Former IMF chief economist Ken Rogoff warned today on CNBC that he was concerned about China. Specifically, he worried that country might “export a recession” to the rest of Asia if not the rest of the world. I’m not sure if he has been paying attention or not, but the Chinese economy since 2012 has been doing just that to varying degrees often just shy of that level.

If there’s a country in the world which is really going to affect everyone else and which is vulnerable, it’s got to be China today. If there’s a country in the world which is really going to affect everyone else and which is vulnerable, it’s got to be China today.

The problem is, for Rogoff, a lot of debt which could at some point act as a further anchor as China attempts to restructure its economy from industry to the Chinese consumer and services. Such rebalancing is inherently risky, especially with so much debt supporting it.

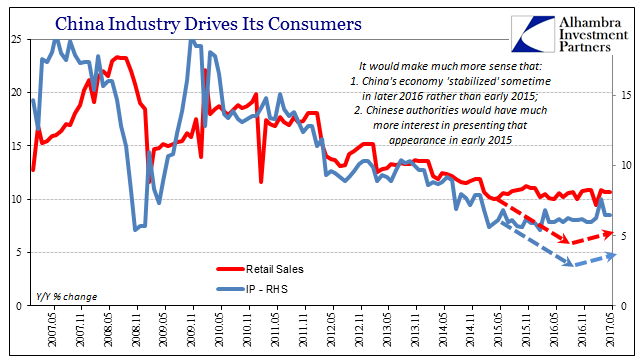

Again, I’m not sure Mr. Rogoff has been watching China all that closely. The government may claim that the economy is rebalancing, but so far there is little evidence at all it is actually doing so. Retail sales growth is today a third of the pace that used to be normal when China’s factories serviced the rest of the developed world. Industry is still at the heart of its economy, and most debt has been underwritten not for the coming Chinese consumer economy but instead in anticipation of going back to the rapid growth of its industrial past.

If there is any risk in China, it is that such debt is forced to be re-evaluated before the possible transformation is near enough complete (not getting much of a start would qualify). So long as Chinese investors and “hot money” holders believe it is legitimately plausible, then they might hold off on reassessing debt. China’s treasury market, however, this year indicates such processes might already be underway.

The big question is how long the system can maintain itself in such a stubborn state; where the consumer side fails to grow as anticipated for rebalancing. The less likely China’s economy is to hit that mark, the more likely debt begins to be reprocessed and ultimately repudiated at current prices. That’s not risk of China recession, it’s a transformational issue in the other (wrong) direction (permanent slowdown).

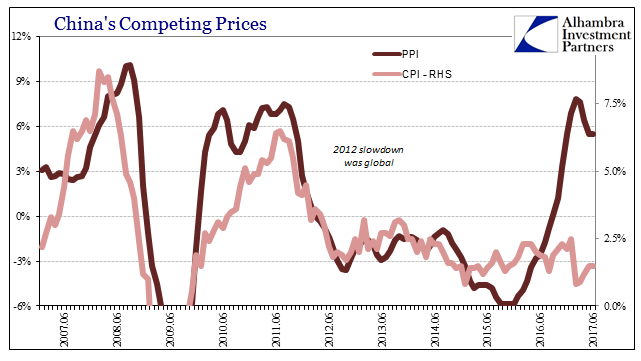

The latest economic data from China continues to suggest this lack of progress. Both the Producer Price Index as well as the Consumer Price Index in June matched the estimates from April and no more. In terms of the CPI, it, like the inflation measures in the rest of the world, persists in rejecting economic improvement; suggesting instead that the whole idea of better fortunes this year was a creation of a dumbfounded media still expecting a happy ending to everything.

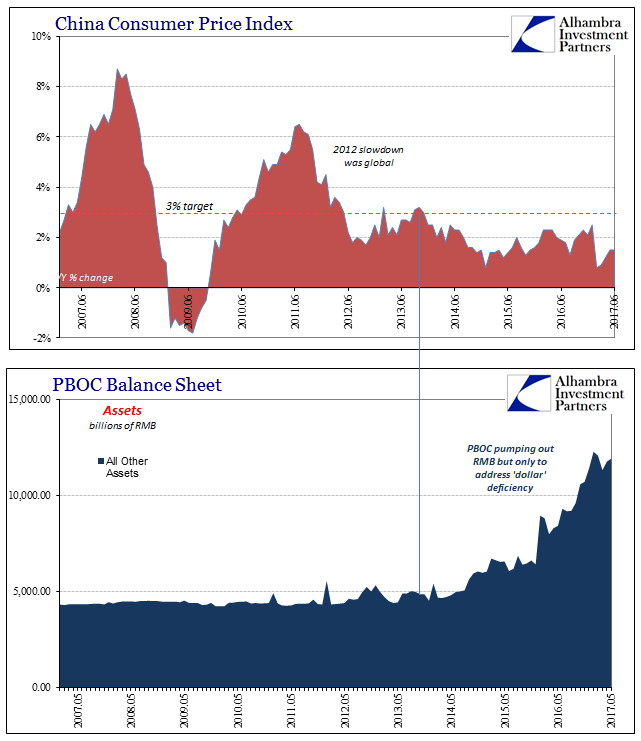

Like the Fed, ECB, and BoJ, the People’s Bank of China has been over the past few years forced into heavy action. Since December 2015, when growth and monetary risks were at their worst, the PBOC has expanded the RMB portion of its balance sheet by more than RMB 5.5 trillion (thru May 2017). That’s an enormous monetary program by any definition.

The lack of acceleration in consumer prices points to the lack of monetary momentum in China’s economy despite it. Unlike those other central banks, the PBOC balance sheet includes the reason for the absence of positive results – forex, meaning “dollars.” China’s economy can’t gain any traction because monetarily conditions have only been tight no matter what the central bank does. That’s what China’s treasury market is now signaling, joining the rest of the world in trading for the exact wrong scenario. These are the growing indications of China’s interest rate fallacy springing to the forefront.

I feel it necessary to close by repeating that this isn’t supposed to be how 2017 was predicted to unfold. The end of the global downturn in 2016 was thought to lead into measurable, inarguable improvement; a plausible path to something different. Instead, there is everywhere only more of the same. So much, in fact, that even orthodox, mainstream economists have chimed in, if several years behind.

Stay In Touch