The Communist Chinese established their independence on September 21, 1949. The grand ceremony commemorating the political change was held in Tiananmen Square on October 1 that year. The following day, October 2, the Resolution on the National Day of the People’s Republic of China was passed making October 1to be China’s National holiday.

It typically kicks off the second of China’s Golden Week holidays. The first relates to the Chinese New Year festivals, taking place in either January or February. Both weeklong holiday celebrations can present a challenge for monetary authorities due to the length of each one.

With banks closed, the Chinese people tend to carry more currency than they might otherwise. The banking system therefore has to adjust its liquidity profile, holding internally more in front of the Golden Weeks and leaving somewhat less in interbank markets. The PBOC will intervene as it sees fit to address any outsized shortfall.

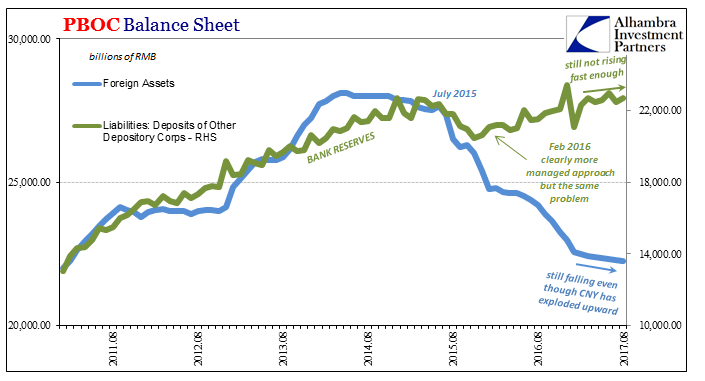

That was the case earlier this year. The Chinese banking system was handed a sudden and unofficial 100 bps reduction (large banks) in the RRR back in January, theoretically unlocking more of China’s bank reserves due to reasons that were never explained or acknowledged. It wasn’t hard to figure out why, however, as interbank rates in China were doing all the wrong things.

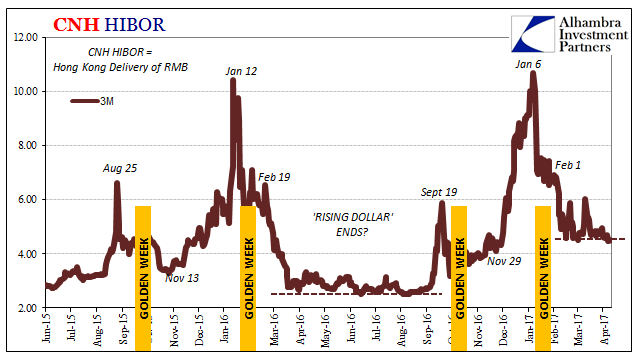

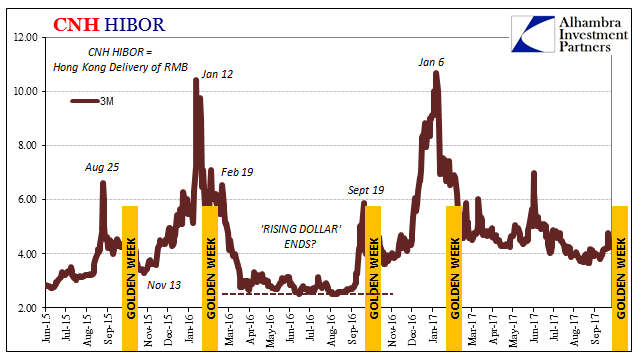

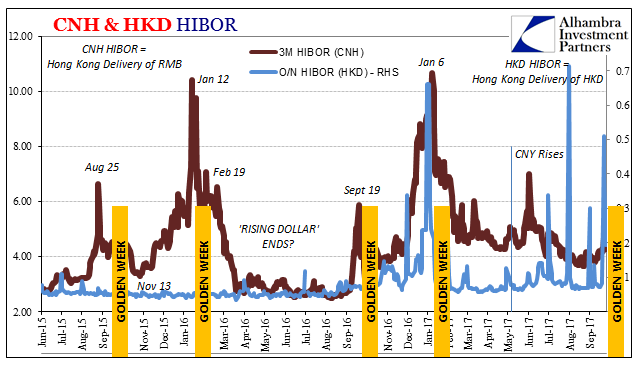

That included offshore money rates (CNH). Not only does the Chinese money market feature these calendar-related liquidity ebbs or bottlenecks, there is also Hong Kong to consider along the same lines of obstruction. Hong Kong may be a Chinese city, but it still features a distinct currency regime.

In a bid to modernize the Chinese monetary system, authorities established this offshore trading of RMB (CNH). What makes a modern reserve currency unofficially is not who accepts it but where they do. The Europeans established the euro as a political tool, but in monetary terms its role was to challenge the eurodollar not dollar. CNH was meant to be China’s offshore answer to both.

Recent times have been far more challenging toward that goal. As with most things China, CNH is desperately misunderstood. Somehow the mainstream Western media (deference to all things Communist) has the idea that this market is only for speculators to borrow RMB in order to short CNY through CNH. Every time money rates surge in CNH, the stories appear blaming speculators betting on “devaluation.”

Because the offshore RMB trading takes place largely in Hong Kong, the money rate associated with this CNH is called HIBOR. But there is another HIBOR, too. It deals with the local currency market in Hong Kong, the Hong Kong dollar (HKD). The two are not meant to be related.

What we find over the past two years since the huge global monetary imposition of the “rising dollar” are these seasonal bottlenecks further amplified by the structural offshore one. Banks cut back on free interbank liquidity due to the Golden Weeks, leaving more RMB interbank borrowers stranded and isolated in Hong Kong. What’s unusual is the degree to which this has happened, as China’s banks are constrained by “dollars” and thus further in RMB.

It has only happened in the past few years, connecting China’s overriding monetary issues with those of these local or RMB terms. In the context of 2017 and the PBOC’s shift to a stable (or rising) CNY policy, it is in their interest to gain a handle on offshore RMB.

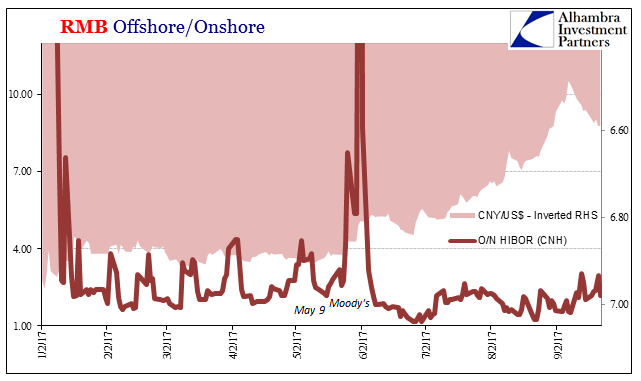

With October 1 approaching once more, it appears that CNH money rates have broken the pattern. There has been no appreciable disturbance in offshore RMB not just so far in September but going back to late May. Problem solved?

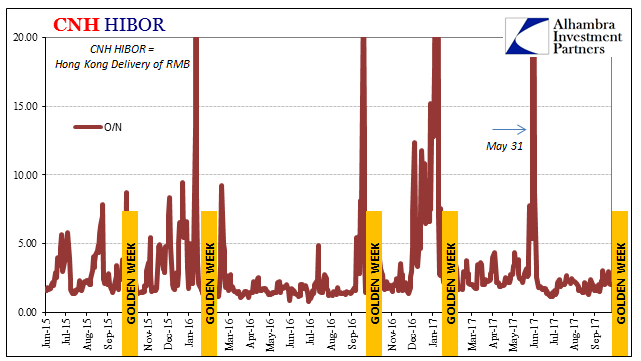

Not so fast. There is to start a break in the pattern in another huge surge in offshore HIBOR (CNH) in May. On May 25, the overnight rate jumped from 2.773% to 4.165%. A week later, to end the month, the HIBOR interest rate was 21.079%.

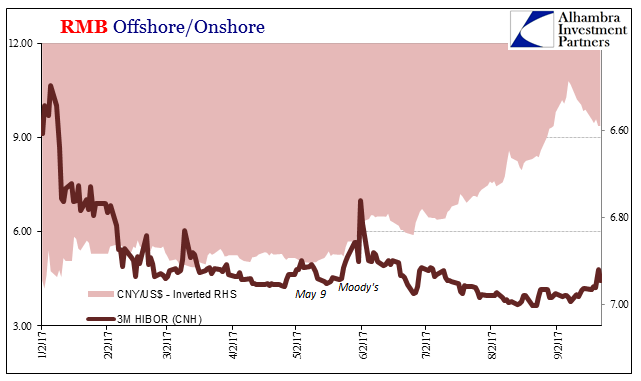

If that timeframe sounds familiar, it should. On May 24, Moody’s downgraded China’s debt. It’s not that investors were digesting that event in CNH trading, rather it was almost surely in response to how Chinese authorities responded to it.

The PBOC, of the things we know, changed the way the currency band was calculated. Couched in bureaucratic technocracy, the intent of the shift was perfectly clear. Standing on a stable CNY policy, monetary officials were not going to let Moody’s ignite another CNY drop.

It didn’t, and outwardly given the calm seasonal approach of the next Golden Week it does seem as if the PBOC might be congratulated for a job well done. The problem, however, is that every central bank policy is but a tradeoff. The purpose is the belief and expectation that the benefits of any tradeoff far outweigh the costs. In this case, the benefit has been months of rising CNY and calm CNH.

What are the costs?

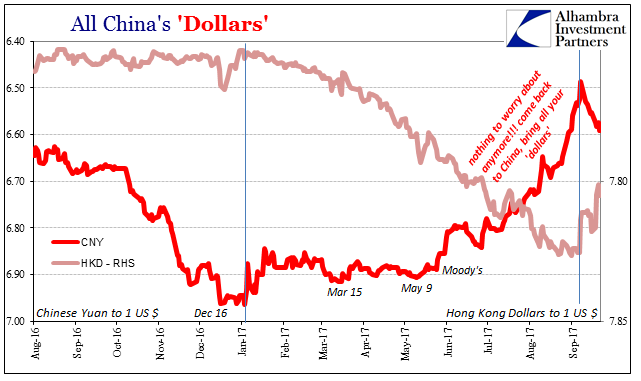

From the very start even before Moody’s and May, China’s major currency problem (eurodollars) seems to have been transformed rather than cured. The tradeoff has almost certainly been to shift its center of gravity into Hong Kong instead of mainland China. That’s not to say that mainland China has been largely free of the “dollar’s” continued disruption, it hasn’t been.

What we are seeing in Hong Kong, I believe, is the other side of the CNY policy. This location transformation, for lack of a better description, began almost certainly last year. It did not at first take the form of currency exchange values, either HKD or CNH, but more so HIBOR for Hong Kong dollars. In other words, the seasonal Golden Week bottleneck visited HKD for the first time in October 2016, and then increasingly into the next one (January 2017).

If Hong Kong CNH rates are stable in September 2017, Hong Kong HKD rates are not. The scales are not comparable, so the spike in HKD HIBOR (O/N) to 0.51018% last Thursday is equivalent in CNH HIBOR to something like 8% or 10% on the benchmark 3-month rate.

Exactly what is going here continues to be a hidden mystery, and most likely a tangled, convoluted one. In general terms, however, I think it relatively simple and as described above. Chinese authorities in a bid to disguise any further negative CNY tendencies have shifted them through unknown means onto Hong Kong – first offshore CNH (late 2015), then both CNH and HKD (late 2016), and now HKD more exclusively.

To make such things more remote requires more effort, therefore greater costs when the bill for the policy tradeoff comes due. That was at its heart the “ticking clock” for CNY; the costs of trying to intervene being added to the failure of that intervention.

We don’t know what this Hong Kong stuff could mean this time around, other than considering the ways reflexivity might play a role (where the effects of a cause cause effects on the cause). To this point we will have to be content with the only truly reasonable inference where all of this can be distilled down to its lowest common denominator – “dollars.”

Hong Kong doesn’t have a “dollar” problem, China does. If Hong Kong has developed one, it isn’t very likely to be anything other a transformation done so with added energy and emphasis. Those additions as well as their mere existence tell us what we have suspected all along. The difference between 2016 and 2017 was never an end to the eurodollar issue. The specific part or phase related to the “rising dollar” may have concluded (not surprisingly during a Golden Week), but the structural eurodollar issues dating back ten years linger ever onward.

The way in which various places attempt to deal with the never-ending problem has evolved; the results have not.

Stay In Touch