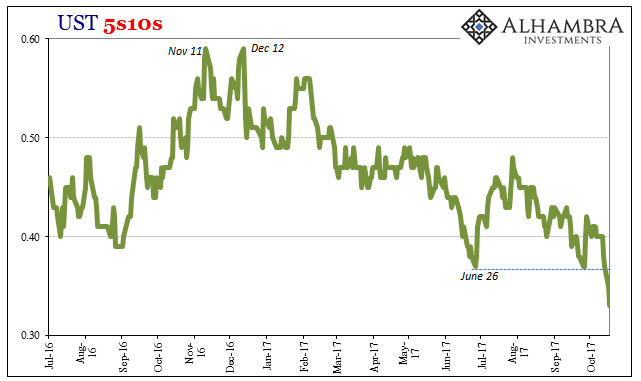

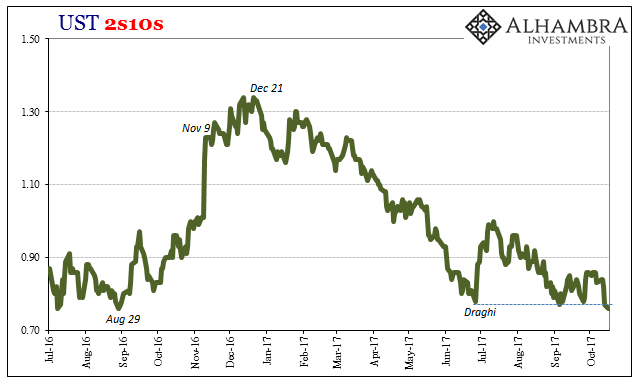

At this point in the longer term process of unwinding the Fed’s prior emergency activities, the yield curve was supposed to flatten. That was the plan all along. If monetary policy was successful, or had even run into just dumb luck somewhere in the last ten years, here where policymakers declare the economy to be short rates would be moving faster than those at the long end.

The flattening is taking place, to be sure, and more so over recent weeks. But it isn’t the same process as would have defined success and recovery; it is instead the opposite indication.

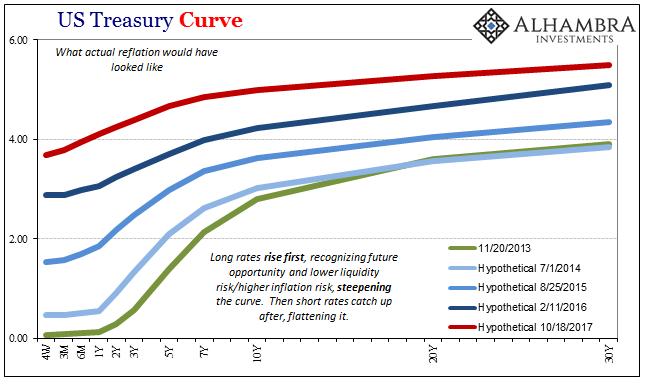

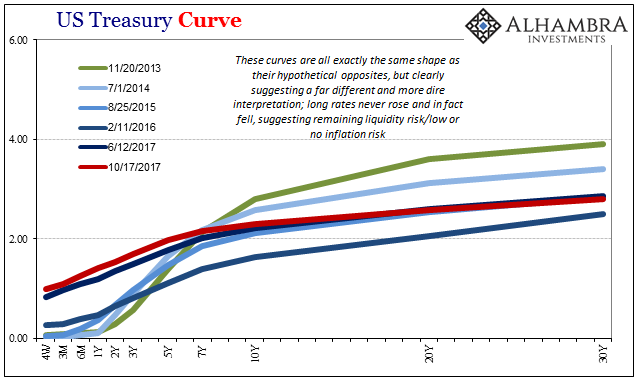

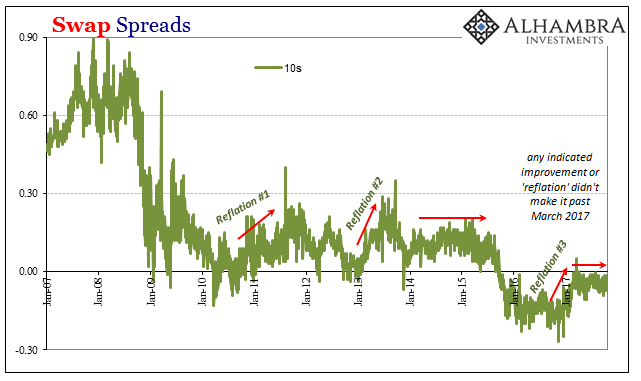

Actual recovery would have been predicted by long rates. Sensing a real reduction in liquidity risk in combination with higher inflation risk (both of which equal out to higher economic opportunity), long rates would have risen faster first, well ahead of short rates stuck at or near zero. The resulting steepening would have been a very positive sign; as it was taken to be in Reflation #1 and Reflation #2 (Reflation #3 was appreciably less so).

But those prior “reflations” were incomplete, or at the very least interrupted. They never got nearly far enough, as the market recognized instead that the basis for them was really lacking (and to some degree more emotion than rational analysis; this last one was surely almost all the former, which is why it remained so small and therefore rational by comparison). As a result, the yield curve twice re-compressed (flattened) prematurely (from the policy perspective) as long rates came back down.

In this third “reflation”, long rates have been more steady while short rates are now moving (in historical comparison still very slowly). The result is the same for the curve, and it’s the opposite of what recovery would look like. The treasury curve is compressing again and to new low levels because it is telling the world that nothing has changed other than the Fed’s attempt to redraw the short-term frame of reference.

What’s going on at the long end is more than just fuzzily negative economic assessments. Finance is all about risk, in UST’s perhaps more than any other market. Macro risk is certainly part of that, but it doesn’t have to be so non-specific.

Again, bonds are really very simple, which is why economists have so much difficulty with them. Liquidity risk and inflation risk are much easier to classify and visualize once you step past the central bank myth. QE didn’t do a single thing about liquidity no matter how many times the media repeats the lie that it was “money printing.” Recognizing that monetary policy has had little to no effect especially on footnote dollars and the like, liquidity risk appears very different than how it is described (inflation risk being almost the perfect flipside of liquidity risk).

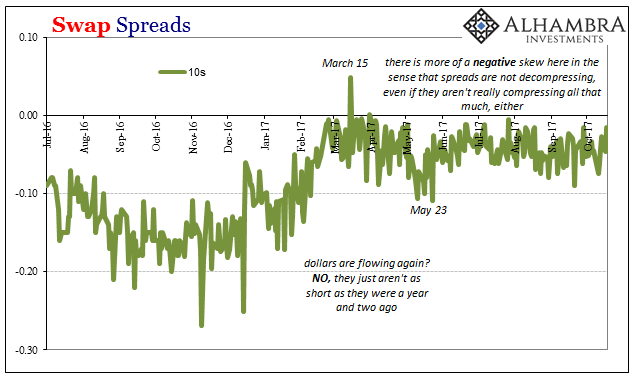

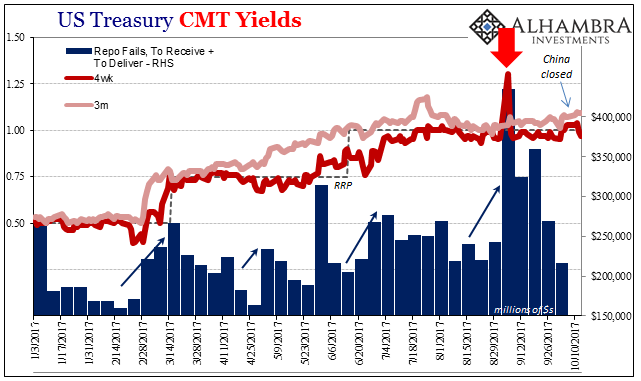

We have observed already several key shifts in these deeper liquidity spaces this year, several important ones clustered around March. There was another, as noted several times, in early September. Both of those involved the repo market in at least being the most visible outlines of significant difficulties.

So it is of little surprise to find that cross currency basis swap premiums turned very negative again in mid-September following the repo market disruption. The euro swap (for more on basis swaps and what they mean, go here) that had rebounded to -22 bps “premium”, suddenly lurched downward to around -40 bps where it has been since. The yen swap reached -30 bps on the upside, but is now back around -50 bps.

To the mainstream, this is all again confusing:

There are several forces at work that are raising the expense of financing in dollars. Strategists cite the political tension in Spain related to Catalonia’s independence push and the slow pace of Brexit talks, which may be heightening the perception of credit risk for the region’s banks. Combine that with the prospect that a U.S. tax overhaul could trigger dollar repatriation, and the outlook for monetary-policy divergence with the Federal Reserve starting to unwind its balance sheet, and analysts see the trend only worsening.

“This is keeping a lot of people feeling uneasy,” said Gennadiy Goldberg, an interest-rate strategist at TD Securities in New York. “This now seems more of a political story, with Catalonia, U.K. Brexit negotiations and potential U.S. tax reform and repatriation. Spreads could keep widening.”

It’s not anymore a “political story” than it ever was, apart from politics increasingly being dragged into the mix by just this kind of denial. And so it is accompanied by the usual benign banalities that have been offered time and time again with each reflation’s “unexpected” end. It is much easier for most people to believe that some political disruption in Spain or the Trump administration changing something causes an increase in uncertainty than it is to realize the monetary system is broken and the world’s central banks (apart from the Chinese) have no idea that it is, where it is, or even what it is.

I’ve written several times before that the “next one”, meaning the almost inevitable episodic monetary interruption waiting out there in the future, will not be unexpected at all; the “rising dollar” having been suggested as it was in 2014 by a series of escalating warnings (as the events in 2010 advised about what was coming in 2011).

What stands out this time is an almost perfect example of the butterfly effect upon a truly fragile system (the emphasis on fragile). The drama of September 5 and the 4-week bill was nothing, a little one-day detour in a single liquidity instrument. And yet, here we are six weeks later watching these serious ripples flow across the whole global “dollar” system. It’s the opposite of resilient, and it describes tremendous liquidity risk (if something so small can cause all of that, what might something else with a little more gravity do?).

The flattening of the yield curve in 2017 as merely continuing the trend since Reflation #2 broke down almost four years ago is the bond market telling the world of this imbalance of money and the very real risks it imposes. Rinse. Repeat.

Stay In Touch