When Apple introduced the first iPhone in January 2007, the 8 gig model retailed for $599. The company cut the price to $399 that September in an alliance with AT&T. The 8 gig iPhone 3G that debuted in July 2008, just eighteen months later, was set at $199, and less than a year after that was suggested to retail at a mere $99. By September 2014, you could get the latest 128GB iPhone 6 Plus from AT&T that cost $100 less than the original iPhone 1 with its 8. And for what it’s worth, an original first gen iPhone 4 gig mint-in-box was listed for $15,000 that same year.

Prices are funny things, and damn far from predictable. They are a good part, if not the full part, of Adam Smith’s invisible hand. Companies don’t just pick numbers at random and start retailing, of course, but they don’t often know what the price of something “should” be, either. That is true even if it is a product they invented and for a time they alone sell. The natural processes of innovation and capitalism produce deflationary pressures, a fact that no economist can contest.

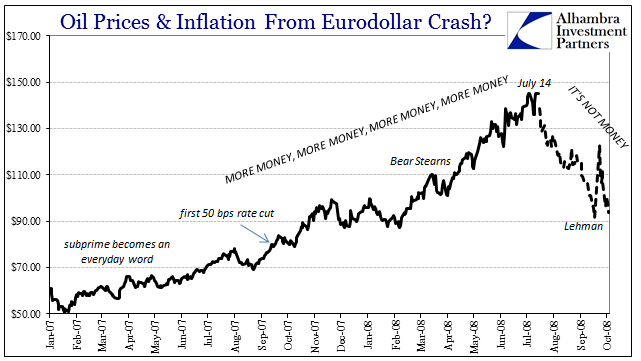

Yet, the Federal Reserve and indeed all central banks are committed to a regime of price stability. At least that is what they call it, for in truth it isn’t that nor is that really why they do it. They seek to control variation for the simple idea that variation is somehow exclusively bad. If oil prices rise to $145 as they did in the middle of 2008, what did that tell us about either monetary policy or the state of the world in an inflationary context? As we found out later in July 2008, absolutely nothing of use.

If the price of oil should rise to that level again, who should say that isn’t the “correct” price of oil? If the Fed were to follow its directive to the minute detail, a policy-mandated low price of oil might result in a consumer paradise, but it could just as well end up with an economy like Venezuela. How do officials separate the monetary from the capitalism?

After all, as Milton Friedman showed, inflation is by definition a monetary phenomenon. The truth of the matter is far more mundane and simplistic – central bankers make no attempt whatsoever to sort out useful, productive deflation from money-driven inflation. They don’t even define price stability for the reasons you might think. The common 2% inflation target is merely the level that economists have judged as a sufficient buffer so as to be able to avoid another 1929. Yes, modern price targets are stuck in the 1930’s.

Commitment to price stability is really a commitment to distortion. Period. The fact that you claim that you let markets work out how that 2% “stability” is to be distributed is not an argument but rather avoiding the necessary act of justifying the target. If Apple is unbelievably successful in innovation as well as productively bringing its products to market so as to spark a systemic deflation of broad-based rising living standards, why should the Fed seek to offset, or let the private monetary system itself offset, lower prices with money-driven inflation?

When Irving Fisher first worked out his version of quantity theory of money, he included “T” where now stands the variable for national income or output (y); which used to be more generically Q. This is not to say that the equation of exchange is a useful model for predicting economic variables, but it is a useful mode of conception for thinking about how money and the circulation of money can be non-neutral. If there has been a considerable amount of productive deflation, such as in the 1980’s and 1990’s, the central bank might “allow” a buildup of monetary forces through the whole range of activities described by the more comprehensive “T” rather than only those in “y”; which is the only variable it actually monitors.

In October 2002, near the bottom of what was the dot-com bust, and almost a year after the official end of the recession caused by that bust, Ben Bernanke spoke to an audience in New York on the topical topic of asset bubbles and monetary policy. To save you the time of having to read his hastily gathered thoughts, the short version is that according to Bernanke central banks can’t identify bubbles and even if they could monetary policy isn’t the right tool to do something about them.

Let me discuss the two parts of this recommendation in a bit more detail. The first part of the prescription implies that the Fed should use monetary policy to target the economy, not the asset markets. As I will argue today, I think for the Fed to be an “arbiter of security speculation or values” is neither desirable nor feasible.1 Of course, to do its job the Fed must monitor financial markets intensively and continuously. The financial markets are vital components of the economic machinery. Moreover, asset prices contain an enormous amount of useful and timely information about developments in the broader economy, information that should certainly be taken into account in the setting of monetary policy. For example, to the extent that a stock-market boom causes, or simply forecasts, sharply higher spending on consumer goods and new capital, it may indicate incipient inflationary pressures. Policy tightening might therefore be called for–but to contain the incipient inflation not to arrest the stock-market boom per se.

This view very clearly separates asset price inflation, which the Fed does not consider, from consumer price inflation, which it obviously does. Bernanke’s argument was structured around the narrow topic of identifying asset bubbles, a notoriously difficult job especially in getting at them early enough before they become like the dot-coms or the concurrent housing malformation. On that point he was and probably still is correct, for the last thing we would ever want is for the Fed or Economists to define price stability in asset markets.

So why should we then permit them to do the same thing for consumer prices? Any economist will answer that there are more direct and studied relationships with consumer prices and economy than asset prices and economy, but that is again missing the point. Just because economists have studied consumer prices as an aggregate variable doesn’t mean they any more understand them, nor is it truly clear why they would.

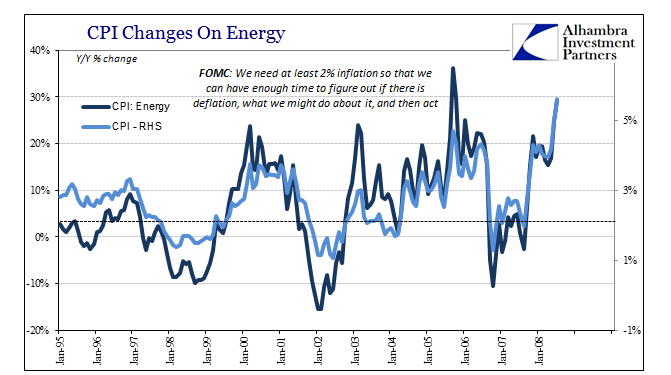

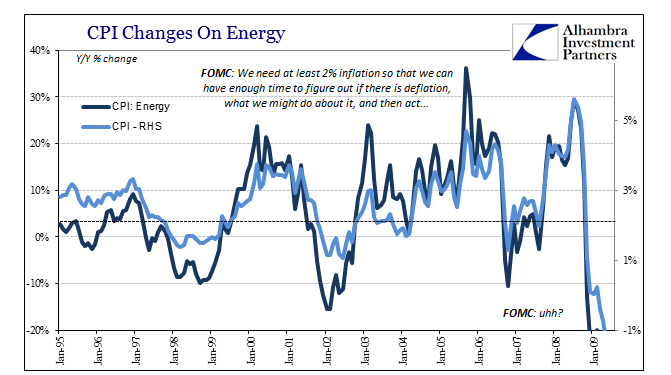

By targeting (or claiming to, actually hitting and maintaining that target has proven to be another matter altogether) 2% for consumer prices, central banks have already declared themselves on the side of inflation, for again one reason alone in that they believe that level of price increases is high enough to permit them the time by which to forestall monetary deflation, their worst of worst cases. But maybe that isn’t true, either:

Perhaps the fact that policymakers have no idea what they are doing is more germane to all these parts and discussions. That was surely the case on full display in 2008, where a nearly 6% CPI was nowhere near enough “cushion” for the Fed to get its act together and prevent the impossible from occurring. Even the markets were given an up close and all-too-personal lesson in functional monetary policy.

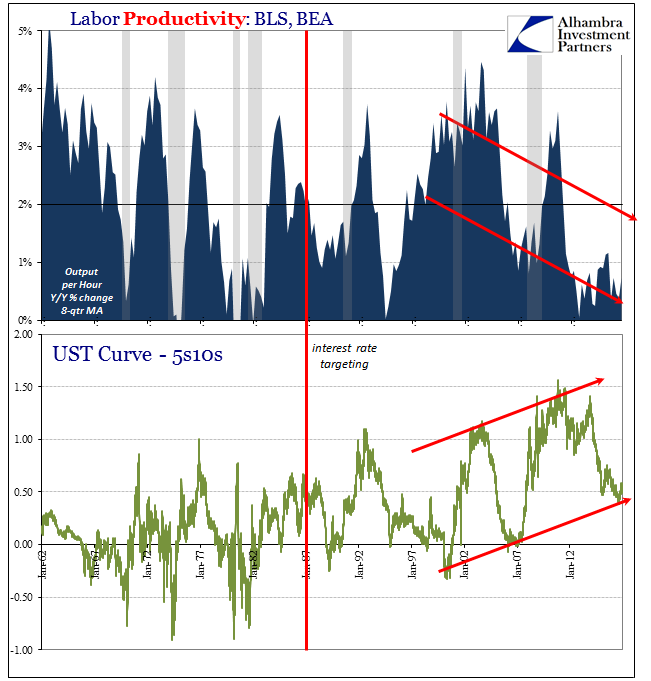

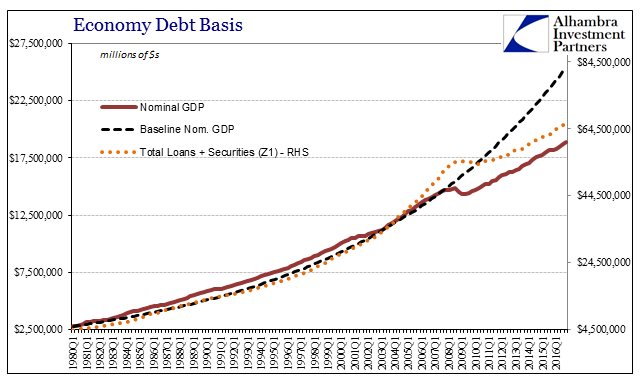

Again, commitment to price stability is commitment to distortion, and in the later 20th century/early 21st such things are quite easy to spot. From almost the moment the Fed switched to interest rate targeting rather than money supply targeting (which, by virtue of the Great Inflation, they were incompetent at, too) distortion in “T” is all we find.

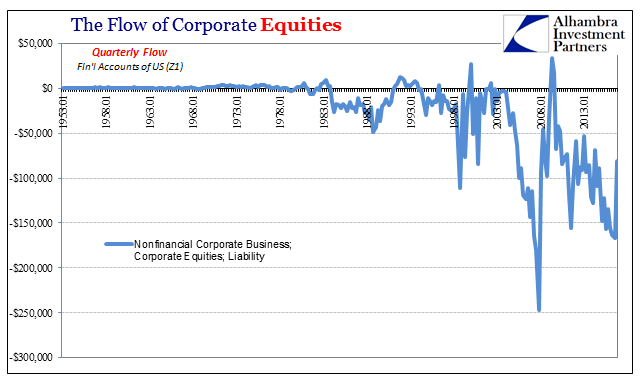

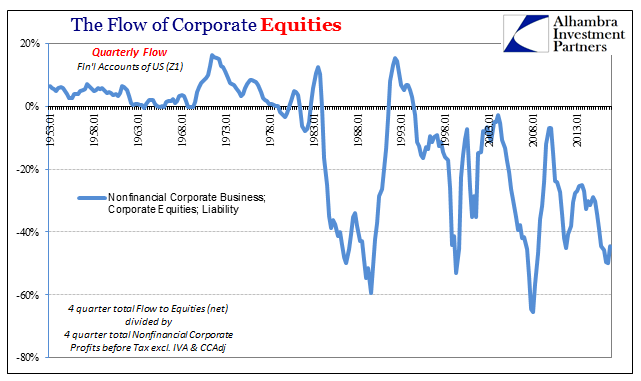

The Federal Reserve’s Z1 statistics provide one estimate for corporate (non-financial) equity repurchase activity. A negative number is the retirement of shares, whereas a positive number is what the textbooks say stock markets do for the economy, which is supposed to be the raising of funds vital to economic investment and therefore the very baseline potential. Since the early 1980’s, unsurprisingly, the number has been for the first time consistently negative. Adjusting for some kind of scale, in this case (below) total flow buying back stock as a percent of total before tax profits, we find that monetary distortion through this channel has become a constant feature.

Outside of recessions, US corporations have been drawn to share repurchases over the past thirty years in a way they never were before (they were, in fact, practically unheard of before the 1980’s outside of the relatively rare private equity transactions). There is no particular reason why this behavior should be harmful on its own, and we certainly do not need nor want any government agency deciding when or if it is. But in the case of especially the 21st century economy, it becomes clear that this is a big and destructive distortion made so by the manner of eurodollar redistribution.

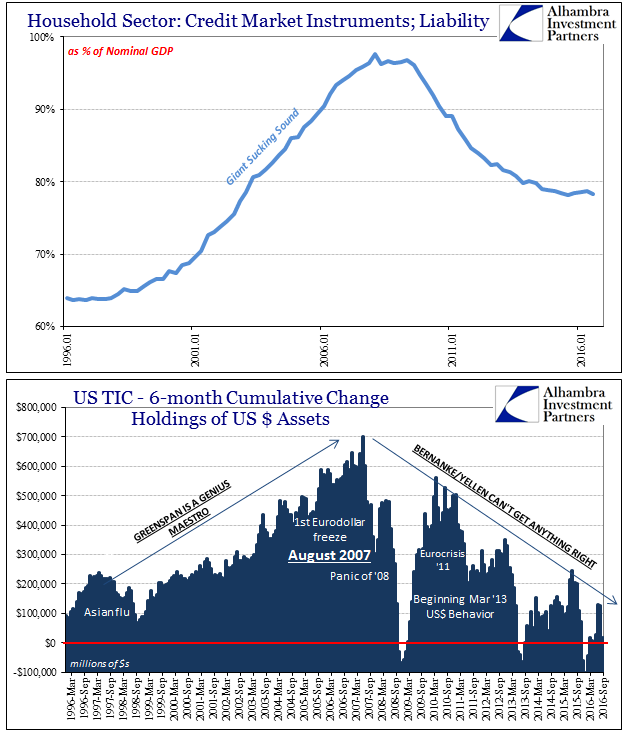

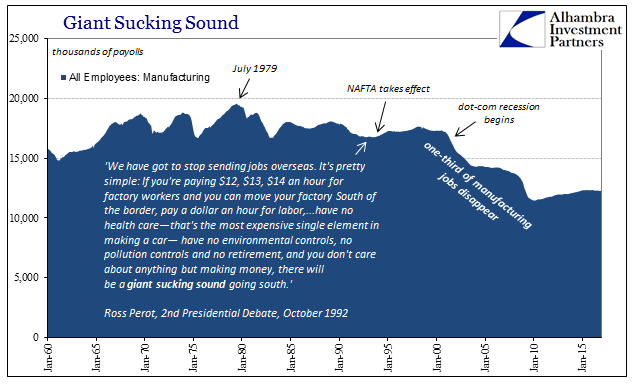

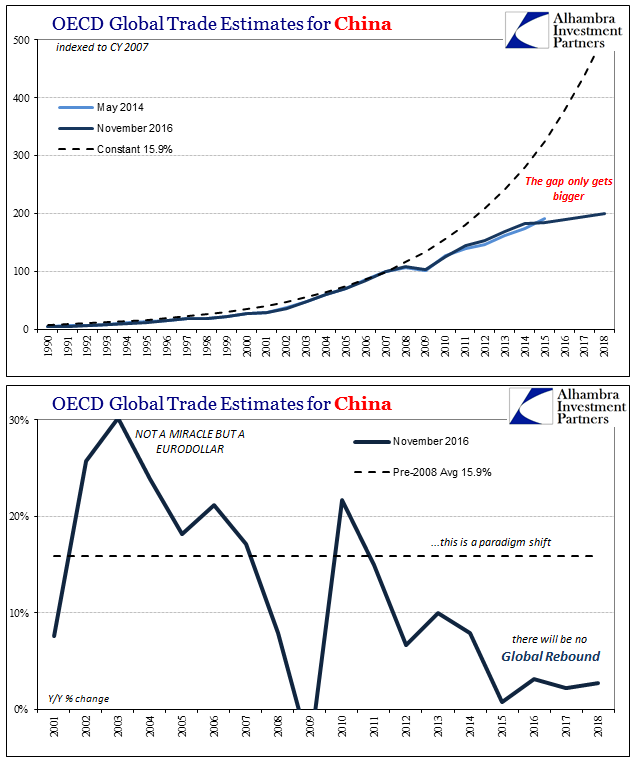

Around the time of the dot-com bubble, global monetary finance changed radically from a system intended to give and distribute resources for the purposes of ordinary trade to one that was a complete and parallel offshore money and banking system feeding volume at all considerations. In terms of its effects, US corporations invested productively offshore where the eurodollar debt binge led them to cheap labor. Given that capex was taken in that overseas direction, what was left for US companies to do inside the US? Buy back stock more exclusively (somewhat hyberbole), and especially after 1998.

We find this very transition right where you would expect to:

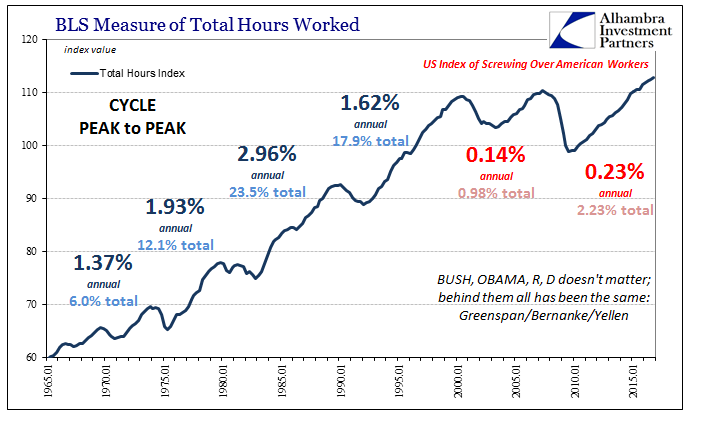

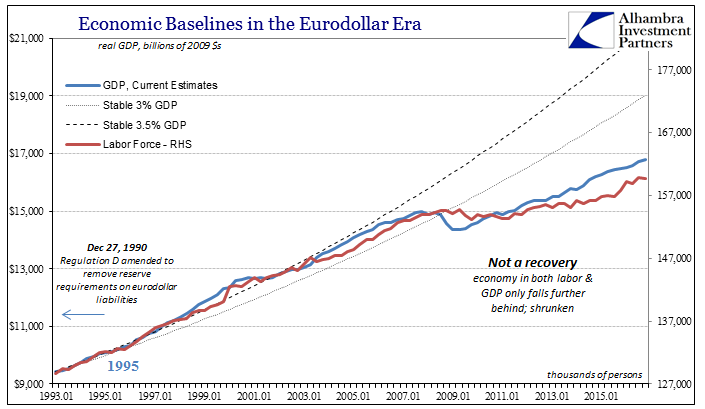

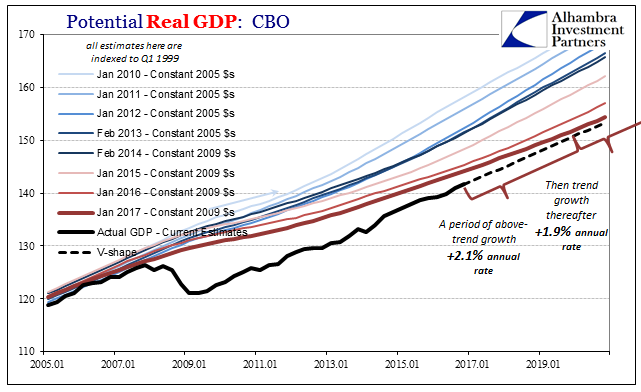

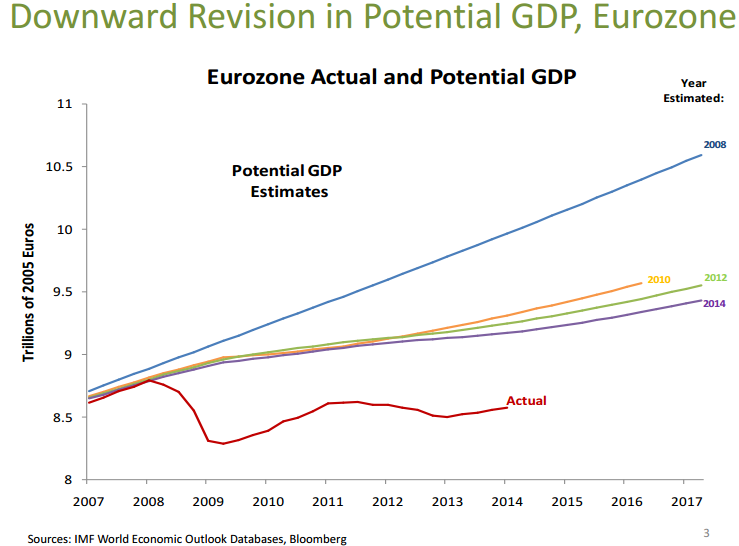

Once the burst of productivity due to the dot-com bubble itself started to wear off by the time Bernanke was talking about asset bubbles, the “new plateau of prosperity” that Fed officials were sure was happening as a result of their own policies throughout the 1990’s disappeared with pets.com. Without onshore capex as opposed to onshore buybacks, the results were initially less labor but at first supplemented with debt before giving way after the Great “Recession” to just less labor.

By focusing on consumer prices alone, the Fed had no idea any of this was happening. If they had been forced into monetary competence, by statute or just sheer dedication to duty, they might have at least become aware that the eurodollar system had distorted a great many things far outside of the CPI. Monetary officials still have no idea even now all these years and decades later what happened, as Fed Vice Chairman Stanley Fischer “testified” today, at least to Steve Liesman of CNBC:

That’s what everybody would like to see and you can see some elements through fiscal policy, but the really big factor underlying growth is productivity growth and it’s been very likely the reasons are not fully understood. They are big arguments about whether we mismeasure it and so forth, but we’re looking recently rates of productivity growth of 1% a little bit higher, and sometimes less for a few years. So that’s very low by historical standards. It could be higher if there’s a burst of inventions that generate employment as well as enjoyment. And there are possibilities of people changing their minds about investment. The rate of investment is very low in the economy at present. [emphasis added]

These are not, by far, our “best and brightest”, for they actually thought that by moving the federal funds rate around a quarter point at a time they could achieve sustained 2% inflation which was equivalent to but one view of price stability as if that was something positive that should always happen. It’s a stack of assumptions upon assumptions upon assumptions that individually never pass the smell test. Had the Fed been made to focus instead on a stable dollar, not prices, they would have been forced to reckon with the world as it was becoming while it was becoming this way.

At this point it is a waste of our time and effort to try and bring them up to speed. For one thing, Bernanke already pinpointed the primary problem in another speech he gave in 2004 when talking about, you guessed it, the Great Depression:

Countries on the gold standard were often forced to contract their money supplies because of policy developments in other countries, not because of domestic events. The fact that these contractions in money supplies were invariably followed by declines in output and prices suggests that money was more a cause than an effect of the economic collapse in those countries.

Substitute above “eurodollar” for “gold” and “offshore” for “in other countries” and you’ve got the whole of the Great “Recession” explained, right down to the revelation by economic potential of what happens for changes in productivity and corporate investment related to offshore and eurodollar.

Stay In Touch