As world “leaders” gathered in Davos in January 2016, they did so among financial turmoil that was creating more economic havoc than at any time since the Great “Recession.” Having seen especially US QE as the equivalent of money printing, their focus was drawn elsewhere to at least attempt an explanation for the contradiction. They initially settled on the Fed’s rate hike, where terminating “ultra-loose” policies was for them creating the explosive conditions.

The end of ultra-loose monetary policy and the divergence between central banks in the United States and Europe are contributing to recent volatility in financial markets, top bankers at the World Economic Forum in Davos said.

What I object to most is the continued use of such terms. Nobody ever challenges the assertion that money policy anywhere has been “ultra-loose.” If it had actually been that we would easily be able to find inarguable evidence for it; we find instead uniform, ubiquitous confirmation of the opposite condition.

It’s not as if this is something new, either. Central banks have been claiming one thing only for us to discover something else entirely for a very long time now. In Japan, the clock on wrongful terminology has been extended beyond a quarter-century and to BoJ’s half a quadrillion, and all without a single, slightest satisfactory result anywhere. And still monetary policy is talked about as if it was actually stimulus. These words are taken for granted, simply assumed by credentials alone.

The last ten years has allowed us only one silver lining, an extended catalog of irrefutable, empirical proof that these economists have no idea what they are doing. They continue to be able to do all of it, however, simply because the evidence is never presented in a media that is either corrupt or inept for failing to live up to reasonable editorial standards of logic and prudence.

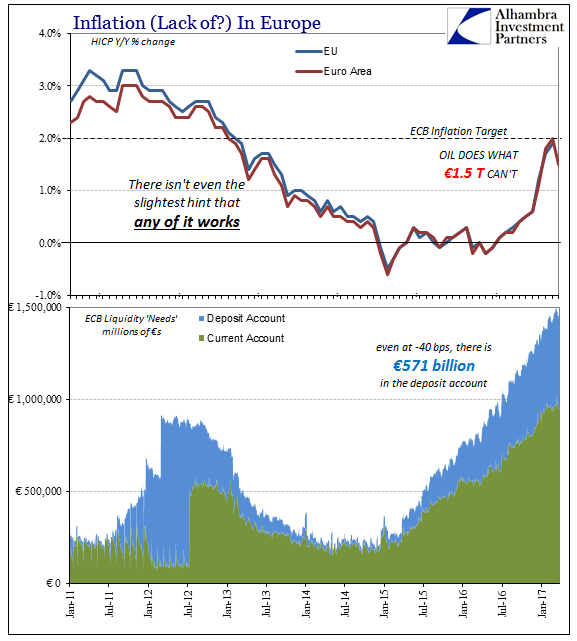

Take the latest example: Europe. Mario Draghi says today that the ECB should not be winding down QE just yet because more “stimulus” is called for. No one ever asks him, or any of the others, why more stimulus would be necessary years later if stimulus actually stimulated anything. It is the policy equivalent of spreading human excrement on a corn field, telling everyone that the crops are being properly fertilized, and then having the media continue to write about how you are enriching that field even as you continually pile on literal crap without the first hint of a green shoot.

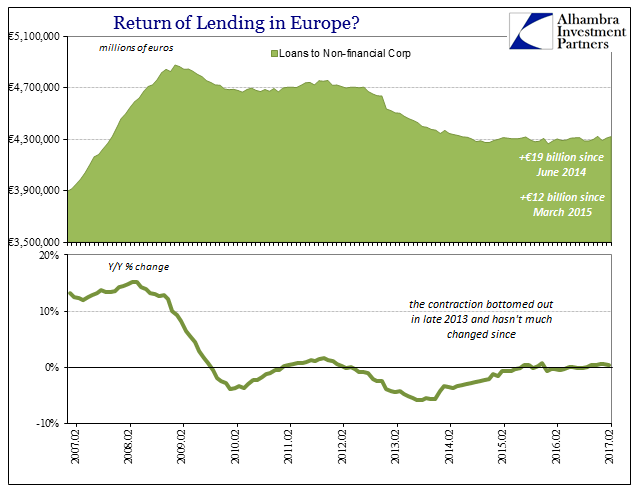

In May 2014, when confronted by a flagging inflation rate, the ECB decided it would first drop its money market floor (the deposit account) below zero and then if necessary provide some additional “stimulus” aimed at especially small and medium businesses (SME’s). It has been the business sector in Europe that has borne the brunt of the credit market retreat since 2008, and to truly get things going that sector would require more than any other stimulated credit growth.

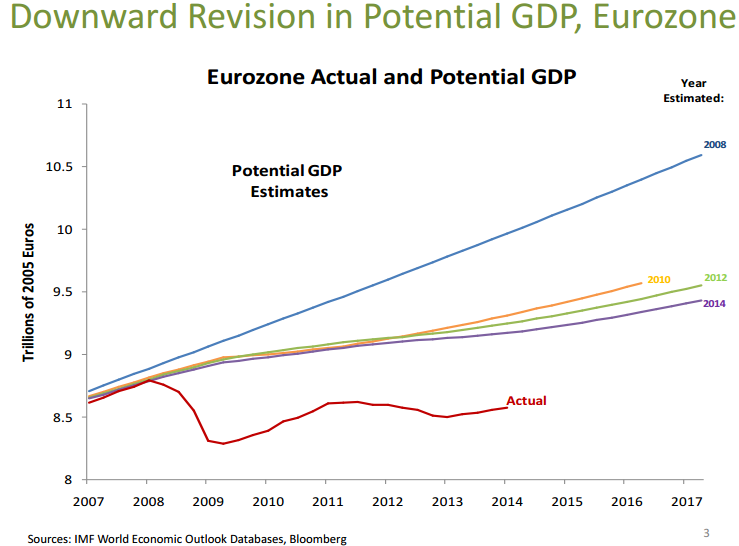

By September 2014, the Europe’s central bank voted for just that kind of “stimulus”, and in the two and a half years since loans to NFC’s (non-financial corporations) have grown by all of €32.6 billion; which means that loan growth has been completely absent. The ECB itself has bought almost four times as many corporate bonds in less than a year than loans to NFC’s have expanded in the nearly three years of NIRP.

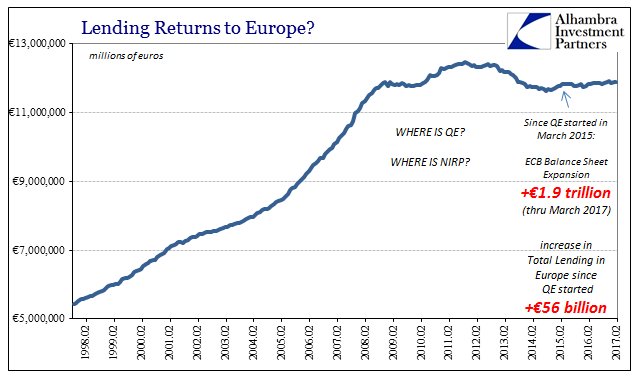

Total lending in Europe has barely budged, as well. Again, it is empirical proof that “stimulus” just isn’t and to a calendar length of more than sufficient time to establish it as such. The ECB has since the start of its QE in March 2015 expanded its balance sheet by just less than €2 trillion. During that time, total lending in Europe has increased by just a fraction of that total, €56 billion, which is overall a rounding error.

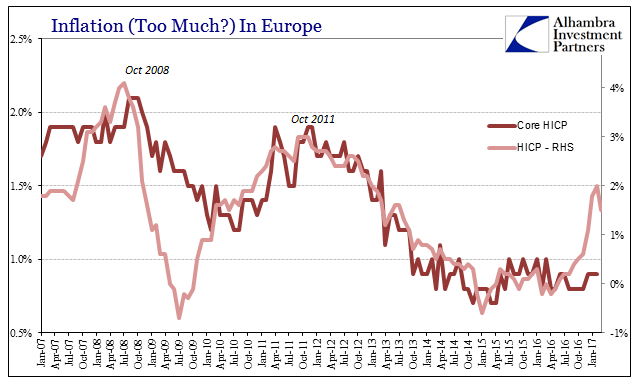

As noted prior, there has been absolutely no influence upon inflation that isn’t related to oil prices alone, due to the lack of follow through in credit markets.

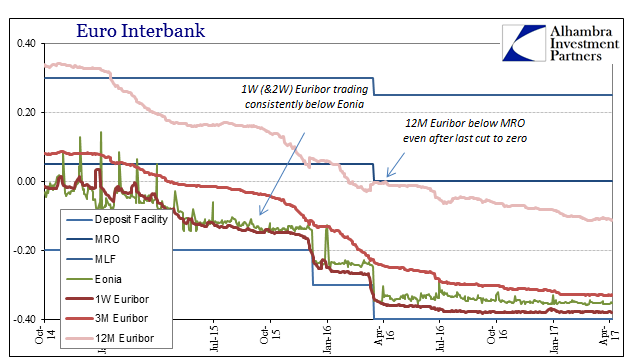

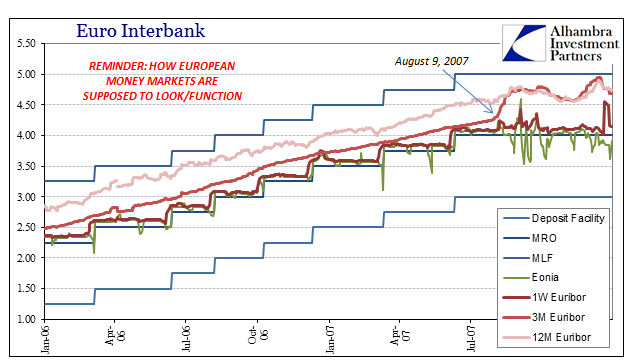

For all of this, European money markets are a disaster of blinding liquidity preferences that should be realized by these central bankers for what they say about conditions no amount of monetary policy will be able to change. Eonia, the overnight unsecured rate, continues to be hugely negative and way below the MRO, which used to be the secured floor for the main euro rates termed out from there. Now even term Euribor out to the 1-month maturity “yields” more negative than the overnight rate, and 12-month Euribor has not only fallen below the MRO but is now trading at less than -10 bps – the level the deposit rate started out below zero all the way back in mid-2014.

Banks are declaring in no uncertain terms that they will not part with the most liquid instruments, including government bonds at similar or worse negative “yields”, no matter how much the ECB might believe it is “stimulating” the economy by punishing them for doing that. Without bank acquiescence, meaning balance sheet capacity, whatever the ECB does is reduced to mere symbolism.

That established fact might let the media off on a technicality, though I have no doubt that is not what has been in mind when writing and speaking about “ultra-loose.” Again, there is absolutely no evidence that there has been “stimulus” in Europe, just as proof is lacking everywhere else in the world. The global economy, as the European economy, suffers for that because so long as in the mainstream these measures are treated as legitimate nothing will ever be done that could legitimately solve what is globally common affliction.

What we can say for sure is that monetary policy contains no money, and that central bankers don’t yet realize it even though it is their job to. Ultra-loose realistically applies only to the terminology used to describe this radical discrepancy.

Stay In Touch