We live in an age of statistics. They are everywhere, including a whole lot of junk numbers (endless studies) that don’t pass minimum scrutiny. Somehow, statistics have become the gold standard for at least the mainstream media in framing our view of everything from new discoveries to further exploration into how things work.

That’s fine for a discipline like quantum physics where the utterly complex probability models have been repeatedly tested and validated. It’s a far different proposition in the softer sciences where the rules of science aren’t as easily determined.

In 1972, Karl Popper in further defining the scientific process in this modernizing age said that,

Whenever a theory appears to you as the only possible one, take this as a sign that you have neither understood the theory nor the problem which it was intended to solve.

It’s a warning that I try to take to heart, seeing as I do eurodollars lurking ominously behind every global problem. But Popper also said at the same time, “no rational argument will have a rational effect on a man who does not want to adopt a rational attitude.” In other words, as long as I stick to a broad enough survey of evidence then proceeding as I do on the monetary explanation for at least economic deficiencies is a legitimate, rational inquiry.

For others in places of power and influence, this is just not the case. Claiming, as Federal Reserve officials have done, data dependence does not make it so. Words are cheap, and like it or not central banks all around the world have been in heavy action for ten years. That’s a record of experimentation more than sufficient to draw reasonable, sound conclusions.

If you knew nothing about what each of these monetary institutions had done this past decade, instead realizing only what the economy has been like at each significant moment along the way, you might expect that central bankers were busiest in 2008 before becoming much less so over time. That was, after all, the time of greatest obvious and immediate need, when the economy was crashing.

Given how the economy is described today in pretty glowing terms, it would seem as if there would have been far less of a requirement for monetary intervention the closer we have moved toward recovery. And that’s how things are being described, here and everywhere else. Policymakers themselves don’t much use that word, but the others that they do use (“transitory”) all point in that direction.

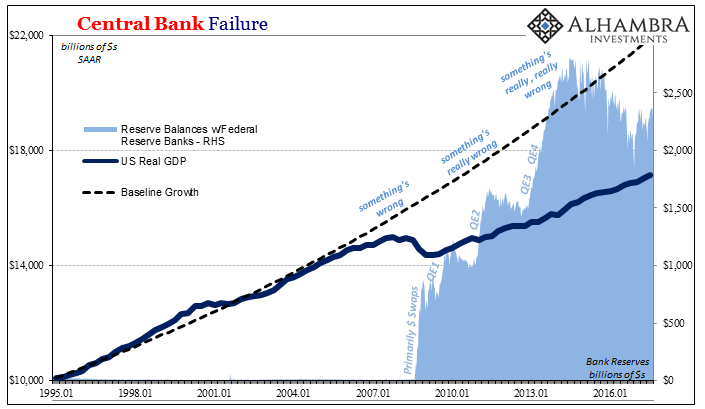

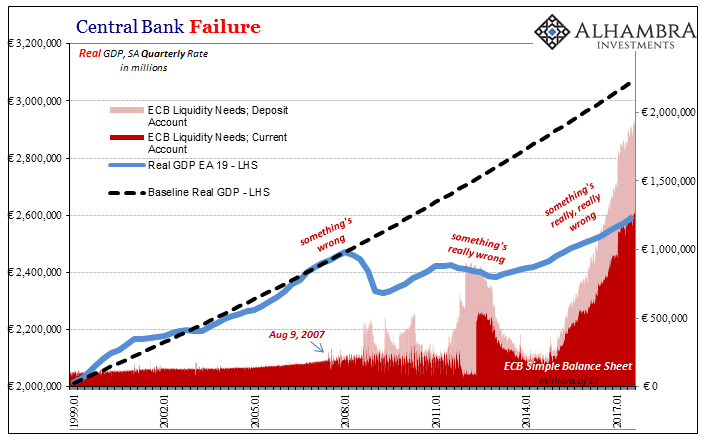

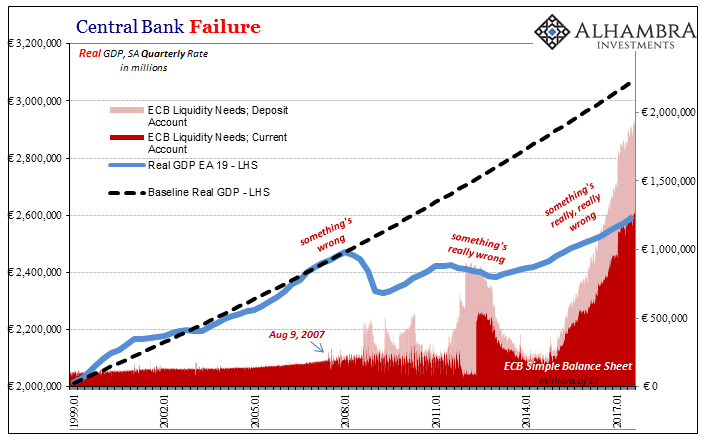

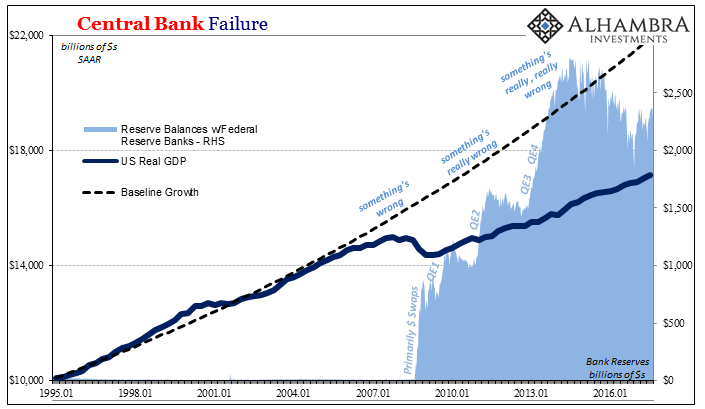

But that’s not what happened. Central banks actually started small and have only escalated from there. In three separate doses, each of the majors (I’m focusing on the US and Europe here, but you could also include China and Japan, the latter grouping together its plethora of QE’s into specific intervals) have significantly increased the size of their “stimulus” programs over time.

Given that the worst contraction took place, again, in 2008 and early 2009, it doesn’t seem obvious why the Fed and ECB would wait until many years later to really go big; that is until you realize that what’s motivating these central banks is not the immediate linear contraction in GDP but instead what’s holding each economy back from reaching actual, complete recovery.

To put it another way, what really has mattered in setting monetary policy is the gap between actual output and where these economies would be if the Great “Recession” had actually been a recession. The Fed, ECB, and the others, especially PBOC among that latter group, all responded based on that distance and really what it was that was creating it (for them exogenous, hidden eurodollar decay).

Because it happened in succession like that, their immediate impulse was to go bigger each time, an act almost of palpable frustration in reverse order to how you would think it would go. As each iteration was thwarted by “something” outside of their worldview, they met the challenge by changing the quantity variable in QE even though direct, linear economic consequences were smaller after 2008.

These gaps matter, even if central bankers and Economists (redundant) can’t directly appreciate them or why. They kept trying harder as more time passed because these programs weren’t working. Though the single contraction was larger ten years ago, it really represented just the initial departure point where the problem has only grown bigger.

By acting in this way, the smallest of silver linings has been their very experiments disproving the theories behind them – especially the one that views bank reserves as universally useful “money.” At least that is the scientific view of the grand scheme, for Economists are ideologues rather than scientists, rejecting as they have clear falsification.

According to the Wall Street Journal yesterday (and thanks to M. Simmons for the thankless task of keeping up with these dogmatists), some Fed officials know that there is something very wrong but that instead they just need to keep doing what hasn’t worked until it does. I’m absolutely positive that’s not what Karl Popper had in mind, for what is called here a “seismic shift” is nothing like one.

Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco President John Williams says fundamental uncertainties about the economy mean officials may need to weigh a seismic shift in how they conduct monetary policy.

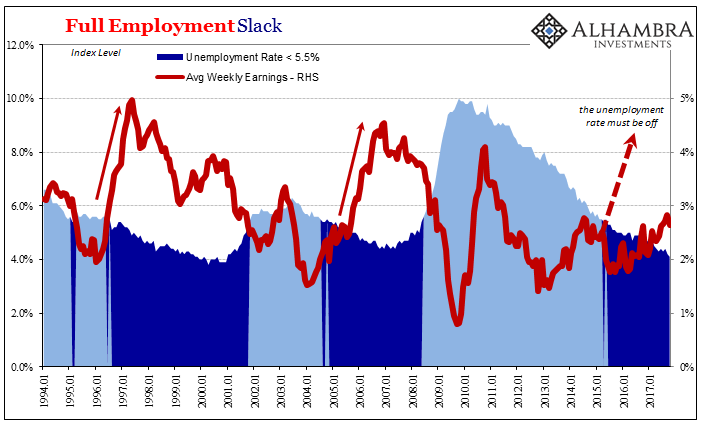

What fundamental uncertainties? Primarily, at the moment, these:

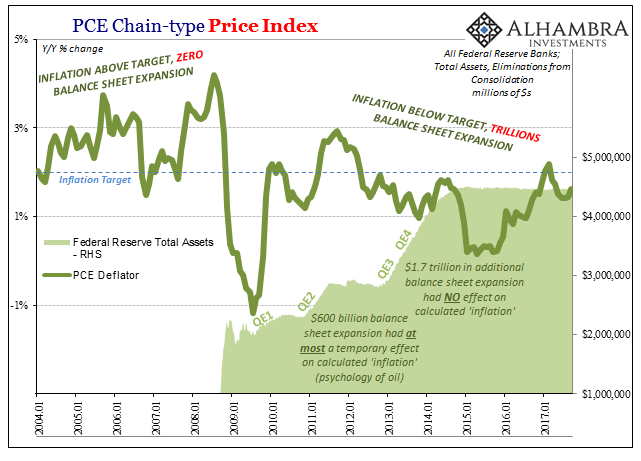

To address them, Williams wants to look at price level targeting, changing the monetary policy definition of price stability from an inflation-centered one (the change in price levels). As San Francisco Fed President, he has a significant platform for influence within the FOMC, having bolstered his orthodox credentials with a great deal of research into R* and other related matters that seem to have achieved an official following for his views. Thus, as an influential Fed official, we have to be grossly discouraged by this:

“If your price level is below target like it is today, because we’ve had years of running the inflation rate below our target and the price level is now well below what the target would have been if we had a price level target in 2012, it would say just keep stimulating the economy without really focusing on is this the right employment or output level,” Mr. Williams said.

“It would just say keep stimulating the economy until you get that price level back up,” said.

How about instead of “keep stimulating” we actually look at the evidence whether anything has been stimulated at all. Again:

That’s ultimately the issue with all of this. Policymakers like Williams refuse to question their most basic assumptions, the foundation of every central bank that simply assumes that if it creates bank reserves (or just reduces some short-term interest rate) it automatically equates to “stimulus.”

This apparently unshakable belief is grounded in nothing more than regressions made and calibrated during a world that doesn’t any longer exist (and let’s face it, the world never stands still, so even in any other time period it’s a dangerous, subjective assumption to believe that you can define mathematical rules for the future based on the present or the past). And these models endure because Economics is not science; it is a belief system that features so much complex math it just seems like it should be.

It’s why you see the backwards escalation of monetary programs across the world, the idea that monetary policy did stimulate just not (never) enough. Only now after ten years, the results are all negative on the first indication; no stimulus at all. Changing the target for what they do will have the same negative effect and costs (wasting time). The rational, scientific answer would be for central banks to instead begin investigating how to change what they do (stable global credit-based currency).

Stay In Touch