The world of eurodollars is always going to be hidden. What goes on, really goes on, often sees no light of day. The most basic financing transactions are typically bilateral, meaning that the only people who really know the terms and the reasons are the two counterparties engaged. That is also true if one of those counterparties just happens to be a central bank.

Central bankers have in the 21st century quite proudly proclaimed their commitment to transparency. This is very different from how monetary policy had developed through history. It used to be convention that markets didn’t want to know if or when or how a central bank stepped in, and central bankers didn’t want markets to know that either. Call it mutual self-delusion, but custom called for monetary policy in actual money to be swift and quiet.

The modern model for monetary policy almost has to be the opposite, if for no other reason than there is no money in it. It is almost entirely an expectations management exercise, therefore by that nature it must be loud and obvious (too loud and obvious since 2007, of course, conclusively proving only that there is no money in monetary policy and thoroughly undermining expectations). Officials like Ben Bernanke hoped that by being more transparent it would lead to better appreciation for what the Fed was doing and more robust expectations as a result (rather than the opposite).

Some central banks, however, aren’t fully in that mode of operation. These still prefer to operate with some degree of opacity if not complete blindness from time to time. Perhaps unsurprisingly, these are often the central banks where money still is included in their monetary policy.

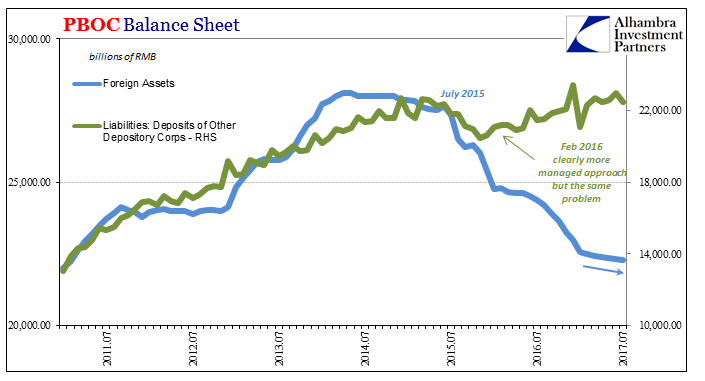

I am primarily referring to the PBOC. The Chinese monetary system is mostly of the traditional depository format (where bank reserves count as money), with only very recently the wholesale model inching onshore. Where those systems collide is really in the forex area, putting Chinese traditional money in the hands of wholesale eurodollars.

What actually happens at that crossroads, however, we may never know. We can from time to time detect the often clumsy and heavy presence of someone doing something, and therefore infer China’s central bank participation, but most often it is by connecting the dots of outlier type events or price trends.

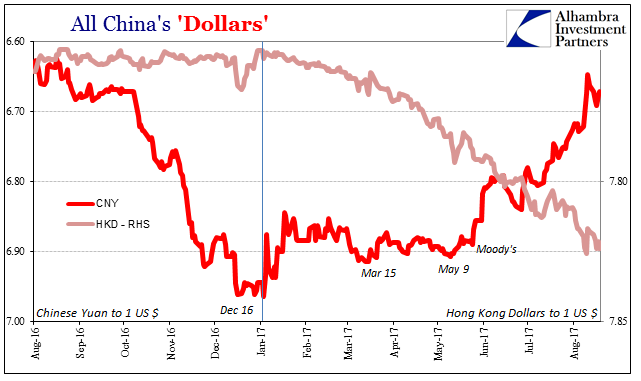

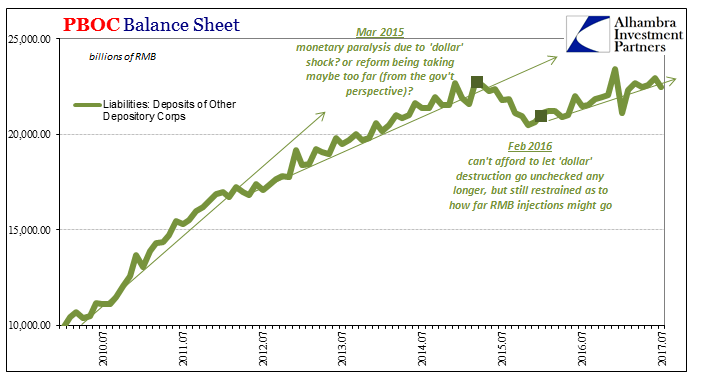

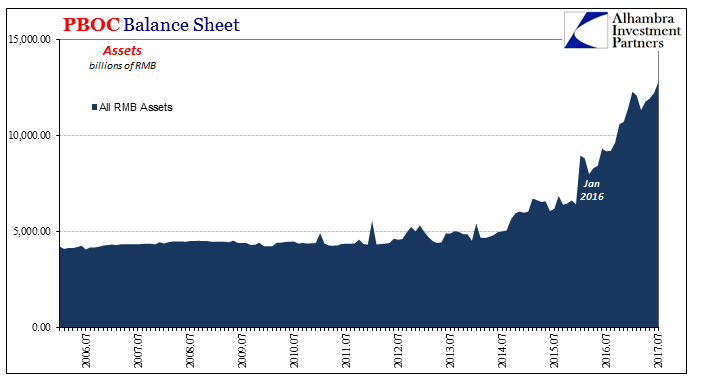

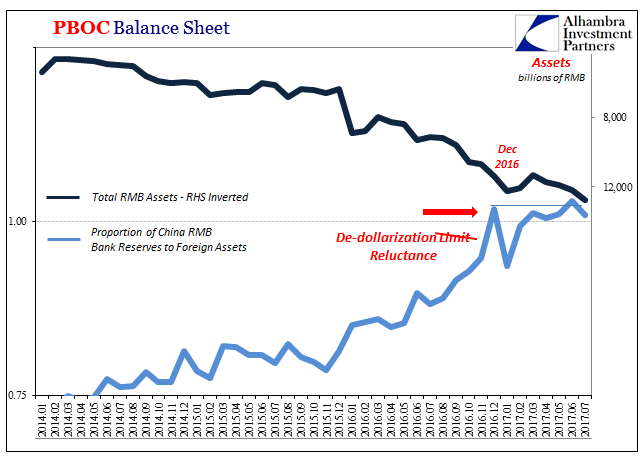

That used to be CNY “devaluation” and its keeping a perfectly regular schedule (ticking clock). It seems very clear that Chinese monetary authorities realized sometime in late 2016 how destructive that was (because it wasn’t actually devaluation). What drove CNY down was not interest rates, differentials, or even threats real or imagined over money printing (RMB). In fact, the more RMB that has been injected over the last year or so the less unstable the currency.

The issue is risk and nothing more. So long as China’s economy and financial system are perceived to be at risk, the currency could only react in further destabilizing fashion. The cycle easily becomes, as it did, self-reinforcing; unstable currency leads to effective monetary tightening reducing economic growth, heightening risk perceptions leading to more unstable currency and so on.

To break the currency cycle, the PBOC has tried any number of things including for a five-month stretch in 2015 pegging CNY to the dollar again just as it had done in the “dollar” troubles of 2008-09. That didn’t work and very likely made it all worse (like compressing a spring), as we saw in August 2015. What is perhaps relevant to today is that the PBOC has shown itself perfectly comfortable with experimentation. Resisting transparency can appear to be a benefit from certain points of view.

CNY has in the past three months actually appreciated and by quite a bit, which is what the PBOC and the rest of the government has been seeking all along. That could very well be due to “looser” financial conditions, as the FOMC has confusedly referred to them, related to less global “dollar” pressure this year compared to last year; the end of the “rising dollar” as it were (to be clear, my use of the “rising dollar” only refers to the period that began in June 2014, with roots stretching back to the summer of 2013, and not the whole eurodollar decay decade; it is or maybe was but one phase or event within that overall systemic condition that is clearly ongoing, if at an ebb or pause the past year).

But the CNY appreciation truly got going after the PBOC changed the calculation in the daily exchange trading band for dollars. That was almost surely in response to the Moody’s downgrade of Chinese sovereign debt, a potentially damaging result that could have heightened risk perceptions all over again.

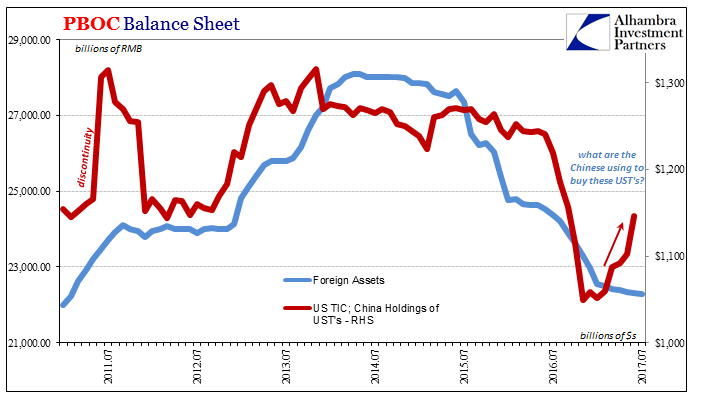

Just a few weeks later, Chinese officials made a public point to announce that they were buying US Treasuries again. Having been forced to sell off an enormous quantity during the “rising dollar” period, they seemed particularly eager to highlight their expectation for such degradation to be, in their judgment, past tense. According to TIC figures the Chinese have been doing so all year but stepped it up in June, so the announcement and more so the timing of it seems peculiar in the same manner of managing risk perceptions.

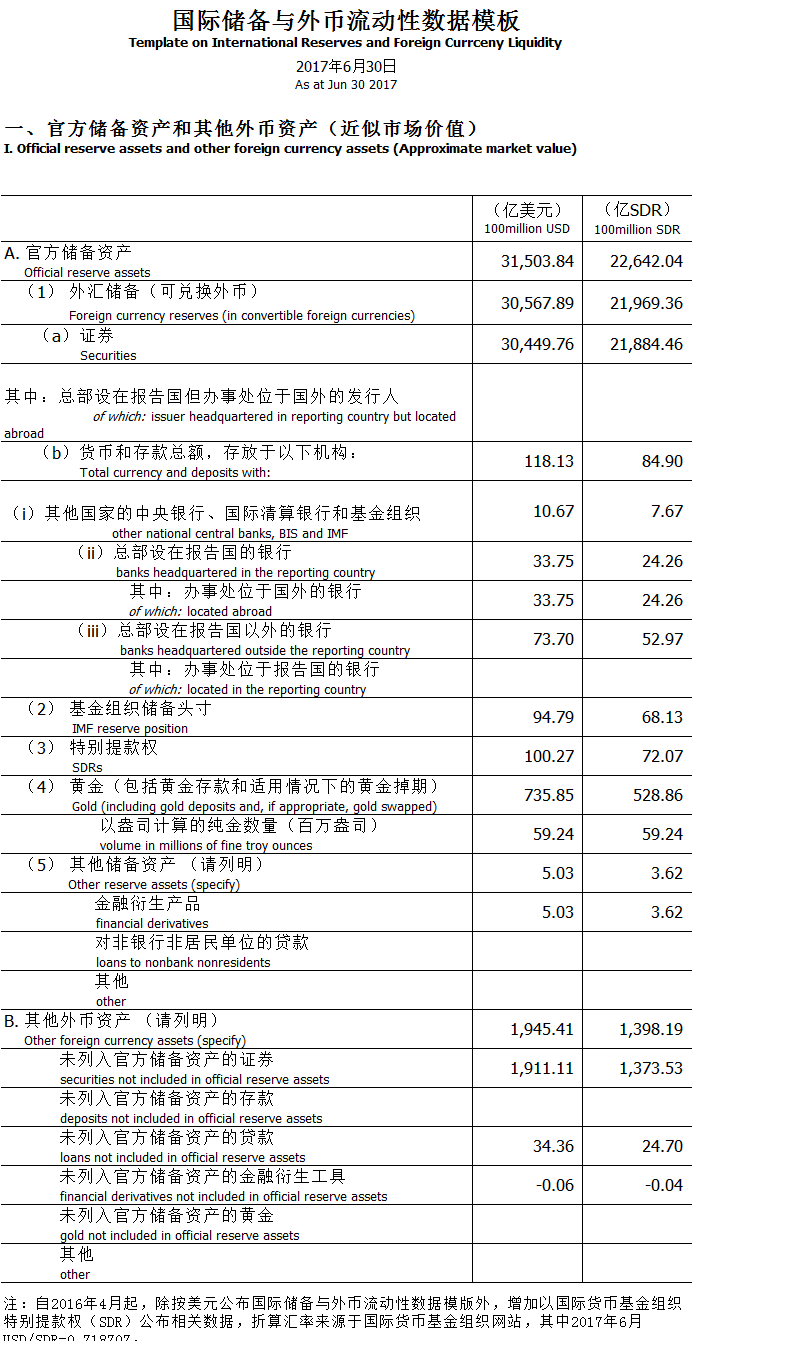

That sets up an interesting divergence, perhaps one of these outlier dots waiting to be connected to something else. The central bank itself reports its forex assets continuing to decline, the very basis of the Chinese monetary system. If they are buying UST’s, especially since June, what else has to be going on?

To clarify, we should not expect a perfect relationship between TIC data and the PBOC reporting of its asset holdings. The latter is far more comprehensive in that there are much more than UST’s in those tens of trillions (RMB) of assets, and the PBOC is not the only official agency active in these places (including holding UST’s). But what else is in there? We don’t really know.

It could be that the PBOC is selling euro-denominated assets to raise dollars in order to buy UST’s, to make it seem like China has no more “dollar” problem. Or perhaps Hong Kong dollars?

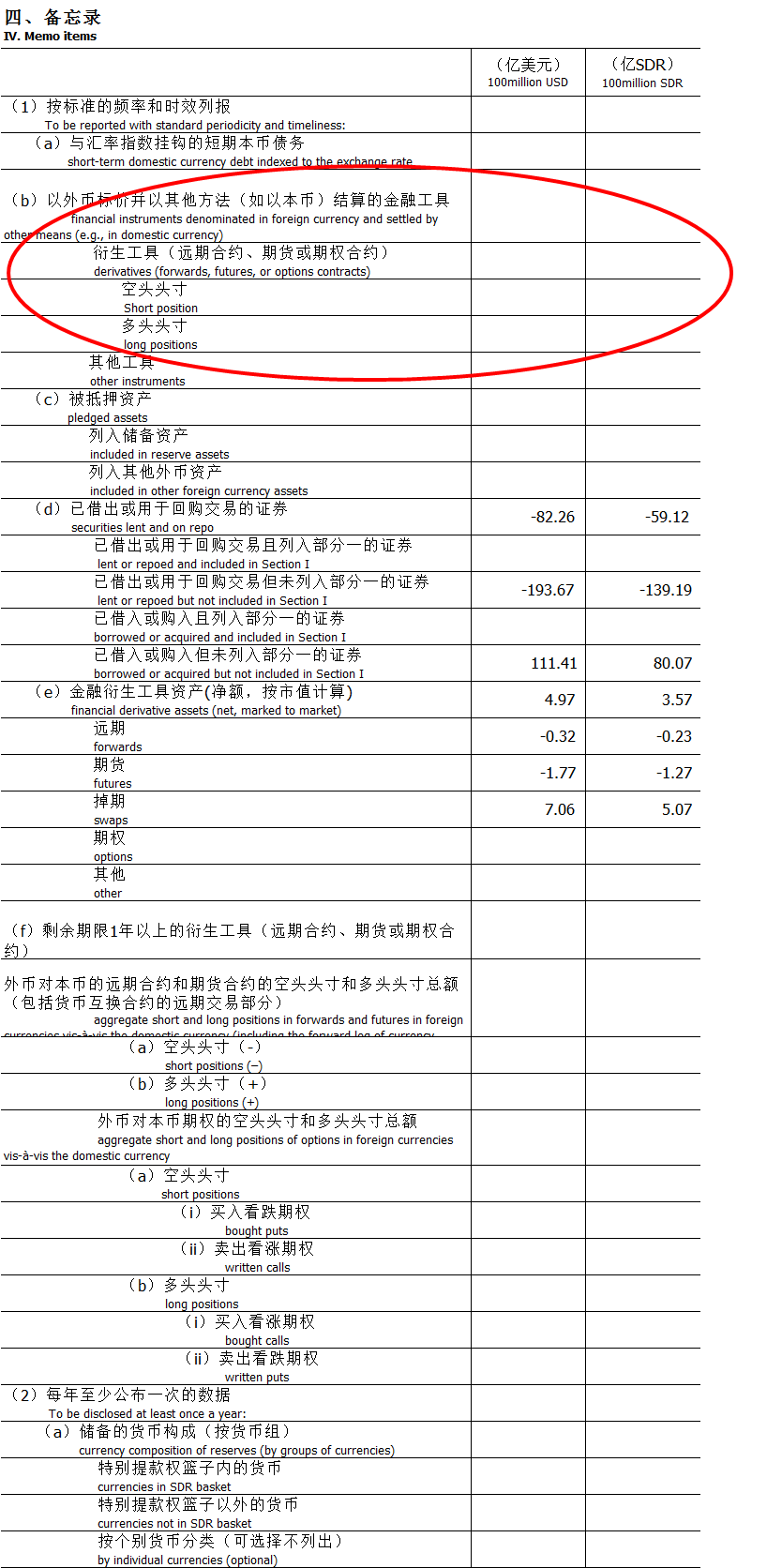

If they are using HKD as an intermediary, the PBOC could do so without leaving any trace as far as accounting. The IMF templates for reporting such things remain empty in the places where swaps, forwards, and term funding arrangements would show up. Not only that, the PBOC can direct its banks to undertake these or similar transactions on its behalf.

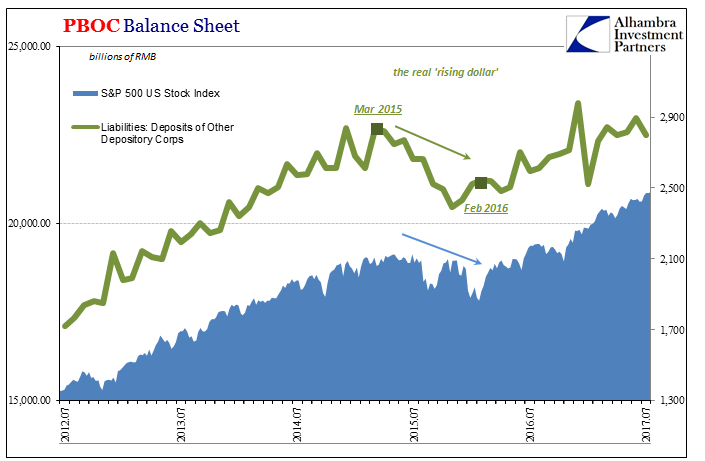

The simple fact is that Chinese monetary policy, which includes CNY and therefore “dollars”, matters a great deal to the global economy and its markets; both as a reflection of global monetary conditions in “dollars” as well as affecting perceptions of more than liquidity risks. The ability and willingness of the PBOC to manage its RMB policy under the “rising dollar”, whether ended or still ongoing in some other form or phase, has had an enormous impact on the global system.

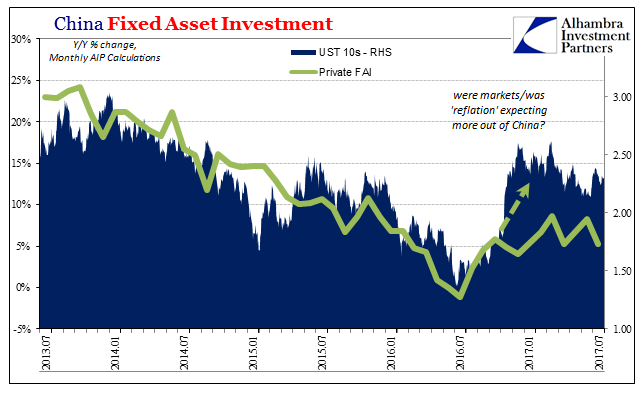

The effect of Chinese monetary policy, as a consequence of global “dollars”, was more than just those two stock liquidations shown above. There was the much greater matter of a serious global downturn that resulted in a near-recession here in the US and by all accounts so far in 2017 one with no real rebound or recovery. The whole economy worldwide has become that much weaker for it, and Chinese monetary policy at that time played a big role in that outcome.

The question to ask now is, “are they finally getting it right?” To my analysis, sadly, it doesn’t look that way. No matter what they do the PBOC might be doomed because the real problem is bigger than it or China or any single country. The best that might be said is they had a big hand in ending the “rising dollar” phase, but that’s still far short of ending the eurodollar decade.

I wrote last summer that global monetary policy is “written in Chinese after being developed in Tokyo and Hong Kong (and maybe still London).” It doesn’t appear as if that has changed, though the manner in which it is carried out or why may have.

Stay In Touch