We had become either sensitive or desensitized, depending on your definitions, to quarter ends full of turmoil and intrigue. In the monetary world, especially last year, each of the four seemed more interesting than the one preceding it – which was saying something given the state of the world during that time. Most of all, however, it was especially striking that while all this was going on the mainstream did its best to describe all of it in a way that made it seem nothing was going on at all.

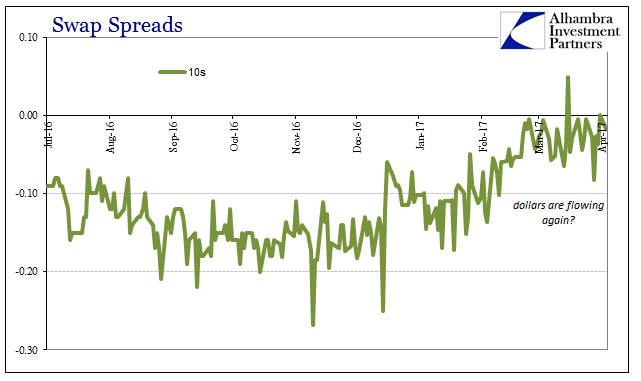

The end of the first quarter of 2017 has been the first to truly live up to that characterization. There was practically nothing of notice to report, at least on the negative side, other than the usual imbalances (even the 4-week bill rate was but 1 bp below RRP). There were quite a few attenuated indications, including a 10-year swap spread that touched zero for the second time in a week.

By outward, recent appearance that seems to be a very big deal. It has been derivative prices that have for the past few years of the “rising dollar”, “dollar shortage”, or whatever euphemism you might come up with to describe the global eurodollar instability since 2014, that have indicated the primary problem with all of it – the lack of balance sheet capacity distorting a great many things. A negative swap spread, as a hugely and persistently negative basis spread, is an offense to basic financial logic as well as one cherished orthodox law. It is in the purest of terms a meaningless result, a category error, for the market is not claiming that financial counterparties are less risky than the US government.

A negative swap spread tells us nothing other than the system itself is upside down. In the case of the 10-year swap spread it had become very negative, at one point in November on the day after the US election nearly touching -30 bps. With it back at zero, surely that must mean all is well and right again?

That is the interpretation the few who actually follow such things are quite predictably starting toward. The Wall Street Journal published an article yesterday claiming that very thing, or to be fair “almost” that very thing. The headline was pretty much all you needed to know: Hurrah, Dollars Are Now Flowing (Almost) Normally Again.

But the flow of dollars around the system is working better elsewhere, too. The cross-currency basis against euros has also almost halved, taking it back to where it was a year ago. The extra cost over Treasury yields of swapping fixed for floating interest rates — used for hundreds of billions of dollars of corporate deals a year and known as the swap spread — is almost back to normal after two years of being deeply negative. Even the willingness of banks to lend to each other has improved: the spread between Libor borrowing costs and risk-free overnight indexed swaps has halved from its August peak.

All this fits with anecdotal evidence of investment banks loosening the purse strings and becoming more willing to lend to clients. “I have banks calling up and saying they’re going to allocate me more balance sheet,” said one big fixed-income investor.

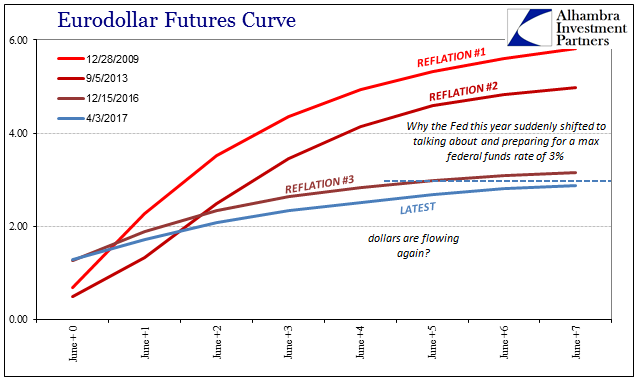

Like the economy, there is no arguing the relative improvement in conditions this year as compared to last or the last two. After all, fourteen months ago the world’s financial markets were swept up in violent liquidations where the words “global turmoil” were the active ingredient in monetary policy settings all around the globe. There is no denying the “reflation” wave that began in late 2016, but that doesn’t necessarily mean an inflection. Is the Journal also making a category error?

From the narrow perspective of just the past few months, it doesn’t seem that way. As with basis swaps in several currencies, there has been notable improvement. But “improvement” is not a universal term, and as with all things where the “dollar” is concerned it requires serious breadth of coverage in order to more properly analyze. According to the narrowest sense, what you see above, there is indicated better “dollar” conditions and balance sheet capacity as compared to most or all of last year.

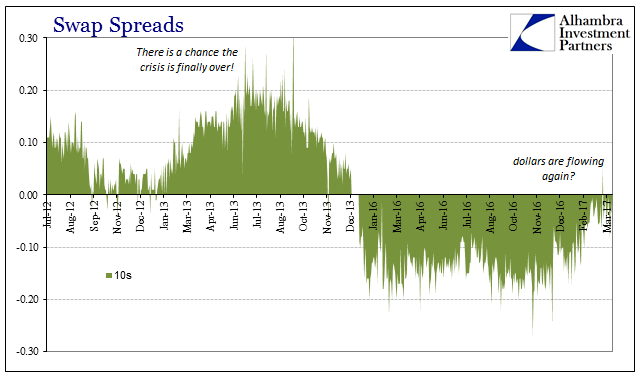

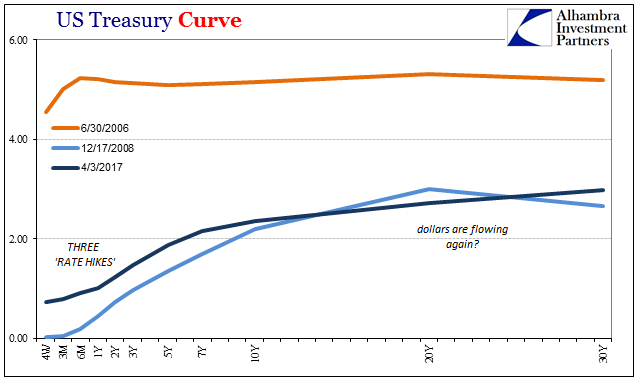

As usual, however, being better than really bad doesn’t often add up to good, or in the Journal’s assertion “almost” good. When comparing this progress in terms of the 10s to 2013, for example, and the very similar “reflation” trades of that time there is clearly much less enthusiasm still.

This is the appropriate starting point for monetary and balance sheet analysis, because it was in the middle of 2013 where the same sorts of “expert” opinions made the same sorts of pronouncements. In the current case, the Journal, as do many others who think like it, ascribes monetary improvement in 2017 to the possible repeal of Dodd-Frank, the Volcker Rule, or just a general sense of how things are surely going to be better.

Dollars shortages are now going away, helped by expectations that U.S. regulation will be relaxed, the success of overseas banks in finding alternative sources of finance and greater appetite from investors to pick up what looks like free money left lying around by the global financial system.

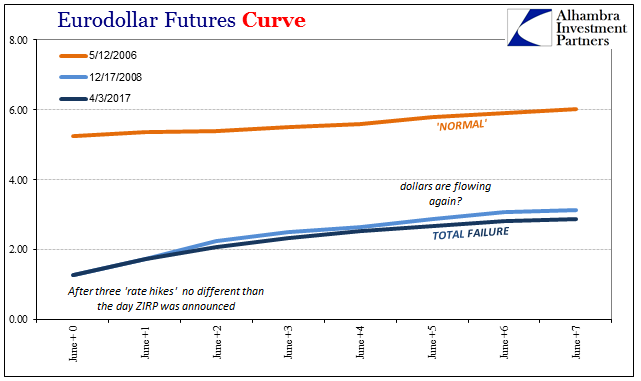

In 2013, the same sentiments were expressed only with QE3 in mind rather than regulations. It was only after the events of later 2014 forward completely and utterly surprised these mainstream opinions that it was after-the-fact decided regulations just had to be to blame. Even if we assume that was and is the case, the relative comparison of swap spreads (or UST yields, eurodollar futures, etc.) then versus now shows a very different interpretation than a return of dollar flow. Markets were much more excited and indicative of a that four years ago versus now, and given that turned out to be a false assertion, what does that say about the same one being prepared all over again?

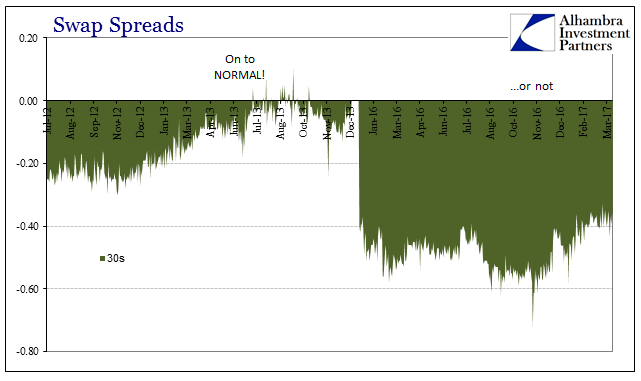

For one, it was the 30-year swap spread that turned positive if only briefly in the summer of 2013. Almost four years later, the 30s have like the 10s improved but only in comparison to last year; they are still highly negative.

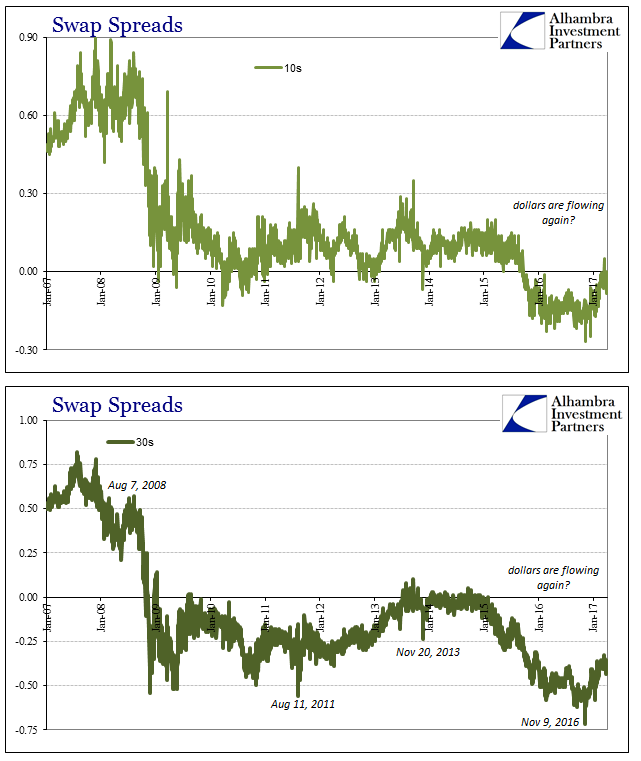

In many ways, though, we are simply splitting hairs, debating the volume of “dollar” flow from one less bad era to the next. An actual return of “dollars” and balance sheet capacity would mean normalcy, not the possible switching of signs positive to negative back to positive again. It is entirely human to assign a great deal of importance to round numbers and even levels; in this case even more so given the nature of a positive swap spread as different from a negative one. In the broader context of “normal”, the actual basis for all subsequent interpretation becomes very clear:

The swap market shows us that we are, in fact, nowhere near normal or even the slightest hint of it. What we are witnessing is the same phenomenon as 2013, and less so, where relative progress is mistaken for, and emphasized as, a meaningful change – a category error that is either intentional or drawn from ignorance. It should be perfectly clear that the word improvement as it relates to 2017 only applies to the conditions of 2016, and nothing more than that.

No financial episode or trend ever moves in a straight line, and this complete monetary history shows us that case playing out across years and several instances. Even the 2008 crisis was not a single one but three, with what appeared to be significant “improvement” especially after the first (up to Bear Stearns) and before the second (July 2008 to Lehman and the initial panic). The baseline of “dollar” problems remains firmly intact, stretching all the way back to August 9, 2007, an unfortunate result that wishing it away each time this happens does us no good, and only wastes more time as urgency is by the mainstream urged back into apathy.

This is, in fact, the worst case because of articles like this which seek to alleviate all interest in the very problem locking the global economy in its dangerous condition. I wrote back in January anticipating this very declaration, which wasn’t especially insightful on my part as I was merely restating the pattern that had already played out several times.

The big problem with these cyclical upturns (depression cycle, not business cycle) is these positive interpretations. It will likely end up being hugely counterproductive (if it continues for long enough) in the same way as 2013-14 was attributed to QE3 and the belief that recovery was at that time not just possible but even likely (it’s amazing in review how in late 2014 the Federal Reserve was more concerned about “overheating” and how that view pervaded, uncritically, the whole mainstream description of what was going on). With that conventional perspective, there was and will likely be far less urgency to do what is necessary, even to (honestly) examine what it is that might be causing this sustained misery because there are seemingly plausible conditions (positive numbers) that suggest an end to the misery finally at hand. The economy ends up like a dog chasing its tail.

The 10-year swap spread is again zero; hurrah for it. To suggest it, or the others like it, heralds an end to the “dollar” issue is to help ensure instead the still unsolved “dollar” issue will last for at the very least one more monetary cycle.

Stay In Touch