China joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) on November 11, 2001. Its membership took a decade and a half to achieve, no small wonder given that when it started the process the country looked nothing like it did when it was complete. Even by 2001, the Chinese economy was growing fast, but that was nothing compared to what it was about to experience.

From the Chinese perspective, securing a seat at the major trade table was a major step in China’s modernization. As the New York Times wrote at the time:

Chinese officials have presented the nation’s membership as one of their most significant diplomatic achievements since China displaced Taiwan and took a seat on the United Nations Security Council in 1971.

That step decades ago gave China the political rank of the United States and the former Soviet Union. Today’s step ensures China equal status for its fast-growing economy, though in return it will have to grant foreign companies access to its 1.3 billion consumers.

For many, the question is whether WTO membership was the key to China’s miracle. If it was, then what about the other part, where especially US goods were by all expectations supposed to obtain access to the vast Chinese marketplace? If you remember much about the late 1990’s, growth talk at that time was not just about dot-coms as it often centered on which company, tech or traditional, might be best positioned to take off once China was “opened.”

Without examining too harshly, you can appreciate why some might be upset about this particular moment in time. For China, after the WTO it was the best of times; for countries like the United States, not so much. Donald Trump made it a campaign theme often, including remarks during his major “economic” speech given to the New York Economic Club in September last year:

Finally, comes trade – the foundation for everything. America’s annual trade deficit with the world is now nearly $800 a billion a year – an enormous drag on growth. Between World War II and the year 2000, the United States averaged a 3.5% growth rate. But, after China joined the World Trade Organization, our average growth rate has been reduced to only 2 percent.

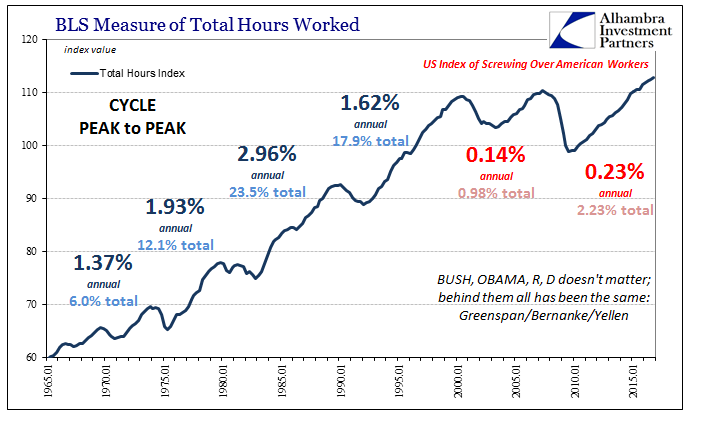

There is clearly cherrypicking in the data, as the 2% figure is most heavily influenced by 2008 and after. Still, Trump was not wrong then to point out America’s misfortunes in the 21st century. Economists refuse to cite the data, but the BLS producing estimates that show clearly “something” has gone disastrously wrong since around the year 2000.

For the first time, a major politician, now actually President, has decided to forgo the mainstream, orthodox Economics excuse of demographics or whatever other passive absurdity has been offered in place of insight. There has been something wrong with the American economy, and while it has been most disturbed in the past decade we should not ignore the precursor warnings in the 2000’s.

That, however, doesn’t necessarily push the blame to the Chinese. Had Trump (or whomever else) made this case in 2007, there might have been some (weak) basis for it. At least then the Chinese were guilty, so to speak, of being evident beneficiaries of “whatever” it was causing these economic disparities. Ten years later, however, it isn’t clear that there are any beneficiaries. As I wrote yesterday:

The issue is not too many cheap foreign goods inundating US markets, as it is instead too little global economy for the prior imbalance to work anywhere.

A quick survey of the global economy shows deep depression in many of the places that supposedly benefited from “free trade” at least in the format of modern globalization. Foreign manufacturers are not still winning at the expense of American manufacturers; nobody is winning anywhere right now. The debate about proper balance is superseded, by a lot, by the necessity of an actual rather than imagined global recovery.

This point is very easy to establish, which is why it is so disheartening to find its absence on the stage. To be clear, I do not defend the Chinese by highlighting this evidence, as my only interest is that we properly frame the disorder so as to as quickly as humanly possible rid ourselves of it. China intentionally went along with global monetary extremes so long as it was in its favor. This does not mean they deserve their current fate, though it does that they share culpability for letting it happen out of ignorance.

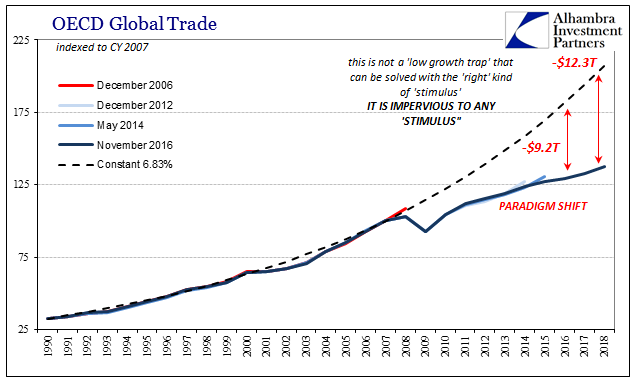

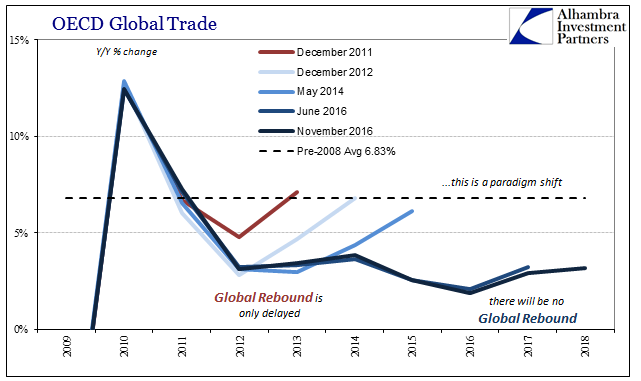

As with all things economic in the world today, the economy as represented by global trade, that which the mainstream refers to as “free trade”, is shrinking. It is growing only in the sense that there are and have been positive numbers posted in all these places after the Great “Recession”, but that gap to the pre-crisis baseline, which is all that truly matters, only grows larger by the year. The estimates for this deficiency are so large now as to be utterly incomprehensible.

The latest figures (November 2016) from the OECD suggest global trade will accelerate only slightly in the next few years, rising 3.2% in 2018 to $24.3 trillion. If the Great “Recession” has been an actual recession global trade “would” be in 2018 instead $36.6 trillion. The world economy is thus poised to be only two-thirds of what it was expected to be a full decade after the assumed end of the affair. This was not, of course, a determination that orthodox outlets like the OECD made contemporarily, rather like US economic potential it has been forced upon them by a very different reality.

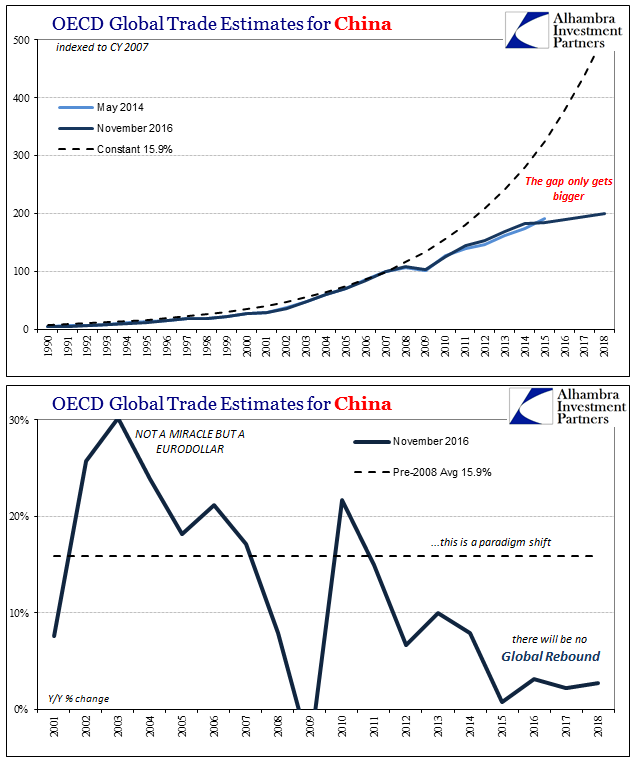

The harshest afflicting of that reality has been on those who once were its primary beneficiaries. This category includes not just China, though perhaps best represented by that country. Because of this, it is impossible to make the case that China continues to steal American jobs in manufacturing.

From 1982 (the starting point for the OECD data on China) until 2007, trade growth for them averaged nearly 16% per year. It was in the middle 2000’s, importantly, where gains were well above that rate for reasons that had little to do with the WTO membership. Like global trade overall, the OECD originally modeled a return to average trade growth but especially after 2012 and then definitively after 2014 they have been forced to give up on that tendency toward mean reversion (a completely paradigm shift). The current estimates show not even 3% growth in either 2017 or 2018.

To possibly introduce an era of protectionism would be the wrong solution for the (somewhat) right reasons. By that I mean Trump is absolutely correct to identify and target the listless economy, this lingering depression, and declare that it is wholly unacceptable. This needs to be done and it is unambiguously positive that it is finally being done. Orthodox places like the Federal Reserve as well as the OECD have, recently coming to terms with the lost decade, instead given up completely on any sort of recovery not because they can explain it but rather because the only way to preserve Economics as it is today is to declare “this is just the way it is.”

I wrote back in September 2012 that:

Similarly, it seems very plausible that the appearance and persistence of high unemployment right now is the very visible sign of the asset inflation side of monetary imbalances, with one caveat: the unemployment part is not coincident to the inflation. The process of inflationary intrusion is essentially the same whether consumer or asset inflation: consumer inflation destroys purchasing power directly, while asset inflation destroys purchasing power eventually through price collapse (asset prices can no longer support debt levels, so the relative ability of real incomes to flow to discretionary funds is constrained or destroyed altogether). The end result is exactly the same but through different means and across different lags or timescales. Monetary imbalance, no matter what form, ends up in the same place.

That would seem to perfectly describe China (and a great deal else) post-2012. There is and has been only one currency war – the “dollar” with itself, both on the way up and now on the way out. Its demise would be cause for celebration if the world were at all ready for it; it is not. Political fixes are inherently messy and often strung out affairs by their nature. That is often because politicians focus on symptoms rather than carefully identifying and understanding causes. Attributing our current state to China’s entry into the WTO, indeed its currency “devaluation” since the start of 2014, is all post hoc ergo propter hoc fallacy. The problem is certainly offshore and anyone is right to finally look in that direction, but “dollars” preceding jobs.

Stay In Touch