Orthodox monetary theory tells us that central banks matter, a lot. Monetary policy is supposed to be the difference in everything from economy to currency. If one central is doing one thing and another central bank something different, it is presumed the only necessary information to infer what markets and therefore economies might do in response. The Federal Reserve is “tightening” while the Bank of Japan remains on QQE (with YCC and clowncar rack and pinion steering). Therefore the US dollar is rising against the yen, right?

That’s obviously a loaded question where we know the answer to be the opposite. It’s not the only case where these sorts of orthodox assumptions have been clearly violated and in important ways for vitally important reasons.

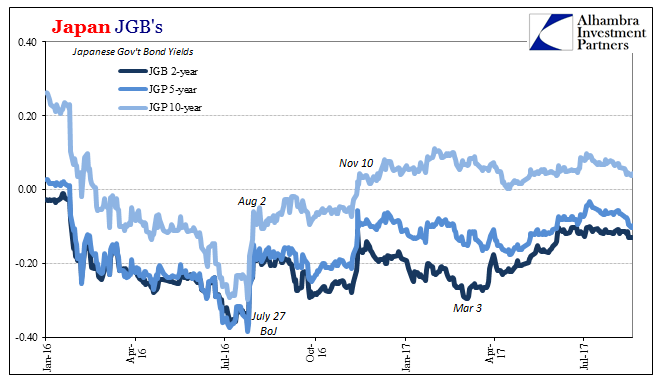

Japanese government bond (JGB) yields have been rising at the short end. They aren’t really yields of course, but negative interest rates for Japanese banking institutions overpaying the privilege of holding liquid alternates to NIRP-attested reserves. The rise in the JGB 2s, for example, is like that of the German 2s where starting around March there was some less enthusiasm for paying each government as an “investment.”

Yet, that improvement so far as liquidity preferences has gone has not translated into higher nominal yields down the JGB curve. That’s surely the BoJ, right? After all, YCC, or yield curve control, was aimed at the 10s to make sure that yields there stayed predictable – and they have, for the most part.

The point of the exercise, however, was to steepen the JGB curve so as to signal if artificially to the global bond market that things really were improving in Japan in tandem with economic improvement elsewhere; the ubiquitous yet intangible and never definable rising “global growth.” In other words, it was expected that negative 2s and shorter would remain or even lessen further like European markets, thus keeping the 10s near and around 0.00% would mean a steeper curve.

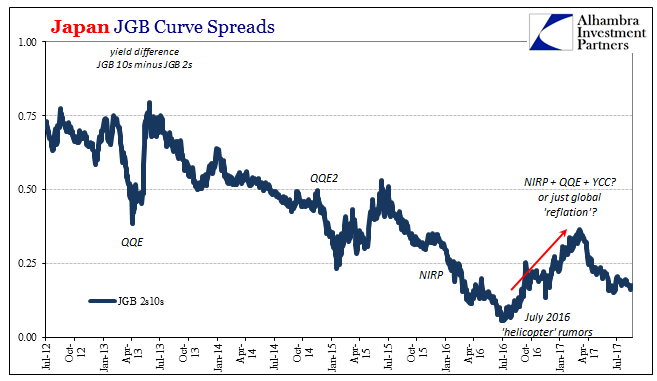

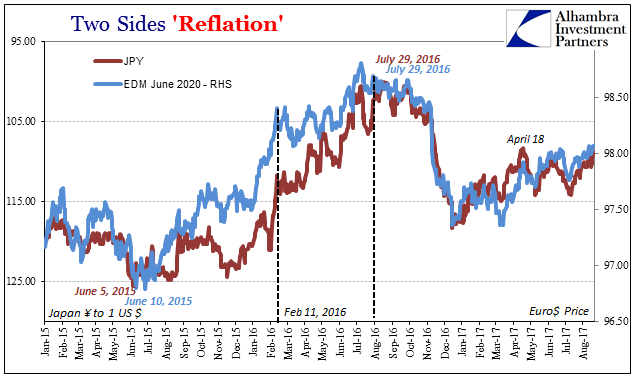

It worked, or appeared to, for a little while. Again, going back to early March the opposite case has returned. In fact, the chart you see above should be uncannily familiar but in a way that isn’t supposed to happen:

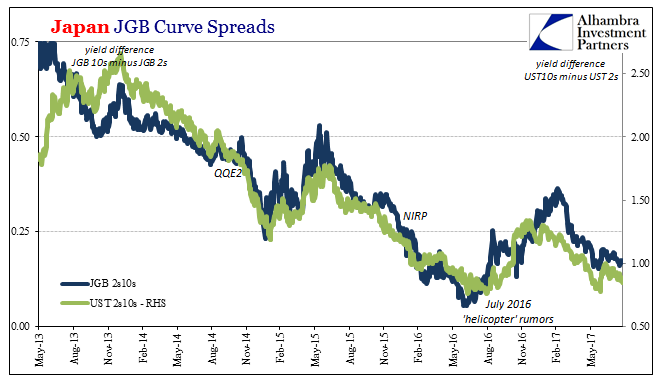

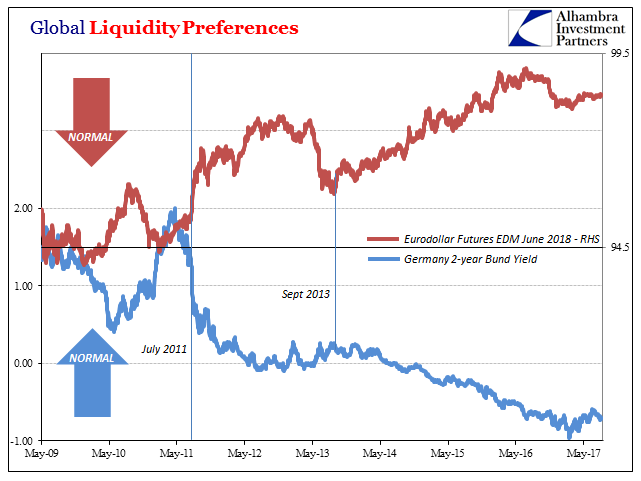

Going back to the last “reflation” in 2013, the vital middle of the US and Japanese yield curves have behaved as if linked by “something” else other than central banks doing all sorts of different and same things if also at different and the same times. It quite appears that monetary policies, indeed central banks, might not actually be all that important in setting market views, for not even the Pacific Ocean stands in the way here.

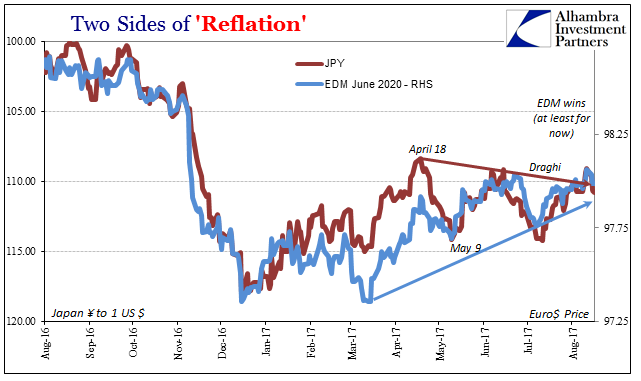

Though the degree to which each is being moved is different, the similarity of pattern and raw timing is undeniable; as it is in other ways and market prices (including the yen, which has found its appreciation again despite American RHINOs).

There is “something” else going on here, as I wrote earlier this week (subscription required):

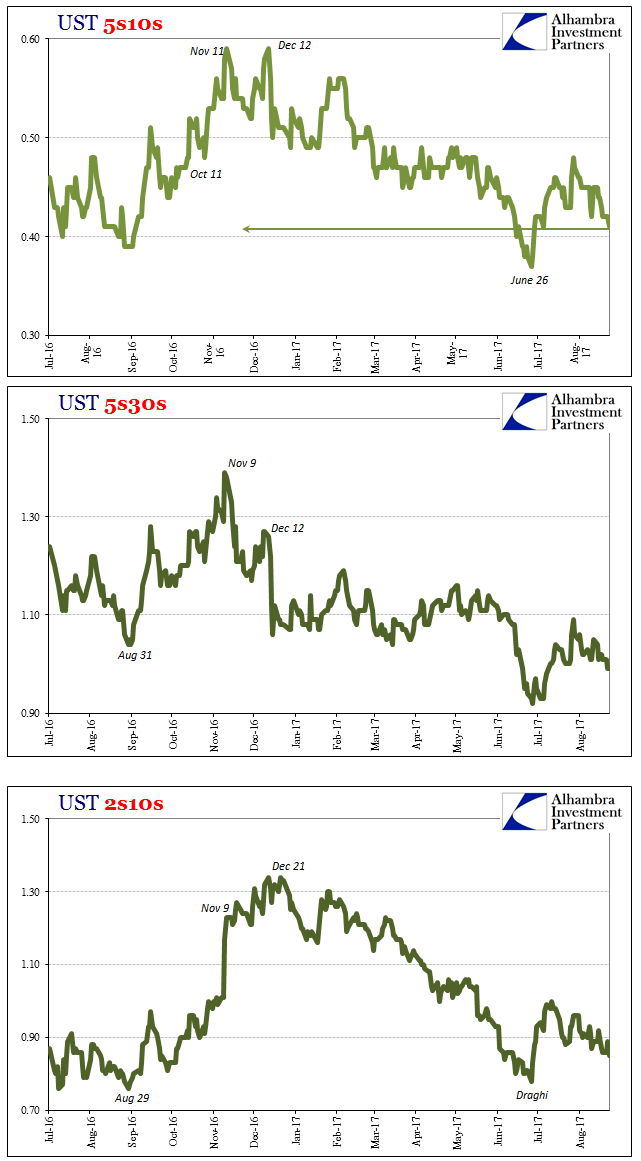

If we think back to the middle of last year, the world was in an ugly place. There was deep pessimism to be found almost anywhere you looked, outside of the stock market, of course. Bond markets had grown so dour as to force central bankers, heretofore unshakable enthusiasts of all things QE, to re-assess and re-evaluate it from the ground up.

Curves, in particular, had become so flat so as to be unrecognizable as curves. From eurodollars to UST’s, low straight lines became the order of the day. What they meant was equally as troubling as the absence of any welcome upward rounding slope. The outlook for money opportunity, meaning global economy, in these conditions was for prolonged stagnation and malaise in addition to the almost ten years which had already been suffered.

The nominal frame of reference, which is all that central banks really do, they can’t change the more important spreads that really matter, has shifted only slightly. The rest of these markets are more and more like last summer when the impossible pessimism was its most impossible. It wasn’t anything more than ill-conceived and almost certainly temporary (for the third time) “reflation” sentiment that briefly interrupted the longer trend. Nothing ever goes in a straight line, not even global monetary breakdown.

As noted earlier, there is growing statistical evidence as well as a wider body of real world anecdotes that things are not improving beyond some insignificant degree (the return of positive numbers doesn’t mean what everyone seems to believe). Markets would seem to concur in a lot of different places and in a lot of “impossible” ways.

Stay In Touch