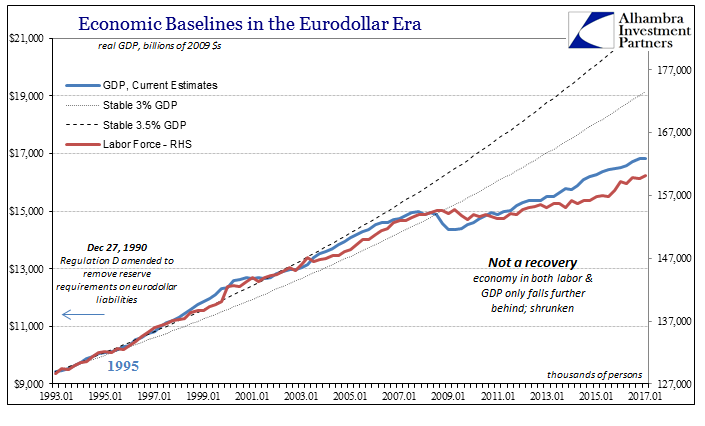

As I so often write, we still talk about 2008 because we aren’t yet done with 2008. It doesn’t seem possible to be stuck in a time warp of such immense proportions, but such are the mistakes of the last decade carrying with them just these kinds of enormous costs. It has been this way from the beginning, even before the beginning as if that was possible. The Great Financial Crisis has no official start date, but we know that it was February 2007 when it became mainstream news.

Before then, the bursting of the housing bubble was itself no sure thing, so neither was any economic fallout that might come from it. Some of the deeper financial elements, like ABX indices, derived from the most liquid traded of mortgage bond CDS products, were, however, screaming grave disorder from the get go. By and large, in late 2006, there wasn’t a great volume of distress signals but the quality of them should have been sufficient.

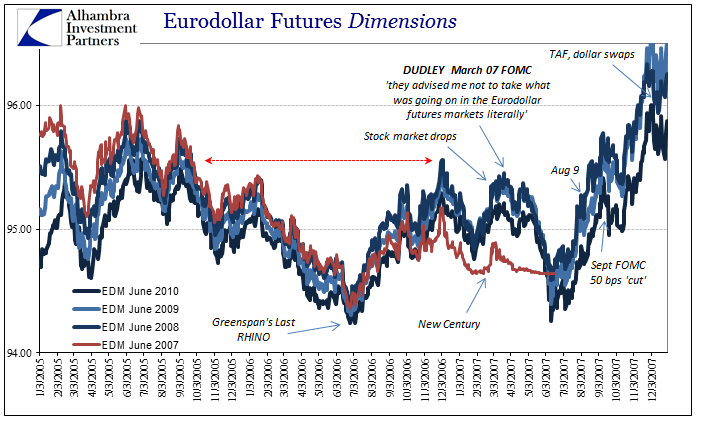

Outside of the ABX world, eurodollar futures were making similar noises. Because they were/are tied so directly to both real financial conditions as well as monetary policy, the Federal Reserve should have been fully prepared for all that came next. Instead, the FOMC’s persistent tendency throughout early 2007 was to respond with pure arrogance, just to ignore it all as if they knew better.

As I have written also before, the rationale for doing so was expressed several times in the official policy discussions of that year and by different individuals. Each time their argument boiled down to some variation of “the market has to be wrong.”

Dudley’s response was representative of the fundamental problem of orthodox monetary economics. “When people are in risk-reduction mode, they don’t want to take on more risk.” It was a tautology of a rationalization, if not complete circular logic, that there was no one on the other side of eurodollar futures to push them back in line with economists’ forecasts because anyone who might was reducing risk. If it was an arbitrage worth taking, there is no risk. What Dudley really meant, then, was what Lacker suggested before, “something limiting the capital.” He never answered Lacker’s question because he couldn’t; it might have looked to these economists as agents reducing risk, but functionally it was the same as reducing global, systemic liquidity, really money supply.

Reducing risk was just a euphemism the FOMC conjured to translate functional money contraction into their Fed-centric, 1950’s monetary worldview.

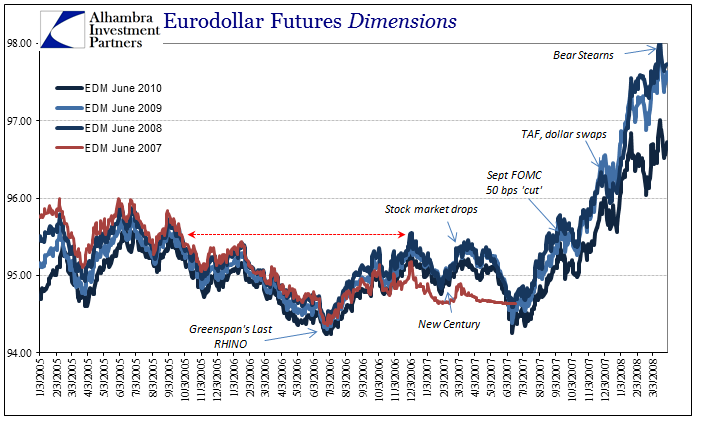

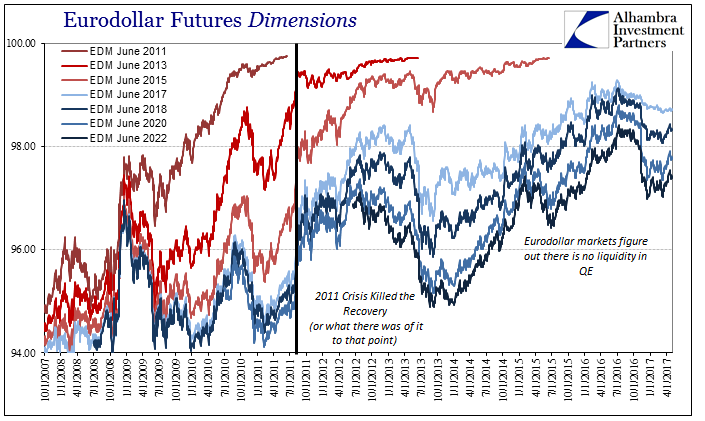

At each turning point during the crisis and even in the years after it, policymakers have demonstrated that the Economics they practice is ideology rather than science. Given so many opportunities to learn what they didn’t know and had wrong, which was, obviously, considerable, each every time they go back to 2007 and preach how the “market has to be wrong.” It was that way again in 2008 in the months before Lehman and then in the months after; in 2011, as despite two QE’s already in the books by then and $1.6 trillion in bank reserves created out of nothing, the FOMC was threatened by somehow a liquidity crisis of again global proportions to the point they actually debated bailing out the repo market.

The economic response each time is that it was no big deal, monetary policy was still effective just temporarily disabled by whatever the crisis of the day (as if they have all been unrelated and random fluctuations, externalities beyond human ability to realistically consider). Markets, however, never really shook off their 2007 doubts, so by 2011 they started trading for a desperately bleak future long before QE3 was ever considered, eurodollar futures most especially. And the official response was the same, “the market has to be wrong.”

But it wasn’t wrong, as eurodollar futures after 2011 described the world as it has become, unfortunately. Chicago Fed President Charles Evans did not attend those 2007 policy meetings, having been raised to the top regional job in September that year. But from his official biography as well as having been in that position through all that happened since you would think he would know better even though he never actually heard Bill Dudley’s infamous proclamation from August 7, 2007:

But it wasn’t wrong, as eurodollar futures after 2011 described the world as it has become, unfortunately. Chicago Fed President Charles Evans did not attend those 2007 policy meetings, having been raised to the top regional job in September that year. But from his official biography as well as having been in that position through all that happened since you would think he would know better even though he never actually heard Bill Dudley’s infamous proclamation from August 7, 2007:

MR. DUDLEY. As far as the issue of material nonpublic information that shows worse problems than are in the newspapers, I’m not sure exactly how to characterize that because I guess I wouldn’t know how to characterize how bad the newspapers think these problems are. [Laughter] We’ve done quite a bit of work trying to identify some of the funding questions surrounding Bear Stearns, Countrywide, and some of the commercial paper programs. There is some strain, but so far it looks as though nothing is really imminent in those areas. [emphasis added]

Just two days later, of course, the whole system stopped working and permanently so. As Northern Rock’s final CEO would later say, “the world stopped on August 9.” And it was Countrywide and Bear Stearns that contributed the fatal blows. The market has to be wrong?

Ten years later, heading into the summer of 2017, the world may at first seem to be in a different place, no longer so menaced by immediate crisis as it had been in 2007, 2008, 2010, 2011, 2013, 2014, 2015, and 2016. Yet, pessimism especially in eurodollar futures remains despite newfound and “hawkish” FOMC confidence. Policymakers proclaim themselves intent on “raising rates” as fast as they can, whereas eurodollar futures trade as if they don’t ever get very far. Charles Evans’ response:

I think that our path is more likely to be the one that we actually follow.

Or, as ZeroHedge put it, Fed’s Evans to Market: We Are Right and You Are Wrong. We live in a world of just these kinds of contradictions. After being on the wrong end of every one, policymakers remain steadfast anyway. Maybe it is just posturing for the cameras, assurances necessary, they believe, to keep up appearances just so the whole world doesn’t turn sour again too quickly. But I can’t ever give them that much credit, because their thinking infects so much more than just their own public speeches and recitations.

Since such tensions are normally correlated with overall economic conditions, it is unusual for social and political tensions to be so bad when overall economic and market conditions are so good.

That was Ray Dalio, founder of Bridgewater Associates, the world’s largest hedge fund, on Friday describing, for him, the confounding mix of social and political unrest “near their worst for the last number of decades.” From the view of eurodollar futures, there is no mystery whatsoever, leading one to question where Dalio might be getting “market conditions are so good.” That would seem only to apply to eurodollar futures traders who might have consistently bet against Charles Evans, Bill Dudley, and all the rest.

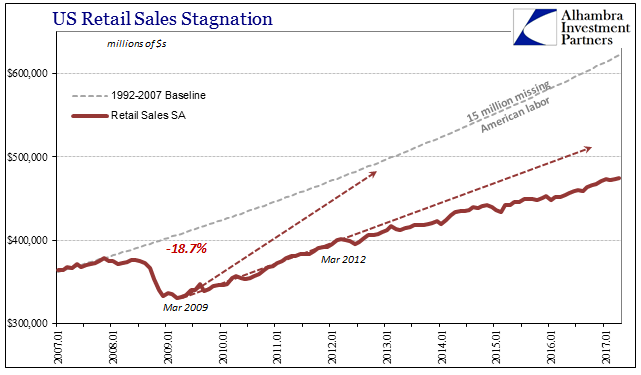

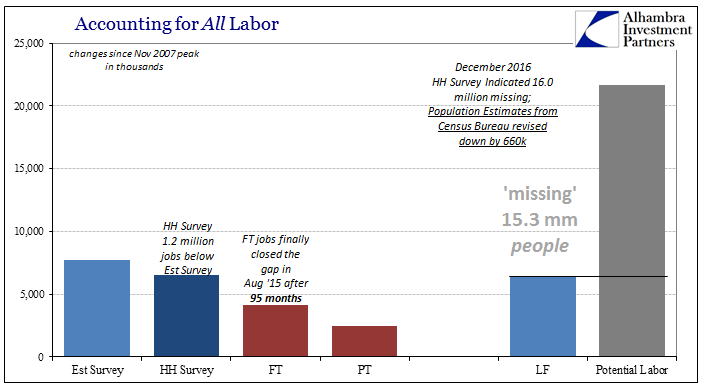

Growing social problems are very real and remain totally unchecked, as is the global economic depression that has provoked them. You can appreciate why it has been this way heading into a second decade. No matter what happens, the people most responsible keep trying to claim nothing really interesting happened. The world is in a good place right now even though it sure doesn’t look that way everywhere you look. Eurodollar futures aren’t the reason we aren’t done with 2008, but they have been right about it for more than six years now, and on off over the four years before that (especially, like 2007 and 2008, when it really mattered). Is it really time to start thinking otherwise? Why?

The burden of proof shifted long ago to Charles Evans and Janet Yellen, maybe even as early as the first few months of 2007. To answer the above question in the affirmative requires a lot more, a whole lot more, than the same “the market must be wrong.” Yet, despite all that has transpired, all that has gone wrong to the point of truly alarming circumstances in a lot of places, that is all there is upon which to base more optimistic assessments and expectations. It’s not nothing; it is less than that.

Stay In Touch