Why did Mario Draghi appeal to NIRP in June 2014? After all, expectations at the time were for a strengthening recovery not just in Europe but all over the world. There were some concerns lingering over currency “irregularities” in 2013 but primarily related to EM’s and not the EU which had emerged from re-recession. The consensus at that time was full recovery not additional “stimulus.” From Bloomberg in January 2014:

Among countries using the euro, economic confidence rose in December to a 2 1/2-year high after an 18-month recession ended in the second quarter.

It was common to find survey data in particular reflecting the economic possibilities of 2011 or 2010. Not only was growth apparently accelerating it was, at least expressed in the mainstream, broad-based. From Bloomberg in September 2013 with regard to China:

“Growth in China has seemingly already passed the trough and looks set to recover further in the second half,” the OECD said.

From Bloomberg in December 2013 relating mainstream US economic predictions:

“This economy is getting ready to kick it up a notch,” said Chris Rupkey, chief financial economist at Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi UFJ Ltd. in New York, who correctly forecast the orders gain. “Consumers are feeling confident enough to buy the biggest of big-ticket items, the family home, and companies are seeing enough demand to buy equipment at close to record levels.”

From the consensus view of the global what the ECB did in the middle of 2014 doesn’t appear to make much sense, particularly when compared to the Federal Reserve that had shifted its narrative toward “overheating.” Why the additional European “stimulus” at that time? And why was it NIRP first rather than full QE or even other QE-like programs?

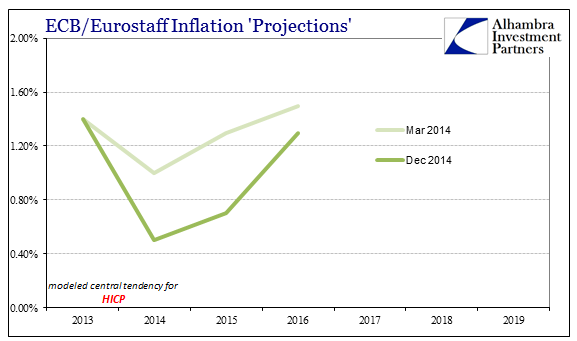

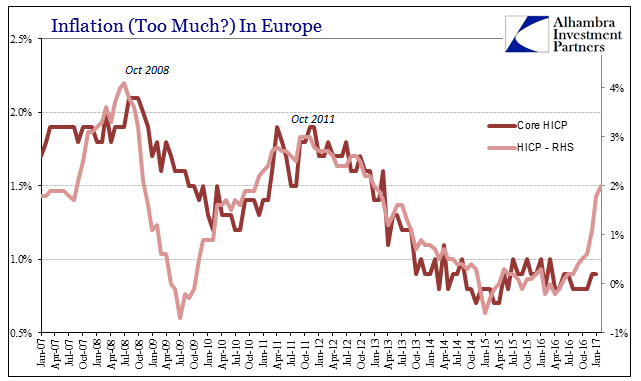

The answer to both questions was inflation. Despite uniform and ubiquitous predictions for a strengthening, confident recovery the Continent’s HICP was set to decelerate against them. From an already low level, it was just 1.4% in 2013, Europe’s central bank feared too little margin in consumer prices when in March 2014 the ECB staff projected just 1.0% inflation for calendar year 2014.

Not wanting to risk a fall below that level, the ECB decided it had to act. Though they may have preferred QE right from the start, they hesitated to go that route because of bond rates. Recognizing that interest rates are not always the “stimulus” they are claimed to be, a large program specifically buying more sovereign debt threatened to make the inflation problem, from the perspective of policymakers, worse.

Instead, they thought NIRP would help as a gentle nudge for banks to mobilize some of the useless bank reserves. The expected increase in bank lending could then work with the bond market to transmit inflation expectations without the fetter of ECB purchases and what economists believe is their effect on interest rates (they think them lower due to monetary policy). It was supposed to result in the best of all worlds, the broad-based recovery with inflation expectations and then inflation itself confirming it.

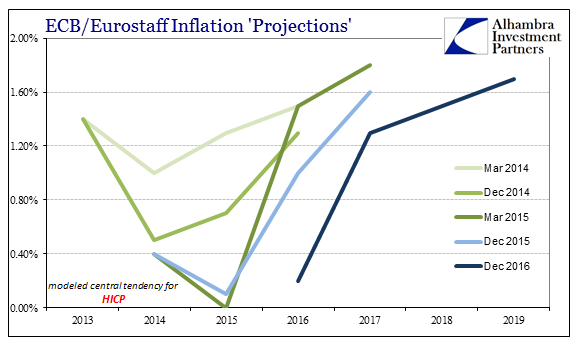

Unfortunately because orthodox Economics is predicated on such a small knowledge base of mostly past correlations, almost nothing went right from the moment the ECB acted. Inflation only continued to fall, as did bond rates anyway, and by the end of 2014 even the idea of recovery was being rethought (though reluctantly and only as a small probability at first).

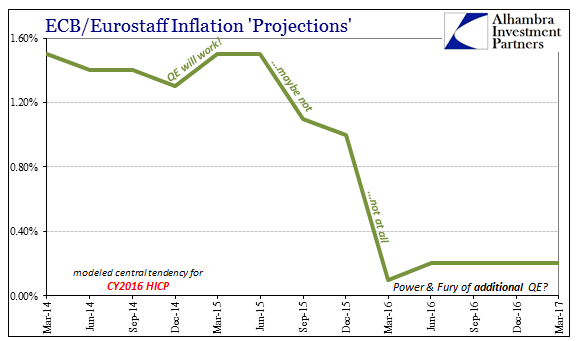

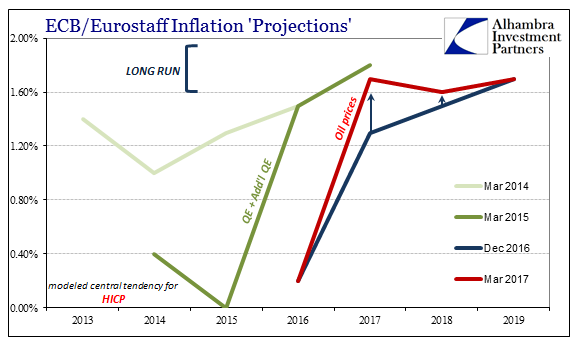

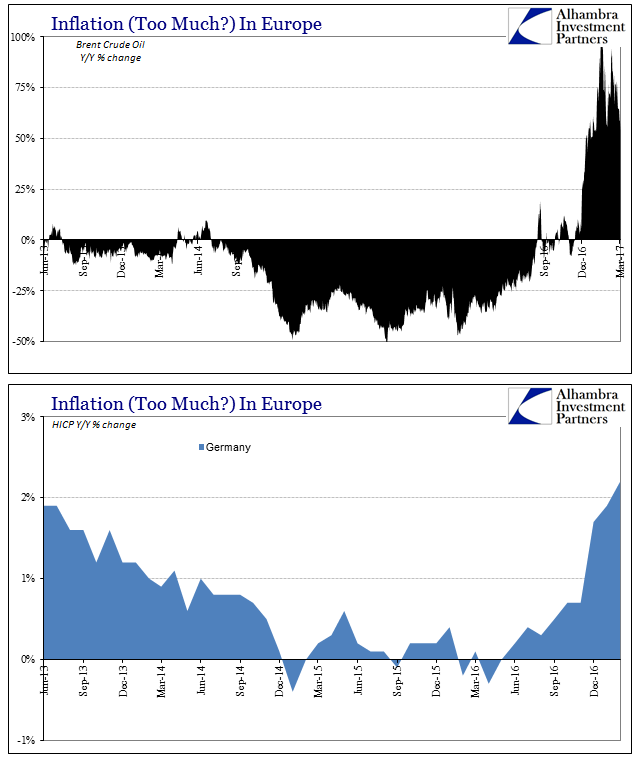

The ECB ended up doing QE after all in March 2015, and then even adding to it. From the perspective of the HICP inflation rate, there was no detectible influence from anything the ECB did or threatened to do – including deeper NIRP. In fact, it wasn’t until the oil price rebound late last year that inflation actually performed as it was supposed to. In other words, it was Brent that has pushed the HICP and not QE or recovery for that matter.

But oil prices are not more than a temporary boost to inflation, and thus the overall confidence that this time will be different than 2014. You can see it in the different projections December 2016 to March 2017. Inflation is following overall the baseline recovery from last year with a sharp oil price effect that is forecast to continue next year tapering off somewhat. That means these projections count not €48 or €54 but continually rising oil to match the assumed broad-based firming for all of 2017 and beyond.

But as oil prices fade in acceleration past some point, the ECB and Eurostaff are figuring that Europe will simply follow the 2014 model just three years delayed and oil price distorted. They are still looking for inflation to normalize even though there isn’t yet any indication that is happening.

That means we are left with another prospective disappointment on the inflation front as the oil base effects diminish and do so faster with lower oil (relative to earlier this year). Economists in Europe are predicting that inflation will peak in Q1, as it surely will, but then moderate by a small degree for the rest of this year: from HICP 2.2% in the first quarter of 2017, then 1.8%, 1.7%, and 1.6%, in the next three quarters, respectively.

Unless Brent prices rise not just back to €54 but further than that, again Europe is going to be undershooting and maybe considerably on consumer prices (which is a small bit of good news for consumers; bad news for the ECB). And with the loss of “firming” expectations for HICP, the “reflation” trades taking place all over the world it will in all likelihood translate into disappointment of the 2014 variety all over again.

That answers the latest ECB policy question about why they are in no apparent rush to end QE after being so reluctant to start it. The risks to inflation, like in 2014, are all on the downside and to a degree considerably greater than are either forecast or talked about in public. Privately, of course, policymakers are continuing forward with what has been the real strategy almost from August 9, 2007 – fingers crossed that it just all somehow works and goes right for once, even if they have no idea how or why. Why should that last part change regardless of oil?

Forecast recoveries never make it past the forecasts because there is no recovery. These cycles of inflation disappointment continue because nothing has really changed except the level and timing of predictions. HICP calculations for March are due on Friday, and are already expected to show the first deceleration in a year.

Stay In Touch