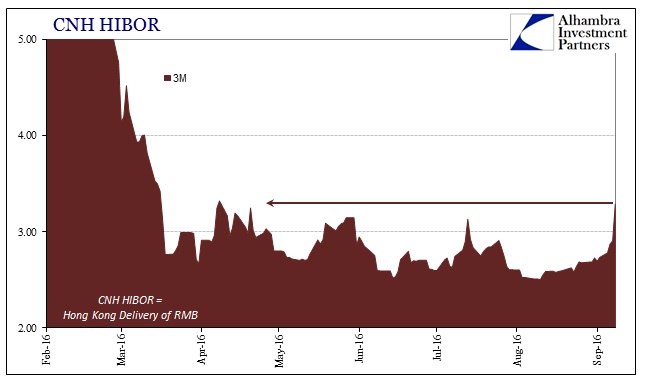

These were clear efforts on the part of someone, though it isn’t immediately apparent that it was the PBOC; nor is it readily apparent that if it was the PBOC that it was speculators who were the intended target. Looking at the HIBOR charts from before and after the early February and it is immediately obvious that what was chaos on the left side was far more orderly on the right.

In my view, that takes ongoing effort, perhaps great effort, not a one-time, one-off warning to speculators. Even if it was all directed at the devilish side of markets, what PBOC policy were these so-called speclators thwarting in CNH? The only answer is a stable CNY, which means that CNH speculators are borrowing Hong Kong offshore to arbitrage onshore illiquidity related to external (“dollar”) funding.

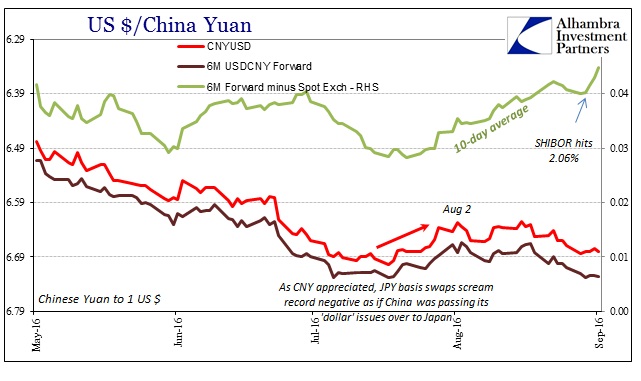

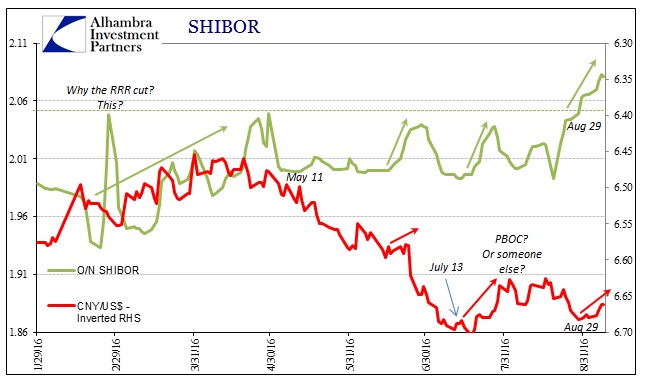

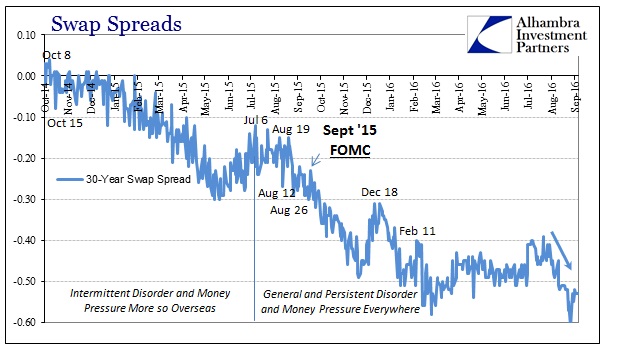

Fortunately for us, there is evidence on all those counts as noted yesterday to start. Global “dollar” balance sheet problems of late? Swap spreads. Unusual RMB onshore illiquidity? O/N SHIBOR at 2.08%. Strange action in CNH? Yep:

The overnight rate in CNH HIBOR jumped to 5.446% today according to the Treasury Markets Association, the highest since February, more than the short spike in the middle of July. That episode actually helps to further illustrate these wholesale mechanics, especially since the rise then occurred right around the time CNY was careening out of control toward 6.70 and perhaps beyond. In the conventional narrative, it would have meant an increased interest in “shorting” CNY via CNH as it looked like the PBOC might be letting it go again.

Since then, however, it seems as if 6.70 has become a line to defend by wholesale policy action. But you can’t have it both ways; the Chinese central bank can’t maintain two pegs simultaneously. Either SHIBOR would have to be let go or CNY. Thus, perhaps it is not speculators (or at least how the mainstream views them) that is leading to the action in CNH now.

The difference in September versus July is SHIBOR, meaning that illiquidity onshore is some factor greater now than during early summer. That all comes back to what I wrote yesterday about the relationship “dollar” to CNY/RMB:

Since the Chinese economy is funded in externalities (especially “dollars”) as much as internal bank reserves and true money policies, the problem of SHIBOR was revealed as a function of increasing pressure placed on the Chinese system as a result of the then building “dollar” run. In response, dating back to that March, the PBOC had pegged CNY exchange as a workaround, increasingly stamping out any volatility in CNY (to the dollar). What that really meant was that the PBOC was attempting to fill the funding void left by Chinese banks unable to pay the required premium (in lower CNY exchange) to bid in eurodollar markets (repo, unsecured, FX, etc.).

But as the Chinese central bank was actively using its wholesale “dollar” means it was at the same time restricting RMB liquidity. Thus, it was established that because of this money market arrangement (external/internal) the PBOC can only pick one to control. Of course, for a time in August 2015, funding pressures had become so disorderly that the Chinese had control over neither – and it was within this exact period that global markets (mini) crashed the first time.

From this perspective we see that CNH “speculators” are “betting” on CNY “devaluation” not as a matter of policy but of greater “dollar” strain. Perhaps the better way to translate that into wholesale terms is that by sticking with CNY the PBOC is risking illiquidity in RMB in all its forms, offshore as well as onshore. Again, the rise in SHIBOR past what was a durable and policy-created ceiling is already an indication that pressure is really building, a supposition that is greatly bolstered now by what just happened in CNH.

The media, however, doesn’t know what to make of this, instead publishing speculation (pun very much intended) that speculators are betting on devaluation as a matter of currency policy after the G-20 summit.

The People’s Bank of China may have tightened liquidity in the offshore yuan market to control declines following speculation that it would allow depreciation now that a Group of 20 summit is over, according to Mizuho Bank Ltd. The monetary authority drove offshore yuan borrowing costs to unprecedented levels in January in an effort to punish bears.

“The authorities may be repeating January’s trick — tighten liquidity and crack down on bearish speculation on the yuan,” said Ken Cheung, a foreign-exchange strategist at Mizuho Bank. “Everyone was talking about depreciation after the G20 meeting, and China could be reacting to that.”

How many more times does the PBOC have to prove that “devaluation” (at least against the dollar) is not their intent? It is abundantly clear that official central bank policy is to stabilize and really bring about appreciation for CNY whenever possible. Thus, “devaluation” is those times where intended policy is not possible without resorting to “too much” effort. That means that problems in CNH relate to increasing concerns and perceptions of or about “too much effort”, meaning “dollars” (swap spreads as the possible “unusual” there).

What this suggests for the intermediate term is obviously still unclear. My contention yesterday was simply that Chinese money markets in RMB related to “dollars” remained a mess (and not a 2a7 mess) but now unusually so by the standards of O/N SHIBOR suddenly at 2.08%. O/N CNH HIBOR now at nearly 5.5% just adds more depth to the idea of “unusual” in global money.

Stay In Touch