First Bernanke, now Yellen. As I wrote earlier today, there is a growing tendency to revise economic history at least as it applies to official actions. Ben Bernanke defends QE from the perspective of 2009 forward, as if 2008 was all just someone else’s problem irrelevant to the world that came after. In effectively resigning from the Fed Chair position as she did yesterday, Janet Yellen assumes judgement from the same Year Zero:

The economy has produced 17 million jobs, on net, over the past eight years and, by most metrics, is close to achieving the Federal Reserve’s statutory objectives of maximum employment and price stability.

That’s true. Between October 2009 and October 2017, a term of eight years, the BLS’s Establishment Survey figures a positive difference of 16.96 million payrolls. If, however, we judge the Fed’s performance from the prior peak, as is appropriate, the record is cut in half, only +8.58 million net gained. In terms of full-time employment, the “growth” is worse still, just +4.8 million despite 22.8 million added into the prospective labor pool (Civilian Non-Institutional Population) over that time.

“If you measure it only from the bottom we don’t look so bad” isn’t exactly a happy retirement sendoff. Yellen also uses another weasel word prominently in just that one sentence. After all this time and effort, the economy is still only “close” to where the Fed thinks it should be. How can this be?

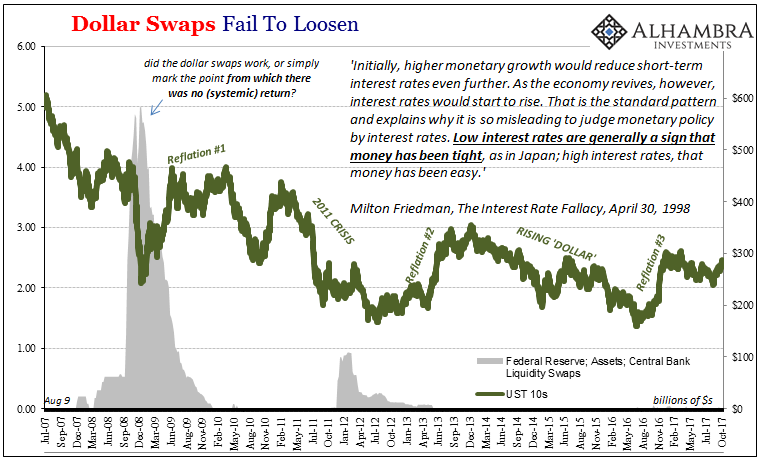

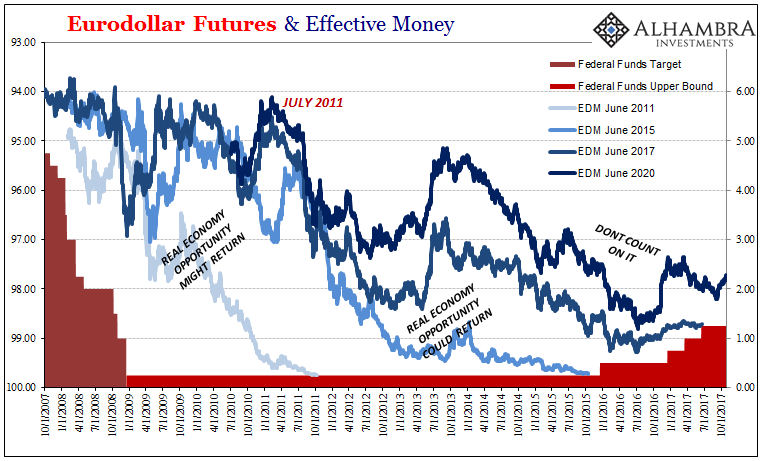

It’s a question that the Fed and the mainstream still struggle with today. Yellen will leave her office in a state of “conundrum”, just as Greenspan left if for Bernanke. If the economy was actually close or better on inflation and unemployment, there would be no bond market contradiction.

And it’s not actually a contradiction so much as a performance grade, and a failing one for Yellen/Bernanke. Fed officials claim things are getting better where instead the bond market just flat out disagrees. Long term yields, inflation expectations (TIPS), and implied future money rates (eurodollar futures and interest rate swaps) all signal nothing has changed, and that’s not good.

Naturally, Economists aren’t willing to let any market spit in their face. So the Fed has done what the Fed always does, which is to author a statistical study for why interest rates aren’t so Yellen-friendly. As usual, it’s San Francisco Fed President John Williams at the forefront, and also as usual he’s figuring his R* prominently in the discussion.

You can read his study here, but it really doesn’t offer anything different. He talks about the signal channel (and actually refutes Bernanke’s claim on that account) as well as, as always, term premiums. When in doubt, Economists will turn to this made-up Fisherian deconstruction regression in order to justify what in plain English is really, really simple.

The flat yield curve at these nominal rates says the Fed got it all wrong. Trying to claim lower term premiums instead as a reason is trying to weasel toward a conclusion where the Fed didn’t get it all wrong, and thus might in the near-term be right about something.

Like cherry picking 2009 for a start date in evaluating the labor market, term premiums are a sign that you really don’t have a good explanation. Despite that, Williams leaves his paper in very familiar territory:

Similarly, if investors’ expectations about the Fed’s balance sheet were to change suddenly, or if investor sentiment about the relative attractiveness of Treasuries deteriorated for other reasons, the term premium could rise quickly. Hence there is some risk of rising Treasury yields, which some may view with concern given that high values in equity and other markets are partially based on low interest rates.

After all that trying to make sense of how Economists just don’t get the bond market, he still finishes with the usual “bonds could be wrong” scenario. That’s why the placement of lower nominal yields into the term premiums category. If it was instead due to lower inflation expectations or reduced projections for short-term largely money rates (as is actually the case, again using market-based data such as TIPS and eurodollar futures) there would be no possible way to reach that conclusion.

The bond market is clearly, CLEARLY, stating that it doesn’t believe, just as it hasn’t for years, the economy is going to get any better. That just can’t be, so term premiums yet again. Some people actually believe this is a science.

Stay In Touch