In 1927, physicist Werner Heisenberg wrote in his paper defining the “uncertainty principle” that, “the more precisely the position is determined, the less precisely momentum is known in this instant, and vice versa.” It has also been called the “principle of indeterminacy” which simply means that you can only pick one variable. By doing so, you lose any chance for accuracy about the other.

So it is in central bank money markets, a long established proposition that predates the latest “proofs” on display once again in China. It had always been the case that a central bank could pick quantity or price, but not both. The Chinese experience in the “rising dollar” period is bit more refined than that, however, a position that you can be sure they do not relish. Furthermore, it seems as if there has is another dimension to this behavior whereby only Japan or China can be at less issue at any one time; not both.

As I wrote on Friday (subscription required):

After having ceded so much attention to Japan and JPY over the summer, it does appear as I indicated last Friday that China is having enormous trouble with CNY, threatening to take back the central pivot in “dollar” indications from the Japanese.

Clearly they don’t want it but have no say in the matter (which is the only thing that has truly mattered this whole time). There are only two possibilities now that HIBOR has been drawn in where SHIBOR has finally gone: that the PBOC is, as the mainstream suggests, attempting to stamp out speculators betting on further devaluation, or by paying so much more attention to CNY since mid-August that offshore RMB liquidity has on its own become as seemingly impaired as onshore.

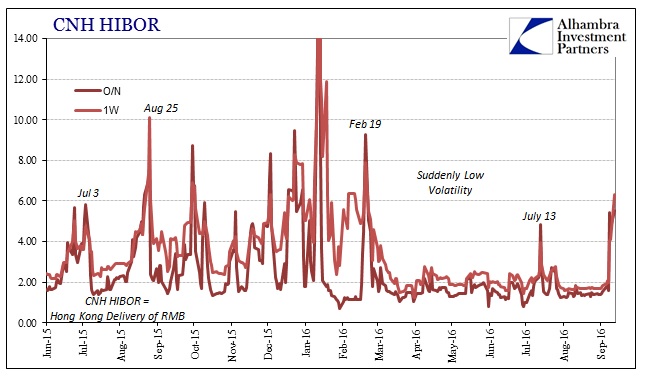

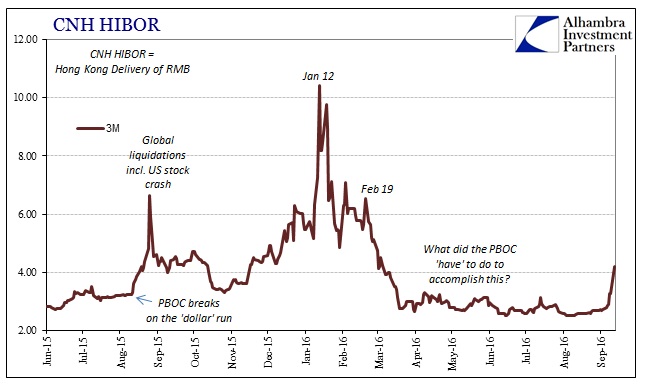

The idea of HIBOR (offshore RMB, not Hong Kong dollars) being a central bank tool dates back to January when for two days the unsecured lending rates were pushed beyond all proportional sense; the O/N rate spiked to 66.8% on January 12. Occurring amidst the very center of the global liquidations of the time, there was actually some sense to it as a matter of possible policy effort. Floundering in CNY “devaluation” was the most crucial indication of everything wrong at the time. As the indicated central bank, the PBOC had every interest in doing whatever it could to arrest the currency decline that people still think of as export stimulus.

This time, however, HIBOR (CNH) has simply joined SHIBOR (CNY) and now for a third day. I wrote last week that I was more inclined to view offshore CNH illiquidity more as total RMB illiquidity rather than the PBOC taking another shot at “speculators.” Today’s rates, I believe, further express that position.

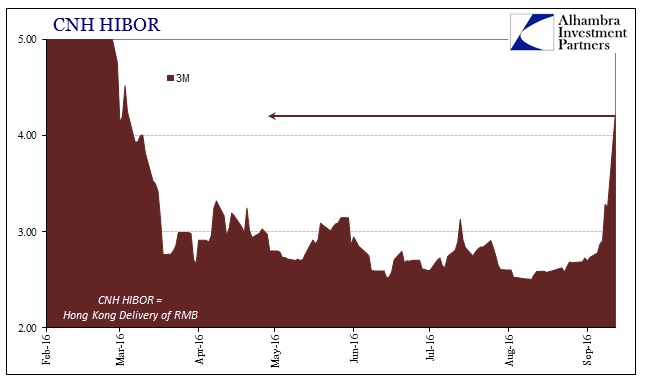

The one-week rate is substantially higher than overnight, while the 3-month rate, the more important benchmark position, jumped to 4.21% this morning, the highest rate by far since March 4.

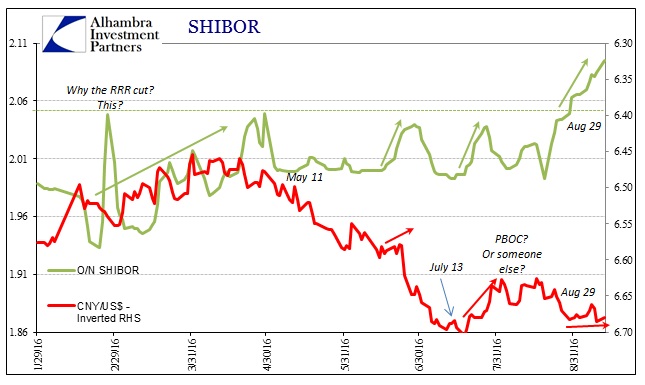

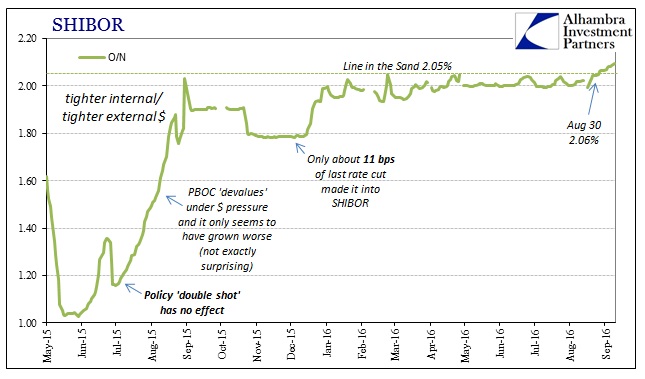

These RMB rates both onshore and off suggest that “something” is different of late, a fact we know well by overnight SHIBOR (onshore) breaking above 2.05% in late August. Though the CNY exchange rate was allowed to fall rather sharply on Friday, which in the past had usually led to reprieve in unsecured liquidity especially onshore, it did not last week and was not followed through with more today. It seems increasingly clear that since mid-July, the PBOC has redrawn its “lines in the sand” such that it now prioritizes CNY above 6.70 (so much for export “stimulus”).

The problem of picking CNY rather than SHIBOR is this money market “uncertainty principle” where if you hold steady the currency (thus “dollars”) you have to let internal liquidity deteriorate. The test came on August 30 when the overnight rate in SHIBOR moved above 2.06% and the PBOC let it by holding fast to CNY. It has only paused in its ascent for one day since then, fixing at 2.095% today. Again, in my view, that internal RMB problems spillover into offshore RMB is quite natural as a matter of further pushing “uncertainty.” The more “precise” the Chinese central bank may be with CNY, the less precise they will be in RMB no matter where it trades.

It seems as if the Chinese after spending more than a year trying to interrupt the forces of disruption (“dollar”) they have come full circle back to where they were last summer: rising SHIBOR set against steady CNY. It had started then around June 1, 2015 (the PBOC had pegged CNY going back to mid-March 2015) and lasted just more than two months before the central bank lost all control on all sides on August 10. While many still struggle with what that meant, it was simply the perhaps inevitable outcome where the steadiness in CNY was increasingly shutting out Chinese banks from eurodollar markets (they couldn’t “pay up” for “dollars”) while at the same time increasing the cost and inefficiency on the part of the PBOC in holding CNY steady.

Those two trends intersected in mid-August and delivered amplified “global turmoil” that altered the global economy. The intense rumble of selling in global markets on Friday was a hint that it may not be just China revisiting last year’s conditions.

Stay In Touch