On December 3, 1999, Enron Communications announced that the company had begun operations selling bandwidth as an energy commodity. After publicizing the venture in May that year, it seemed natural given that they had been selling similar products in the energy sector, pioneering all sorts of products along the way. As the internet matured there was no way Enron would be left out of what was clearly going to be the future. The original product was DS-3 between New York and Los Angeles produced by Global Crossing, offering the blazing capacity of 45 megabits per second.

Enron’s President Jeff Skilling said, “This is Day One of a potentially enormous market.” It never really happened, though largely because carriers balked at the idea, preferring direct-to-customer and resisting the necessary standardization that treated all networks as equal. There were also questions about how serious the company was in offering the product, as in hindsight it appeared more as if Enron management in late 1999 just needed a story to tell Wall Street.

There is more truth to that than people know. In the movie “Smartest Guys in the Room”, the film spends, I think, too little time on what Enron called mark-to-market accounting. It was huge for them in allowing the business to expand throughout the 1990’s. It would become one primary element in the subprime disaster, but not as mark-to-market so much as gain-on-sale accounting.

A company’s financial statements follow specific rules so that investors or even just the Taxman can assess what you are on any given day. Gain-on-sale, however, is something totally different. It allows you to present financial strength based not on what you have received in the past all the way to the present, rather by what you expect to receive in the future and often far off in it. The key word in that sentence may seem to be future, but it is really “expect.”

The filmmakers managed to find a company video filmed as an almost spoof with Jeff Skilling playing himself. In it, Skilling describes being approved for what he comically terms Hypothetical Future Value accounting, which rather than being satire turned out to be the wave of the future. As his “character” says, “if we do that we can add a kazillion dollars to the bottom line.” They did.

Once you start getting into discounting of future values and cash flows, in areas like energy trading or even bandwidth there is almost nothing to go on except your own predictions. If you model X for that market and your take as Y, it doesn’t matter that X is unthinkably large and therefore Y sky high because there is no challenging the numbers. Enron had developed practically the only models and more importantly had built up a reputation that was seemingly unassailable. Why look behind their curtain because unless you were prepared to argue heteroscedasticity and Markov chains rather than transmission specs and pipelines you were at a fatal disadvantage.

The problem for the world in 2017 is not that Enron turned out to be a fraud, but that Enron turned out to be the leading edge. By that I don’t mean the wave of dot-coms that disappointed and flamed out. The future was the future, meaning money and math.

In truth, there wasn’t as much difference between LTCM and Enron as you may like. LTCM did what Enron did, only with much more discipline and rigidity. I don’t want to conflate Enron’s criminality with LTCM’s arrogance, as the two cases were not similar in that regard. The latter, though, depended upon statistical probabilities that gave it an off-balance sheet number that was in every way like money, and in that fashion LTCM and Enron were merely different points on the same spectrum.

If John Meriwether showed up at your door with his roster of mathematical giants including Myron Scholes and Robert Merton and said that his trade was going to do X dollars over its lifetime, nobody challenged the assertion. Not because they didn’t understand the trade, swaps were even by then a well-worn financial product. Where it really mattered, though, was in the statistical processes whereby LTCM’s numbers arrived at that present value of expected future cash flows. That part nobody in 1995 understood outside of a few who were at that time prevented from replicating them.

How does it work? If you do a trade with your prime broker, typically a large dealer, and it has a positive market value then you have created money that can be used in several different ways – even though not a single dollar has flowed anywhere, it is all modeled as future expected cash flows. The more “friendly” the statistical breakouts, the larger that discounted present value, especially if your broker can’t argue against your numbers; as Wall Street was unable to up until 1997.

In modeling future cash flows a whole world of math and variables opens up that allow for just such complexity; you have to predict not only various legs in swaps transactions, there are also counter-legs, the discount rate, and the biggest of the bigs, volatility. Nothing destroys any designed calculations like an unexpected rise in volatility. Therefore, there is enormous importance placed on being able to model, meaning try to predict, expected volatility, too. And that means hedging.

But introducing hedging for the math anyway creates a whole other set of calculations that are required, so that tolerances can be defined in the most complex set of interactions and counteractions. Those would include not just the expected performance of hedges, but also your expected flexibility in being able to further hedge should the original hedges perform unexpectedly. In other words, models that showed what would happen if you expect to lose control, and thus being able to quantify how you can control a position going way out of control – if so that the only purpose is for the math to define how all possibilities can be reduced to a single monetary calculation that shows you making money.

What is left on the other side of that equation is supposed to be random chance, but that’s really not what is there. Enron wasn’t felled by mere bad luck, they were cut down because of GIGO – garbage in, garbage out. There are any number of prominent examples, most of which were revealed during and after 2007. For example, like MF Global you can be right and have it end up very wrong:

In Morgan Stanley’s trade, the short position was likely paired with a long hedge position in super seniors of greater size (the estimates were for $10 billion). Where negative convexity plays a role is in its impact across tranches. While prices of the less-senior tranches were declining due to default fears and cash flow deterioration, the price of the super senior would exhibit very low volatility – until implied correlations hit that magical point where the correlation smile produces larger price volatility. That makes this trade seem like a perfect expression of a bearish outlook; make money on the middle tranche losing value while the super senior adds a hedge protection.

The problem was in their modeling of not only implied correlation and negative convexity, but the degree of reliance on derivative measures of financial parameters. As illiquidity was impacting credit spreads and Gaussian copula-based models were interpreting such moves as rising correlation, the negative convexity feedback loop was a blind spot since Morgan Stanley likely never modeled “irrational” fear driving illiquidity as an input. As implied correlation levels rose, the super senior began to take on the characteristics of a “long” trade in subprime, a truly bad place to be in the latter half of 2007.

The dazzle was in the process especially with Enron, the complexity so that you wouldn’t notice that none of it was sound from the very beginning. The same was true for LTCM, MF Global or Morgan Stanley as above, only their models were better in the respect they drew from more real world information rather than pure fantasy. It was for all “money” nonetheless, and it was all used as money for further purposes at least until the inherent contradictions became too glaring to ignore.

In other words, if your trades all assume that some currency irregularity in Thailand in 1996 is nothing to worry about but then all of a sudden it is, or that you are short subprime in 2007 at seemingly the exact right moment until out of nowhere you are not just long but billions long, the discounted present value of all those expected cash flows get flushed in the blink of an eye on a sudden burst in non-random random chance volatility (“tail risk”). At that point, those ephemeral expected future cash flows just up and disappear as fast and as easy as they appeared in the first place, only this time you have market values on your trades moving in the wrong direction and your broker demanding not better modeled numbers of future values but tangible collateral in hand right now.

This kind of math-as-money can be destroyed as quickly as it is created, but with more ferocity and ruthlessness in the reverse.

VICE CHAIRMAN MCDONOUGH. The biblical justice in this situation is that the principals of LTCM apparently believed so firmly that this system would continue to work that they appear to have borrowed rather heavily to increase their own risk positions in their firm. So, there is a general and spreading belief that we may have some extraordinarily elegant people in private bankruptcy court in the fairly near future.

MS. RIVLIN. How many more LTCMs are there?

VICE CHAIRMAN MCDONOUGH. We do not know of any other hedge fund that would be remotely of the size of LTCM/P. If John Meriwether can do it, there certainly would have to be other smart individuals with computers who could engage in the same sort of activity. So, there have to be little versions of LTCM/P.

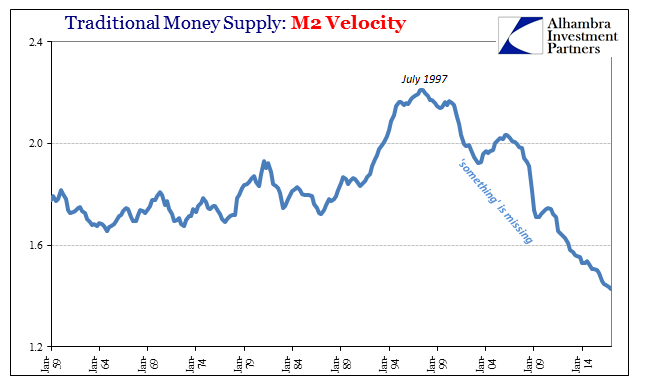

I have run across all kinds of famous last words, but these are some of the most frustrating; “there have to be little versions of LTCM.” Little? No. All of Wall Street became LTCM as money itself had already been transformed into discounted future values, credits that could be used to do monetary things and accomplish financial goals all in the present based on math about the future. In that situation, what is more money? It isn’t the actual exchange of actual cash, it is the various things that change the numbers about cash that in all probability will never move one side to the other under any circumstance. Whatever effects the calculations of those expected future cash flows is today more money than bank reserves or at the margins of the economy the stuff contained within M2 or even the incomplete M3.

Where it all becomes truly unmoored from reality is when everyone is doing the same thing, when there aren’t just “little versions of LTCM” out there but instead nothing but LTCM’s. You have math that shows a positive discounted present value of a complex series of transactions that gives you a credit on the balance sheet of a big bank dealer who obtains balance sheet capacity by doing the same kind of thing with some other counterparty who does the same with another and so on and so on. The monetary world becomes an impenetrable series of traded liabilities anchored to reality only by regressions, expectations for future cash flows that can accomplish what fifty years ago only a deposit account could.

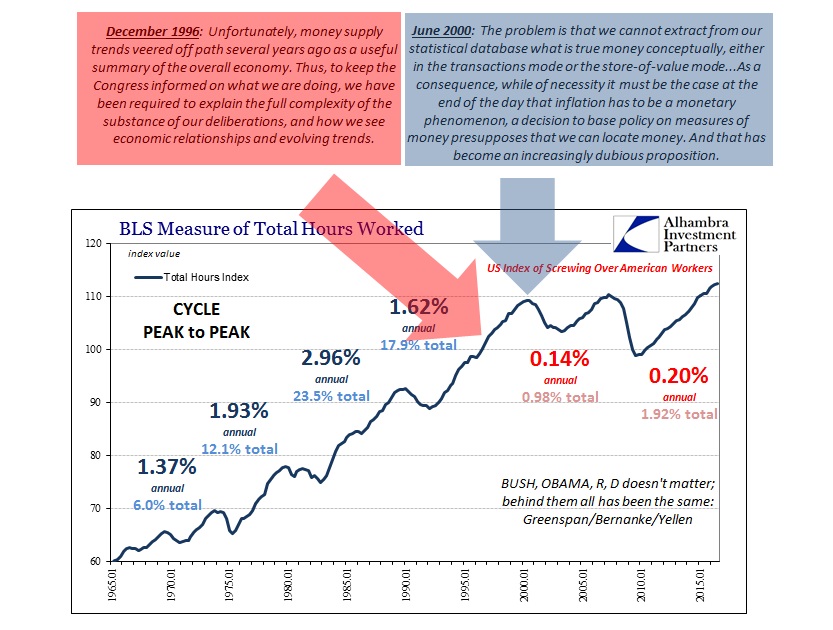

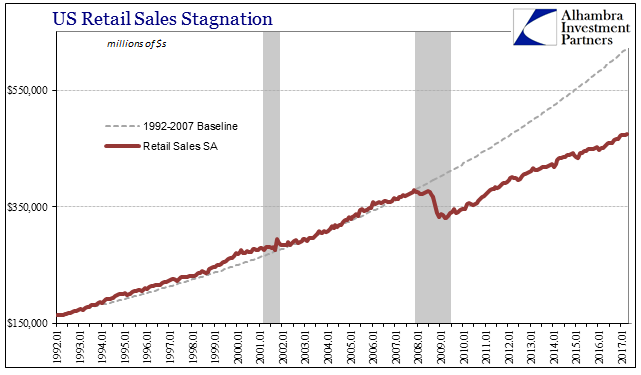

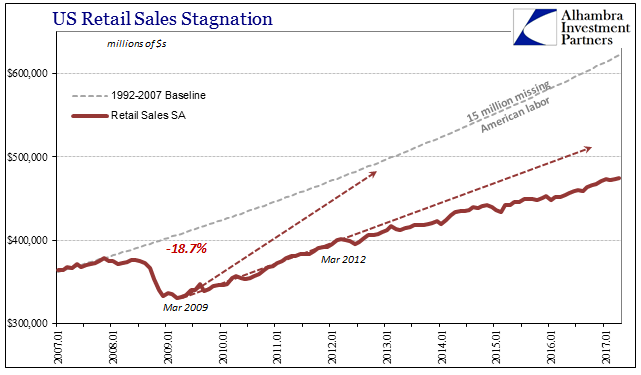

“Something” changed in the middle 1990’s, a genie set free from an evolutionary bottle that was downplayed and understated contemporarily even when the dangers occasionally forced themselves upon present time. There is nothing wrong with trying to forecast the future, nor even in trying to figure out what the future may be worth today. But turning that intangible expectation into something valuable, on terms equivalent with money, is a leap too far. The costs are nearly ten years of global depression, an enormous sum already but with no end yet in sight.

Thailand devalued the baht in July 1997, LTCM failed in September 1998, and somewhere in between Wall Street and more so Lombard Street figured they wanted in on all of it. It would not be just Enron that would have all the fun for however long it might last.

If this were just some stock and bond speculation gone awry, it would be an entertaining tale from afar, but by taking over money as if it were the math, and in many ways really is, the tragedy is our shared experience that continues even now. If the road to hell is paved with good intentions, the road to economic tyranny is littered with the efforts of some of the smartest people in history; those elegant intellectuals thinking themselves more worthy to re-arrange society, to all other exclusion, in a more “optimal” structure and finding themselves, and us, instead at bankruptcy court.

Why did QE and ZIRP fail? Other than briefly tamping down some projections of volatility in the first, maybe the second instance of it, after 2011 they were a complete nothing because they never really addressed the future where all marginal “money” still today resides.

Stay In Touch