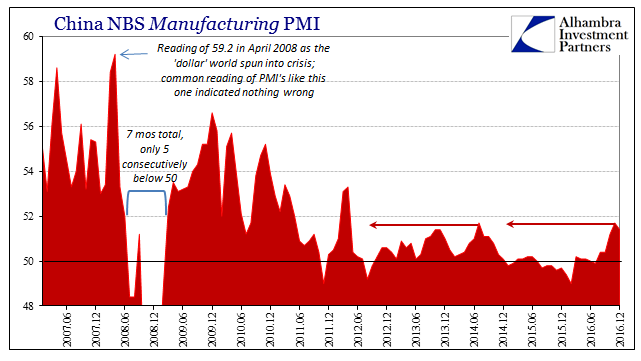

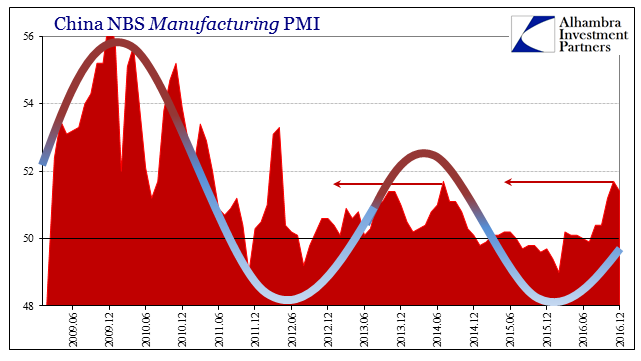

China’s official manufacturing PMI fell just slightly for December 2016, after rising for November to the highest since mid-2014. The overall index pulled back to 51.4 from 51.7 the previous month. The subindex for New Orders remained steady at 53.2, matching the highest point since July 2014. These PMI estimates suggest that China’s experience with the “rising dollar” has passed.

In normal times, that would be a very good development which would herald the start of recovery. The past decade being far from normal, however, it is yet another indication of instead the worst case. The sentiment data in China and elsewhere in the second half of 2016 increasingly resembles that from the second half of 2013. That would suggest, strongly, that China has not really exited the “rising dollar” as euphemism for the ongoing eurodollar problem plaguing the global economy still, rather it has only moved beyond the discrete stage of it that began (“unexpectedly”) in the middle of 2014.

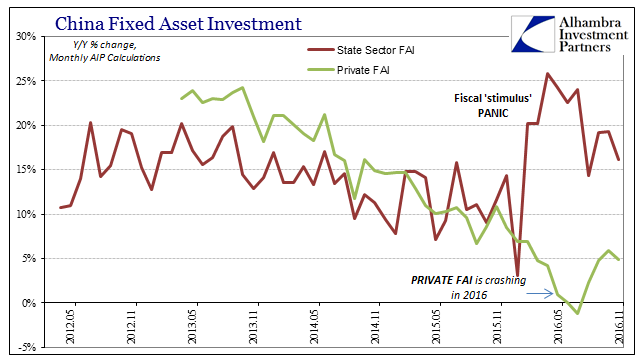

Like 2013, 2016 has seen the injection of “stimulus” on the fiscal side while at the same time monetary conditions resemble the farthest thing from “reflation.” In other words, it only looks better when compared to the universally negative tendencies from the year before. In 2015, like 2012, the Chinese economy as the global economy would only get worse. However, not getting weaker is not at all the same as getting better. For both 2013 as well as 2016, that point is very clear in the historical context.

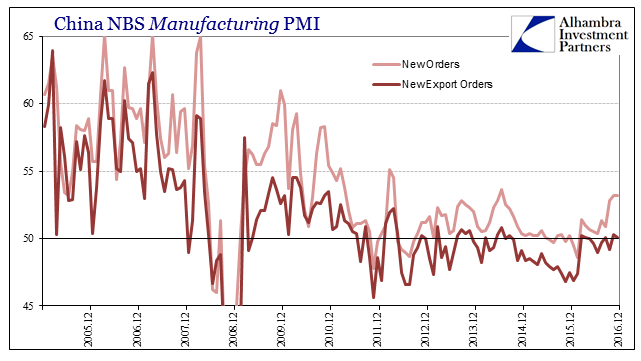

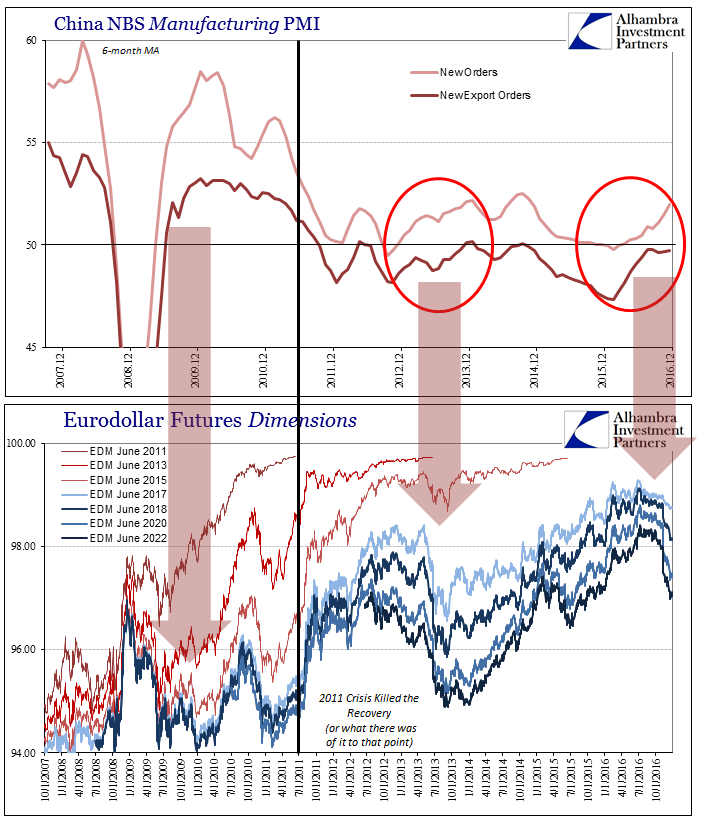

Breaking down the PMI by certain parts, it is much easier to define these distinctions. The difference between sentiment captured by New Orders (total including domestic “demand”), for example, and that of New Export Orders (external “demand” alone) is very likely the introduction of domestic China fiscal spending at the start of the year.

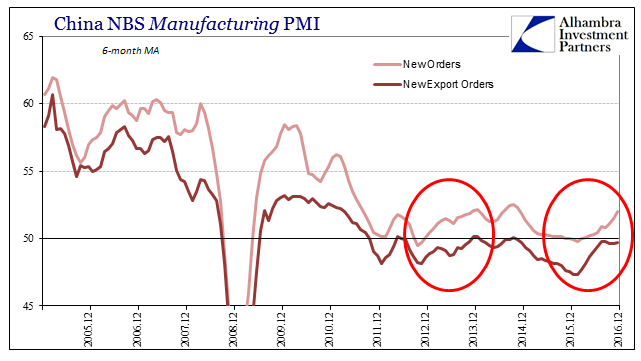

That “stimulus” doesn’t change the overall condition of the Chinese economy, rather it only makes it worse by dragging out imbalances that much further (since the global economy isn’t going to actually recover), while creating others that will have to be added to the ultimate tally at some point now further down the road. This lack of actual and meaningful growth in the Chinese economy is displayed by how even sentiment has remained subdued after the crisis in 2011 (using the 6-month average for each clears up some of the normal volatility).

In that important way, Chinese manufacturing sentiment is an almost perfectly mirrored match for the history of eurodollar futures as I described them last week.

There are clear periods of “reflation” in both, but those shifts in sentiment are not at all like what they would have meant before 2011. What that ultimately means in terms of manufacturing sentiment is not recovery but at best that the Chinese economy isn’t at the moment getting worse. That was the global economy (at least in outward appearance) in 2013 as proved by the fact that it fell off again so easily mid-2014 forward (rather than heading into full recovery as predicted everywhere for practically everywhere).

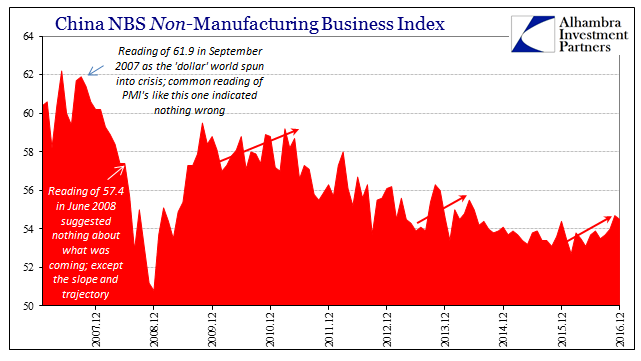

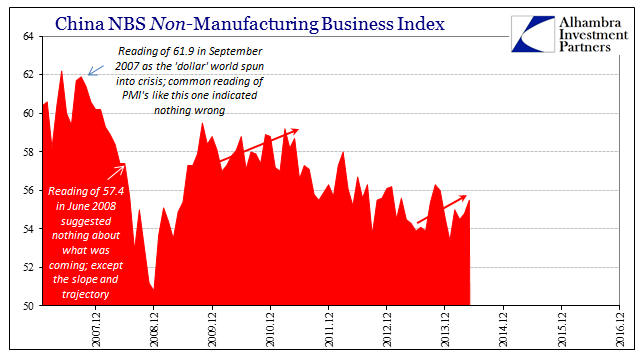

China’s official non-manufacturing PMI displays these very same tendencies and relative conditions, offering then also the same interpretation. The index had registered a multi-year high for November 2016 (54.7), and like the manufacturing version fell back slightly for December (54.5).

If we rewind the history of the non-manufacturing PMI back to mid-2014 and that last jab at “reflation”, we see how it is actually the same pattern (with even more enthusiasm in late 2013 volatility).

These are nothing more that “depression cycles” repeating over and over as overall nothing changes; it is the same economy that is unable to do much more than avoid further contraction. The repetition is established as a tradeoff from contraction (or deceleration) to lack of contraction awaiting only the next contraction. These are punctuated in transition by, again, monetary conditions that are perfectly observable.

If the global economy of later 2016 is the economy of later 2013, then the “rising dollar” will at some point fall into the next phase. The only way for the global economy to have been so synchronized is for the baseline economic trend to have been set by a single set of global money factors (eurodollars). And like 2013, there are so many indications that that “next” phase is already building underneath.

The reason this is the worst case, in addition to the obviousness of overall stagnation, is that “we” never learn from these cycles. The mainstream, especially economists, fall into the trap of declaring recovery each and every time “reflation” shows up. Like the eurodollar futures market, however, faith in those declarations has mercifully dwindled. But like those prior “reflations”, there is always going to be something proclaimed to be “new” and “different” which will tantalize and mesmerize so as to lead many to set aside these lessons.

Nothing has really changed for many years, but there are times when “we” feel better about it.

Stay In Touch