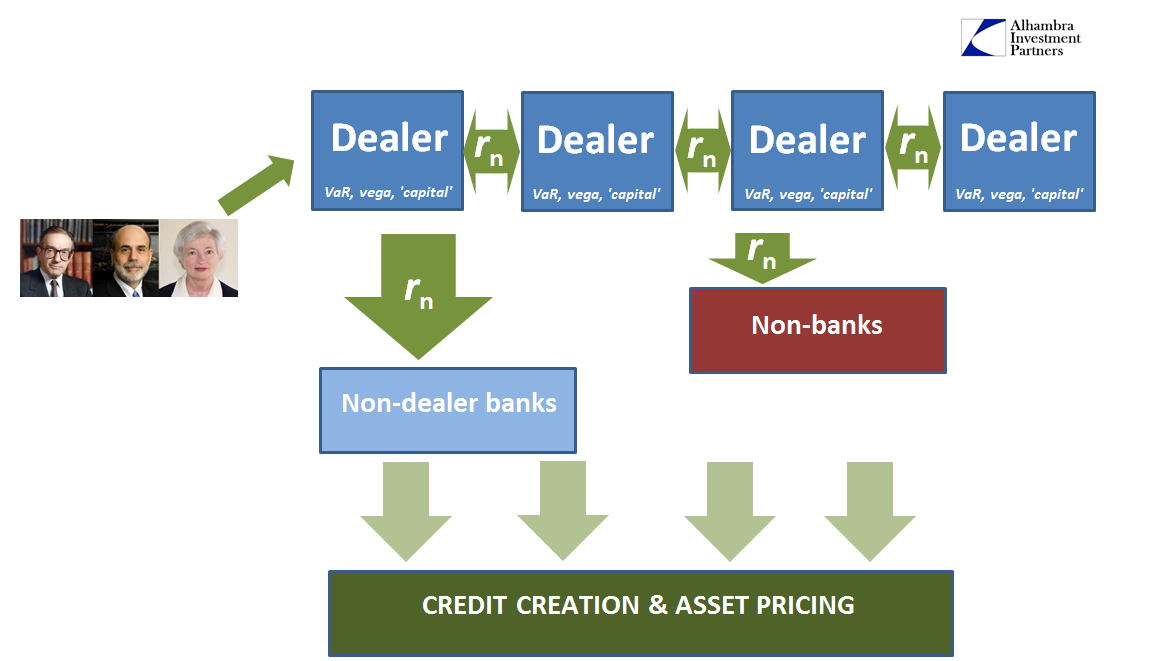

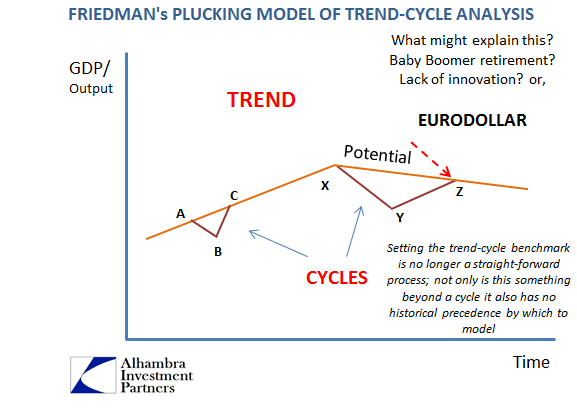

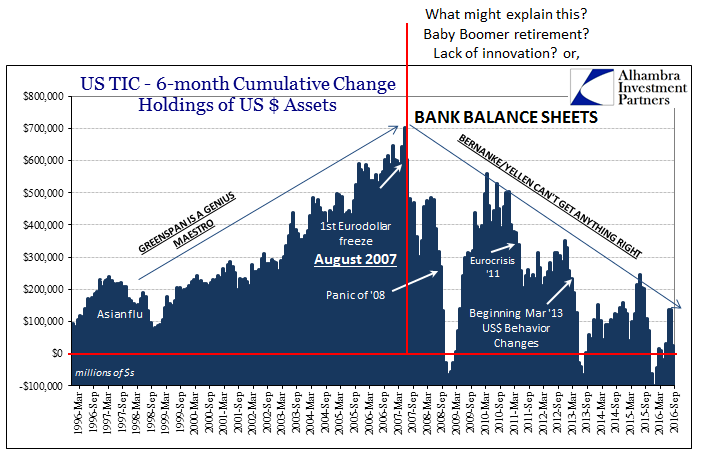

The whole monetary issue as it pertains to the eurodollar system can be succinctly summed up as balance sheet capacity. In pure monetary terms, that is an enormous distinction. What counts as money is not what almost everyone still thinks it is, though those view should have been shifted almost a decade ago in August 2007. Money is instead “money”, where all the various forms of those bank balance sheets become the conditions that drive either monetary growth or contraction. Indeed, it is in many ways impossible now to separate money from credit, a further complication that has only rarely been considered.

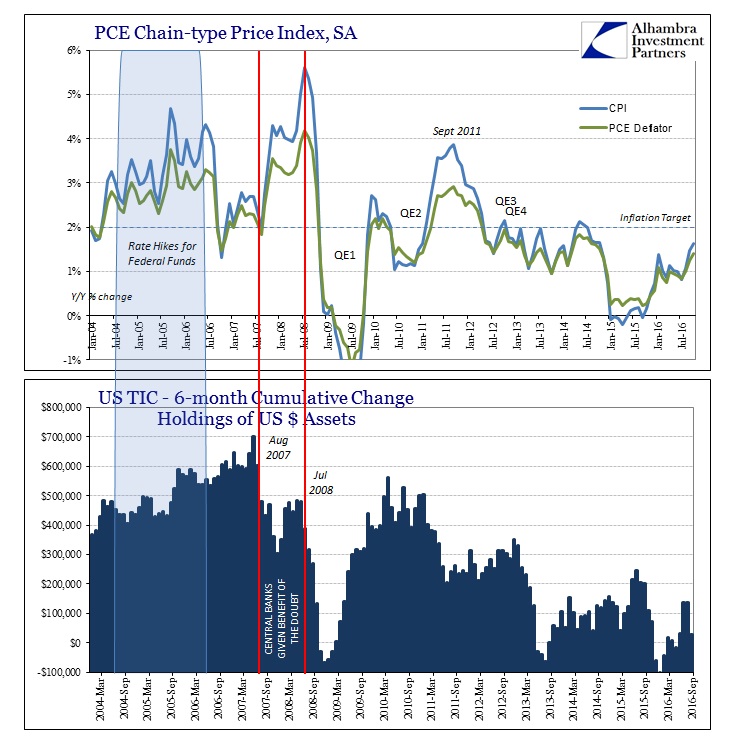

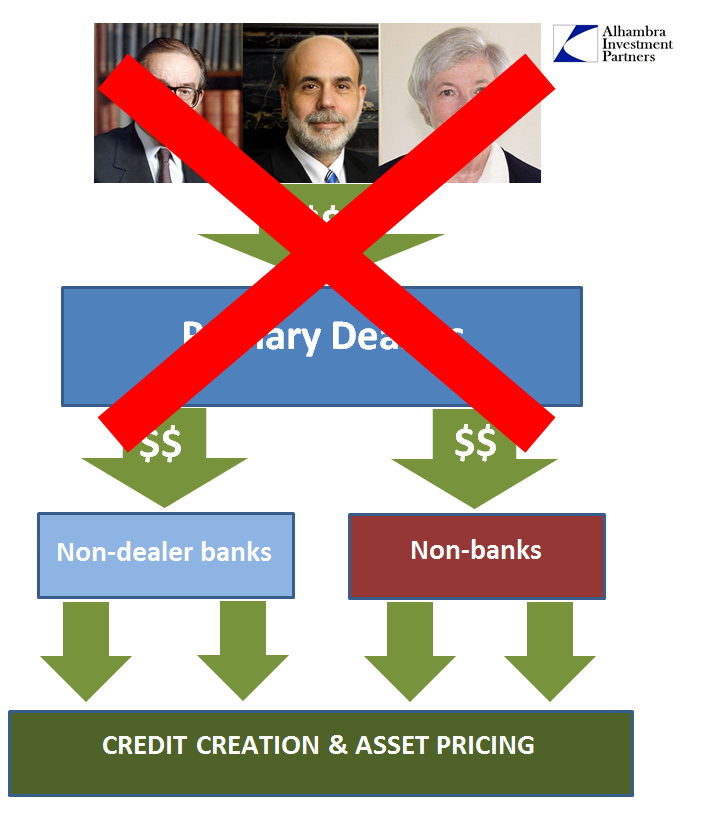

The problem from a monetary policy standpoint that might ever acknowledge this arrangement is that it diminishes greatly the standing of monetary policy and the central bank. To realize that banks are at the center rather than central banks would be for monetary policy to be reduced to one input among many; and, more often than not, especially the past few decades, an unimportant one. We need not search very long for examples of this, as Alan Greenspan’s “tightening” that tightened nothing including calculated inflation in the middle 2000’s is a perfect pre-crisis demonstration of near irrelevance.

On this side of the eurodollar breakdown, the whole affair is and has been, essentially, one of monetary policy impotence; no matter how hard they try, nothing works. The reason is that bank balance sheets are being driven by very different factors, some of them actually related to the failures of QE rather than how they were supposed to have been money printing.

What should be on everyone’s mind now is why it took more than a decade of such direct futility for all this to finally sink in.

The European Central Bank’s money printing scheme is not enough on its own to lift growth because banks in the euro zone are not transmitting cheap credit to the economy due to heightened uncertainty, Governing Council member Ilmars Rimsevics said on Friday.

“It is crucial to understand why commercial banks are not providing sufficient credit to the real economy and why business does not stand in line at banks to borrow money,” said Rimsevics, considered a moderate conservative on the ECB’s rate setting council…

Still, even after 1.5 trillion euros of asset buys, credit growth is lackluster, raising questions about the effectiveness of the scheme, known as quantitative easing.

It’s not even close to appreciating and recognizing the eurodollar system, but it is for once a step in that direction. And it’s not quite the message the Latvian central banker had in December 2014. Though Rimsevics had been arguing consistently for more than just monetary policy as a base of “stimulus”, he was at least confident in the runup to European QE to project as much in his official capacity as Governor of Latvijas Banka.

At the same time it was decided that at the beginning of next year [2015], the ECB Council will evaluate the performance of the existing monetary stimulation measures, increase in the ECB balance and inflation development, assessing also the impact of oil prices on the medium term inflation. If the existing monetary instruments are not enough to prevent the risks related to too long a period of low inflation in the euro area, the ECB Council will be ready to supplement the existing range of monetary policy instruments. All Eurosystem measures are aimed at stimulating a gradual approximation of the euro area to an indicator that is close to but not lower than 2%.

Instead, 2015 was a watershed year for central banks. Everything they had expected about 2014 was turned away in 2015 so that in 2016 they are now facing up what that means. In many ways, finally, they have no choice. Recovery, as I write, is political and even inside the isolated bubble of central banks these economists can feel the political winds of populism blowing dead set against them.

While in one sense it might be positive that they are just now starting to think about money and banking as it is in reality outside the Economics Textbook, there is truly no excuse to be doing it now at this late date with so much economy lost and so much upheaval the cost of it. It was their job to know better; so that in late 2014 they should not have in Europe wasted all that time and effort on something (QE) that clearly was not going to work. Alan Greenspan was talking about the shifts of money throughout the 1990’s, and the Japanese had been proving Greenspan’s missives and more importantly their implications the whole of the 21st century.

Instead, on December 4, 2014, Mario Draghi said, “QE has been shown to be effective in the U.S. and the U.K… There is enough evidence to say that it could be effective.”

As I wrote for today, central banks have now instead surrendered on QE, but not just QE. It is more than that. When Mario Draghi said “could be effective” he did not define either words “could” or “effective.” In the situation of December 2016, I will wager that how he defines both words today is very different from how he might have two years ago.

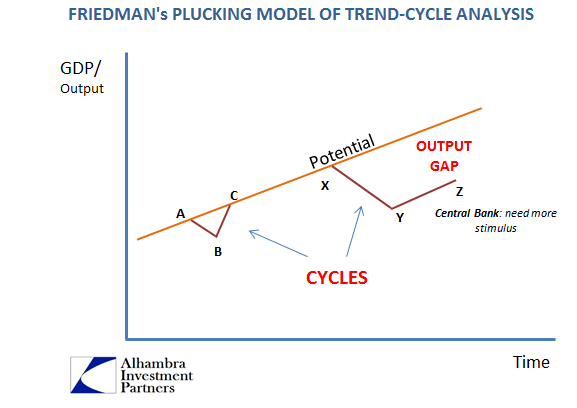

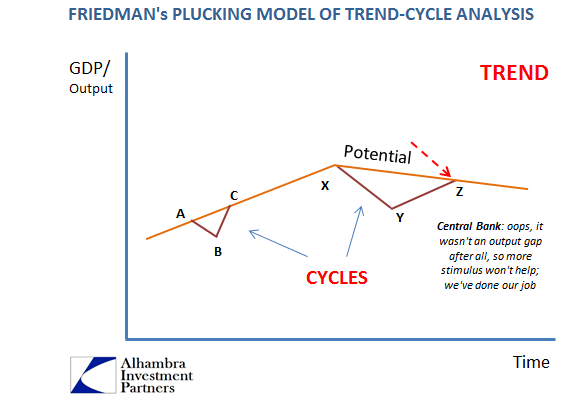

If you believe that 2% inflation and a true 5% unemployment rate represents the right balance for the right economy, that is where you stop. If you believe that 2% inflation and a questionable 5% unemployment rate shows up, you might continue with “stimulus” in the belief that those questions will be answered with enough time and accommodation. If the 5% unemployment rate instead remains highly questionable no matter what, then monetary neutrality demands that you start to accept that that is just the way it is (I am using US numbers here in these examples, they are different, obviously, with different variations and mixes in other places).

Central banks threw everything they had at the global economic problem, and still it all came up short. In a twisted way, the “reflation” impulse was born from just this; that in being forced to deal with this reality rather than the “could” and “effective” of 2014, central banks will now go back to the drawing board and now come up with the right stuff.

But in order to do that, central bankers must first come to terms with what is actually wrong that QE did not, could not fix. As ECB Member Rimsevics’ statement at the top shows, that’s not something that can happen overnight. The ECB tomorrow, or next month, or next year is not going to overthrow half a century of economic theory (really Economic theory) even if it is the right thing to do consistent with actual scientific principles. There are a great many good people within the ECB (or the Federal Reserve) who do care about the truth, but central banks are political bureaucracies, not salons of high-minded free thinkers. In other words, even if the politics of the populist uprising do force the bureaucracy in that direction, the route it will take will not be the most direct and efficient – by its very nature it cannot be.

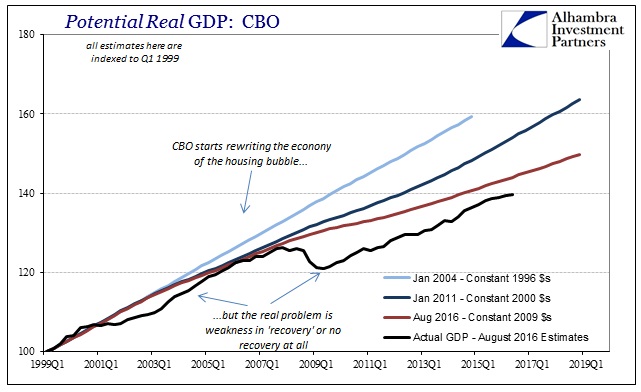

The real danger to “reflation”, however, at least in whatever part is devoted to monetary policy, is that there is the very real prospect that this is it; there is no next set of policies to possibly be effective where QE wasn’t. That is what is suggested in all the rhetoric, discussions, and new literature about central bank’s sudden appreciation of a very different long run potential. Again, the Phillips Curve is central to them, and if the sought after balance of inflation and unemployment comes up in an awful economy, then that’s just the way it is (for them). That awful economy becomes their new baseline, and if the current awful economy is consistent with that awful baseline there is in the orthodox view nothing left for monetary policy to do. It has done what it can.

Reflation itself is the fervent belief that there is better world out there, and I also believe that strongly. However, the current fever isn’t to me any different than the one that swept through 2013. The “right” mix of policies doesn’t fix what’s wrong. The awful economy at its awful baseline is not just the way it is, either. It is all so much more basic than that; so basic it has been overlooked for half a century.

Stay In Touch