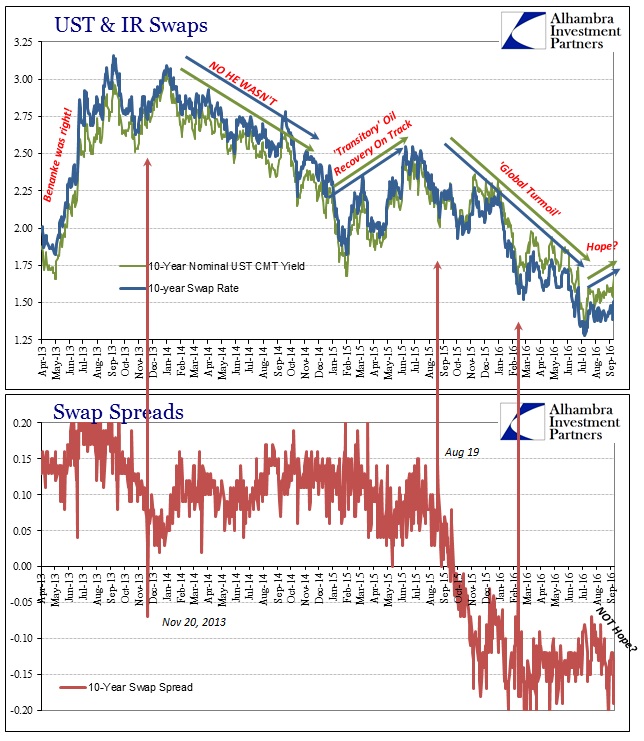

The yield on the 10-year US Treasury closed at around 1.68% today, but judging by the haughty commentary surrounding global bond markets you would be forgiven if you thought it was 2.68%. Since the low in July around 1.37%, that +30 bps apparently seems like it to many people. Going back to the end of QE2, the idea that rates have “nowhere to go but up” has been a constant presence during each and every bond selloff since then (and there have been a few).

The reason is that nobody seems to understand what interest rates are telling them. The only goal the Federal Reserve ever accomplished was convincing the world that it was powerful and mighty, a PR campaign sourced out of the so-called Great “Moderation” that lingers on even today after having been thoroughly disproven time and again (especially about “moderation”). So much of the world, especially in and around official channels, simply wants to believe in the technocracy and general technical competence that was only assumed of the Greenspan Fed.

And so it is with bond markets. Even the Wall Street Journal today writes up the angst over the bond market’s most recent move, classifying it in just those terms.

The selloff in government bonds that started last week continued to ripple through financial markets on Monday as investors dialed back their expectations of future central-bank stimulus.

Investors are now asking whether markets are on the verge of another so-called bond-market tantrum, in which yields rise sharply as prices fall. So far, most conclude that markets are not. Many investors believe that central banks will continue to provide aggressive stimulus because economic growth and inflation remain low.

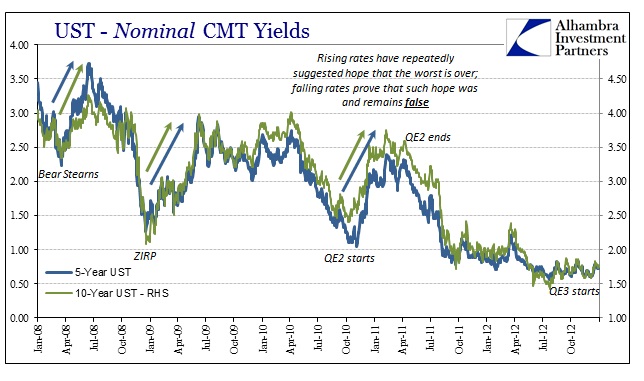

It is the paralyzing “paradox” that plagues what used to be known as “forward guidance.” In other words, if “stimulus” actually worked, the bond market would price that as higher rates; not lower. When the economy actually does recovery (some day in the distant future, a point in time that will be determined by monetary reform not typical market gyrations) the UST curve will rise and steepen – just as it did during 2013’s “taper tantrum.”

This bond market riddle is, as I wrote in July, not a riddle.

They all assume, all have assumed, that economic weakness is just some temporary phase, an inconvenient speed-bump that will surely fade as monetary genius further asserts itself. It was a dubious prospect in 2013 where unbiased analysis of the global economy only showed increasing doubt and trouble, but it is much more so in 2016 where “transitory” can no longer apply.

Governments are heavily bid during times when it appears as if the economic darkness is increasing, and they sell off when that fear subsides. Since 2013, this back and forth has taken place several times. Indeed, at the end of 2014 and the start of 2015 the UST curve flattened and lowered by a concerning amount, coincident to all sorts of “unexpected” and “transitory” factors. The 10-year yield sank as low as 1.68% on January 30, 2015, about where it is now.

By early March, the yield was back nearly at 2.30% again, which elicited the same kinds of responses as we find now. And though that was a much bigger selloff, and actually would continue in parts all the way into early June 2015 (with the 10s moving above 2.40%), it didn’t represent anything more significant than the diminishment in negative attitudes right at that time. Fundamentally, nothing had changed; Janet Yellen’s “transitory” narrative for a time just seemed somewhat more plausible (only to be shattered yet again).

And so the mainstream keeps calling for a bond market reversal based on a fundamentally flawed proposition; a recurring mistake in just these kinds of extra-cyclical conditions where the usual rules and expectations of “stimulus” and policy just don’t apply. The UST market, among other bond classes, as it goes only lower (in yield) tells us that the economy is getting worse (which is what we actually find here and all over the world). Economists and econometrics don’t believe it because they are hardwired not to; to them, monetary policy always works, therefore rates will have to rise as the economy that should be must be just around the corner.

From that utterly backwards view, persistently falling interest rates are an absolute mystery; a riddle without answer. The proper, unbiased perspective shows there is no riddle at all, only that the bond market (and “dollar” markets) has been right this whole time. UST yields are not backward-looking proof of academic concepts, they are a tested and verified forward-looking warning of what is to come.

Low interest rates tell us nothing about “stimulus” except that it has been judged entirely ineffective, even irrelevant as in the case of the “dollar” and global money supply. The “taper tantrum” at least in terms of UST’s (currency markets and other funding indications were an entirely different story) was actually the bond market trying its hardest to actually believe in Ben Bernanke for a second time. It didn’t last long, and UST’s by late 2013 first in yield curve flattening began to reject the recovery scenario all over again. The reason treasury rates are in 2016 closer to record lows even after this selloff than anything like 3% or 4% or more (as was extrapolated in 2013 by “rates have nowhere to go but up”) was given by Milton Friedman as far back as 1967.

These subsequent effects explain why every attempt to keep interest rates at a low level has forced the monetary authority to engage in successively larger and larger open market purchases. They explain why, historically, high and rising nominal interest rates have been associated with rapid growth in the quantity of money, as in Brazil or Chile or in the United States in recent years, and why low and falling interest rates have been associated with slow growth in the quantity of money, as in Switzerland now or in the United States from 1929 to 1933. As an empirical matter, low interest rates are a sign that monetary policy has been tight-in the sense that the quantity of money has grown slowly; high interest rates are a sign that monetary policy has been easy-in the sense that the quantity of money has grown rapidly. The broadest facts of experience run in precisely the opposite direction from that which the financial community and academic economists have all generally taken for granted.

The financial community, in general, and academic economists, as a herd, still take it for granted. Rearranging our terms somewhat, the bond market selloff (treasuries) in early 2015 was a little more faith that “transitory” was correct and that the real economy would start experiencing real monetary flow again after the oil crash and “dollar” disruption of the first part of the “rising dollar” period. It was, essentially, the idea that there might be only one part to it in total. But, as UST rates showed once the seasons flipped into summer last year, that wasn’t ever a realistic expectation, and rates moved sharply lower again though not at all in a straight line.

The “rising dollar” has had real economic effects which are being reflected by government bond rates all over the world – even at this moment. After the usual spring rebound again in 2016 and the lack of immediate crash in summer (though in many economic accounts that isn’t the case), the hope for monetary flow has been reborn if somewhat more restrained this time (with good reason) again in the absence of more obvious global “dollar” pressure.

So long as monetary disruption is indicated, however, interest rates will remain on their overall lower trajectory – just as in the 1930’s. This is the “riddle” that plagues mainstream bond analysis, particularly given conventions on central bank power and QE’s assumed effectiveness. That is one of the primary reasons that so much unusual action in Japan and now China is importantly indicative; it shows the “dollar’s” negative effects have continued if only sunk into the background just as before during prior UST selloffs.

As long as the “rising dollar” remains, so does “tightness” in the real (global) economy. Interest rates will reflect that baseline, just not in a straight line nor at all times.

Stay In Touch