The fundamental problem is that we don’t know what’s wrong. In many ways that is a worse condition because it is one step further removed from a solution. Even after ten years “we” still have to prove that the one thing everyone largely believes can’t be the depressing issue is.

Earlier this year as the price of oil began to slide all over again, the media was flooded by analysis of what would otherwise appear to be a grave contradiction. The trade in crude like many commodities is a signal of monetary conditions as much as fundamental imbalances. In fact, the two go hand in hand especially for oil, because the intersection of economy and finance is located practically in Cushing, OK.

In late June, Societe Generale’s Albert Edwards wrote:

After the [global financial crisis], central bankers have collectively spent the past decade stepping up the pace of money printing to new extremes in an attempt to drown the global economy in liquidity.

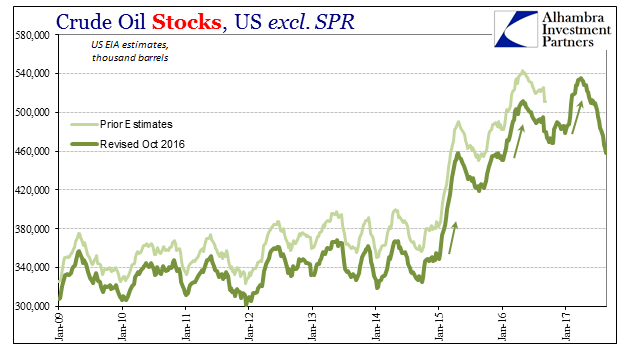

So why isn’t WTI $150 if not $200 a barrel? It’s the same mistake as was made in late 2014 and especially early 2015. Because for these people there is no monetary issue to speak of, the oil crash had to be due to a “supply glut”, and a “transitory” one at that.

It didn’t matter that slowing economic growth, which was obvious at the time, combined with commodity declines are textbook monetary deflation. The orthodoxy of QE overrode common sense and long-established principles. It was Economics over economics, and despite what has transpired since it still is.

Because of this misdiagnosis, there remains a great deal of confusion about the economy in 2017. In an orthodox, binary world of recession/not recession, the economy of this year no longer appears to be at risk for the former, so it is widely believed that in the category of “not recession” there can only be good things.

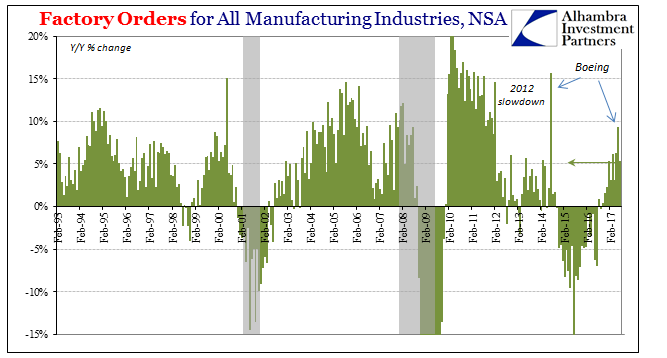

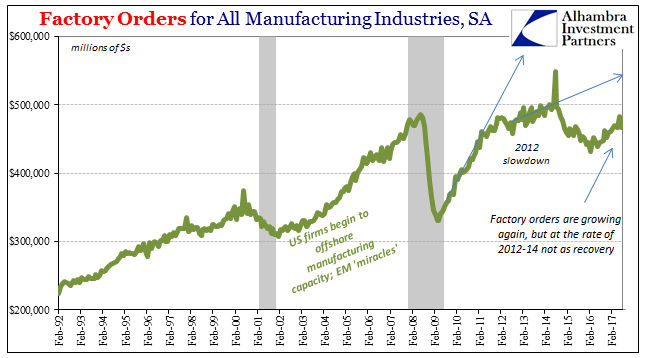

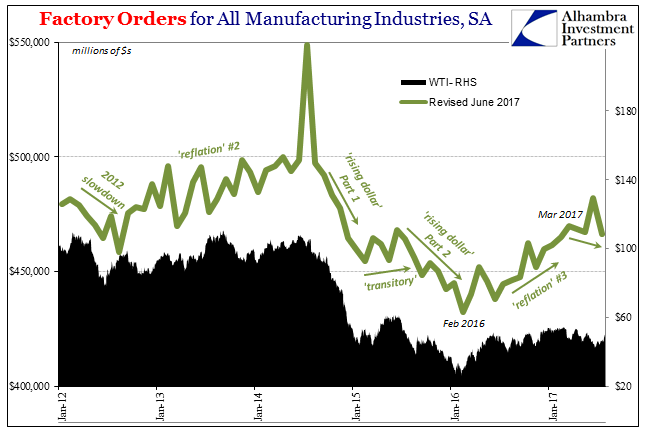

Factory orders were reported today as rising just 5.4% year-over-year (not seasonally-adjusted) in July 2017. After contracting for 22 months straight starting in October 2014 (the obvious slowing), 5% is nothing, barely any difference in strength or momentum. Even the prior month’s (June 2017) Boeing anomaly couldn’t push order growth into double digits (+9.3%) where it should be as a minimum for the scale (more so the duration parameter) of that contraction.

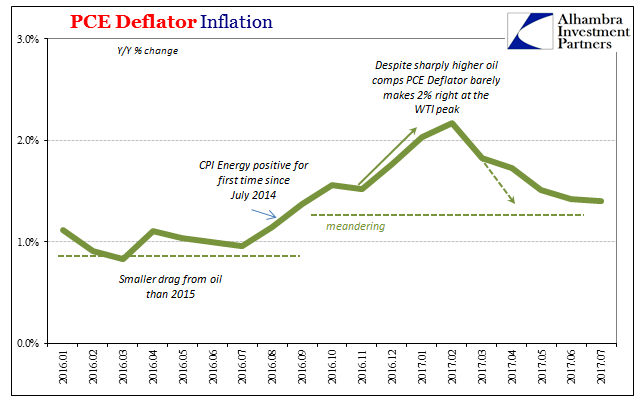

What that tells us on an economic level is that demand, however it may be, remains as reluctant today as three or five years ago. There was no “supply glut” for oil, and therefore there was no “money printing” or flood of liquidity, at least not in the real economy. More important, however, is that there is none now. The monetary drag rolls forward.

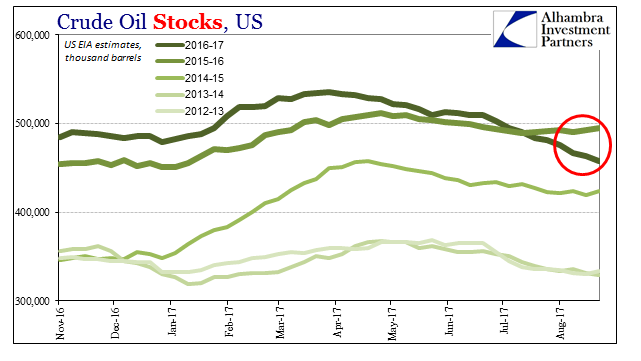

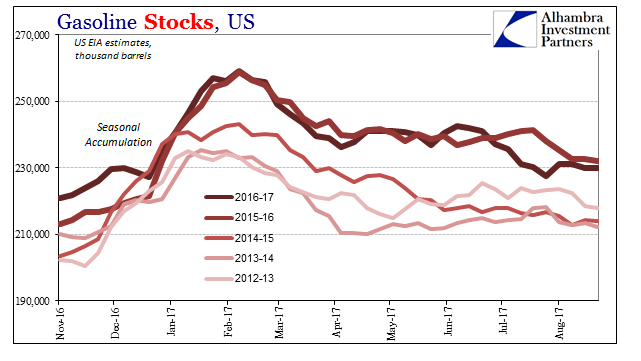

Oil inventories have declined, substantially, but that has been nothing more than the same economic characteristic as anything else. It’s not meaningful improvement (especially gasoline) so much as a lack of further contraction or erosion. There is still more oil in storage in Cushing today than there was at the worst of the downturn in early 2016 (and way more gasoline).

Oil production has come back, of course, but it is really demand that continues to be the missing ingredient in oil prices, therefore inflation, therefore economy.

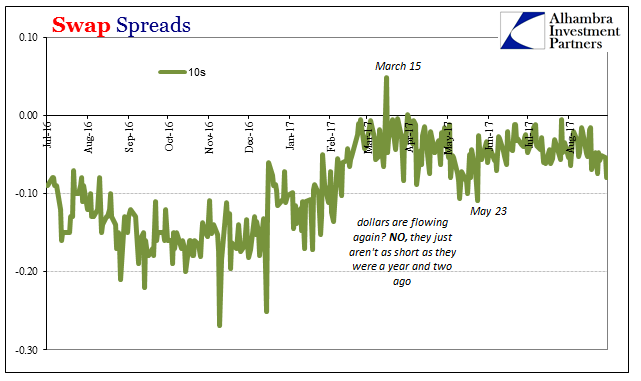

What should be concerning in the summer of 2017 is now more than just the lack of momentum. Several of the same monetary indications (bond rates, eurodollar futures, swap spreads, etc.) that warned about “deflation” trouble before are doing so again. Translating that into the proxy for economic demand in factory orders, this data suggests (seasonally-adjusted series) that apart from the Boeing anomaly in June factory activity may be once again waning.

That could be just monthly statistical variation to be revised by more complete surveys and data in the future, but factory orders are lower in July than in March. Like the coincident turn lower in oil prices, that length of time argues for significance.

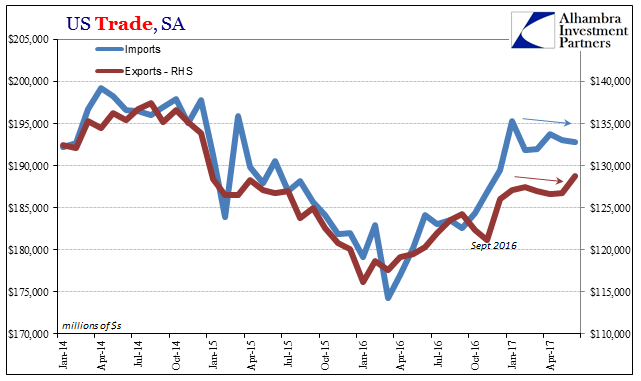

And it’s not just factory orders, as any number of economic accounts have stalled out in practically the same way at practically the same time.

That strongly suggests not just the economic barometer that oil prices have become over the past few years, but more than that what is and has been behind oil prices since 2014. Textbook deflationary pressure is sometimes textbook deflationary pressure.

The difference in late 2016 wasn’t that it dissipated and left us for truly “not recession” conditions, but that it abated to some minor degree enough for “not recession” to seem a plausible outcome. Data over especially the past three or four months in conjunction with market prices (especially those related to money) are starting to rollover again increasingly erasing that scenario.

In the parlance of central bankers, it leaves us with a heavier downside risk bias.

Stay In Touch