If China wishes to ever throw off the shackles of the eurodollar system, and they do, to eventually go out on its own in an RMB dominated world there is a lot to cleanup long before that’s ever an attainable goal. To start with, we don’t know near enough about what’s going on inside that country’s financial and economic system. It would be a problem in any format, but inside one that has grown so far so fast it creates too much of an abiding interest in the darkside (exactly the eurodollar’s big problem).

To replace the “dollar” one must first offer to fix what’s broken, or at least realistically propose to overcome the current range of flaws (which are many). Information asymmetry is a deep and foreboding element intrinsically linked to how the eurodollar evolved. China’s yuan is simply too late to attempt to repeat the process.

As much as the Chinese system remains traditional, there is a lot about it that evokes the shadows of the West. Indeed, in RMB there is its own shadow system that is a relatively new phenomenon. Because of that, not much is known or understood about how it all fits together. That’s another big problem that inhibited the eurodollar’s recovery, for everyone had some idea what was going on in the shadows as far as trades and activities, but what wasn’t known was how all those individual connections made a big difference in the reverse.

One of those “dollar” connections was with China itself. Even after 2008, eurodollars flowed east (through Tokyo) and into the Middle Kingdom. Like peak housing bubble rationalizations, so long as China was growing nobody really cared about how the RMB sausage was made. Once China stopped growing, around 2012-13, suddenly risk mattered (just like once the housing market stopped, suddenly people started to care about things like subprime rehypothecated repo). As attention to risk grew, “dollar” flow quite naturally reacted in the inverse.

Unlike the eurodollar, however, RMB hasn’t yet undergone even a partial reckoning. There was no mass of defaults, no grand illiquidity episode that threatened China’s banking system to its core. It all came close to something like that in 2015-16, pulling back from the prospective brink just far enough. Rather than successfully end all questions, now raised the threat still lingers in popular imagination because the math, even partial as it is, doesn’t work out favorably over the long run. There is too much Japan to China.

China is often a maze of contradictions just like Japan used to be. This time, and what may be keeping China Inc. afloat so far, a lot of its big business is inextricably connected to the government at all levels. Sometimes failure really isn’t an option.

But all that does is create a bias the other way, an embedded TBTF ideal that seeps into everything and anything.

One relatedly tangled corporate web that keeps coming up lately is HNA. The conglomerate was at one time a dinky airline operator. Then it went nuts, borrowing and buying as many foreign assets as it could possible get its hands on. It became, in essence, China’s Poster Boy for byzantine corporate structures whose ultimate object isn’t truly known; but what sure seems like a scheme to cash in on RMB shadows for funding capital flow to the rest of the world.

The company is having liquidity problems, or at the very least there are persisting rumors to that effect. On November 2, the company floated $300mm one-year notes at a preposterous (for these days) 8.875% (that still attracted $700mm in order interest). Yesterday, Bloomberg reported that HNA Aviation, a subsidiary, is having trouble paying on Bankers Acceptances. Anyone who knows Chinese money and shadow money immediately recognizes the red flags, and the game.

Bankers Acceptances are like something out of a 19th century British novel. They were once the primary source of trade financing, a strength in sterling that the Federal Reserve was created in one big part to compete with (for the dollar). Supplanted a long time ago by the eurodollar system, acceptances are still a significant outlet for and of Chinese money.

They work like a kind of cashier’s check, ostensibly for financing trade. If you are in China and intend to import goods from someplace else (in or outside China), you deposit funds, take your acceptance and go get those goods on whatever market. The acceptance expires at a known date, meaning that the company selling goods to you knows that it will get paid at that time by the bank issuing the paper. It will release the goods upon obtaining the acceptance, finance greasing the wheels of commerce.

In the meantime, however, the company is free to sell the acceptance to whomever else might want it – but at a discount. The Bank of England and later the Federal Reserve used to operate heavily in acceptance markets (by discounting at a specific rate set by monetary policy) in order to ensure smooth liquidity and function so as to make them perfectly “acceptable” to any foreign hands.

The Chinese acceptance market is, or can be, a little different. Due to often strict banking rules, they have become a secondary currency that doesn’t count on bank balance sheets (China’s anachronistic version of footnote money, though I don’t believe they show up even in the footnotes of Chinese firms). A company in one Chinese province can agree to sell RMB 100 of goods to another firm in another province, the latter who agrees to sell RMB 100 of the same or similar goods back to the former. Both transactions are put up at a Chinese bank, and for no real economic activity both companies now have combined RMB 200 in quasi-money.

Those acceptances can be sold on the market for actual RMB cash, off the books, but again at a discount. At one time it had become almost a cottage industry, brokers sprung up whose primary purpose was to match banks with those willing to engage in what amounts to a reverse repo (don’t ask) using acceptances in order to avoid onerous bank regulations. Chinese regulators have attempted several times to address what is often thought to be widespread abuse, in this way and as described above.

The bigger problem, however, for anyone constantly selling them at a discount is that acceptances become a costly source of cash. Eventually, those costs add up and they can add up big time if the acceptance market isn’t so liquid. Such as:

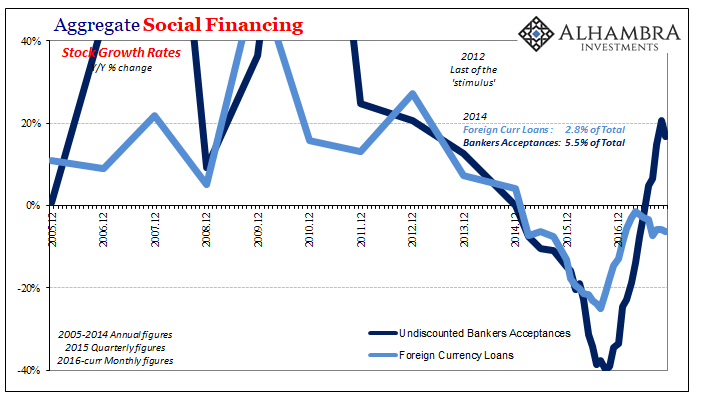

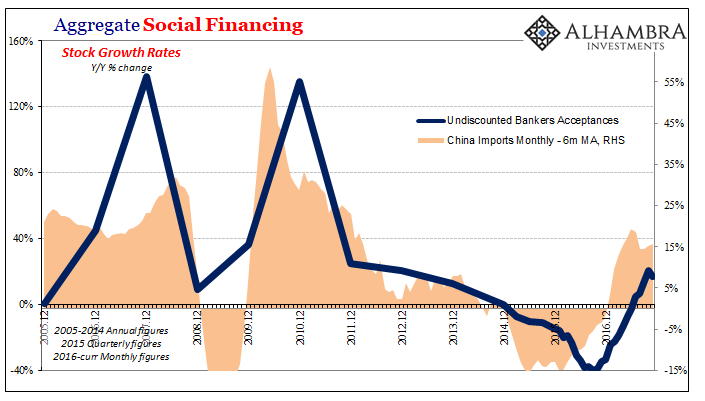

In late 2011, issuers of Undiscounted Bankers Acceptances, one piece of China’s Total Social Financing money/credit aggregate, began to be less enthusiastic about the practices both legal and otherwise. That year, Chinese bank authorities had issued strong warnings about especially the reverse repo charade.

More than any stern cautioning from officials, though, the acceptance market began to wane simply because Chinese commerce did.

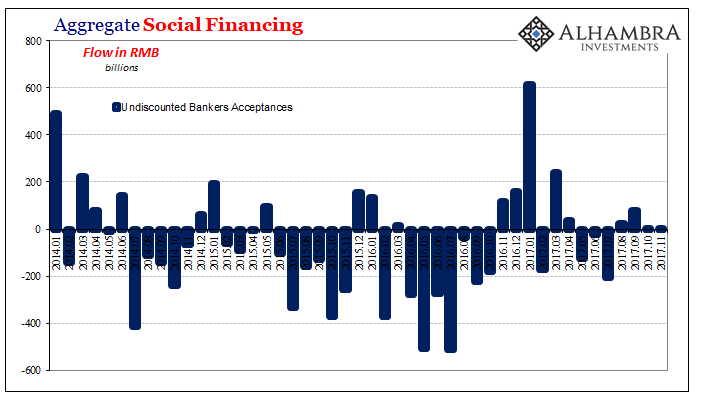

Unsurprisingly, the trend in quasi-trade money follows inbound Chinese trade. After a few very bad years, it meant a revival of that market starting late 2016, a monetary “reflation” in arcane China money alongside the more conventional rebounds elsewhere. The PBOC estimates that flow in Undiscounted Bankers Acceptances was a rather robust positive RMB 600 billion in January 2017 – a third consecutive month of substantial growth.

That revitalization, however, didn’t last all that long. The PBOC figures show that while acceptances aren’t falling off like they did in 2014-16, they aren’t growing much anymore in 2017, either. As much as Chinese trade has come back, it really hasn’t come back.

If HNA saw that burst of acceptance activity as a way to raise funds quickly for whatever other liquidity problems it might have been having, and thought that it represented just the start of an economic resurrection, then that would explain their more recent troubles in that space. Like practically everyone else, they probably thought China and the world economy was set to take off on globally synchronized growth. It didn’t, acceptances didn’t, and the funding squeeze though relatively better is as likely to resume.

HNA Aviation Group Co. has had trouble paying bankers’ acceptances — debt instruments that mature in the short term — and Citic Bank is working with HNA Group to try to resolve the situation, the Chinese lender said in a statement sent exclusively to Bloomberg News this weekend. The group has several bonds and loans from multiple banks maturing at similar times, causing a “temporary liquidity” issue, Citic Bank said.

It’s easy to make too much out of one anecdote whose struggles may be attributable instead to its own idiosyncrasies rather than systemic factors. Still, what HNA’s recent experience maybe highlights are these hidden monetary risks in China that, coupled with massive leverage, make for some rational uncertainty (to put it mildly). That’s a lot to ask for in seeking more “dollars”, and too much to ask in seeking to replace “dollars” unilaterally.

It is, for me, quite illuminating that in the middle of 2017 when things were all supposed to be going right again that the PBOC became so invested (directly or indirectly) trying to fool the world into believing its “dollar” problems were all in the past by engaging in a haphazard, ad hoc Hong Kong bypass.

It suggests, strongly, that though China wants more “dollars” for as long as it has to be stuck here with them, the eurodollar system as a whole (via Japan or not) is now keenly aware of the risks involved with funding Chinese interests. Like the eurodollar itself, it may be that there is just no returning to a pre-enlightened state; once you see it for how it really is, you can’t just go back to sleep and embrace the dream. If “dollar” holders continue to be wary, what might that might make prospective “dollar” replacements?

It certainly would fall right in line with both Xi Jinping’s recently hardwired Party Congress ideals as well as PBOC Governor Zhou Xiaochuan’s early November warning. As the latter wrote,

“…hidden, complex, sudden, contagious and hazardous.”

The eurodollar doesn’t really work any longer, but it at least keeps the lights on (this is not a defense of it, rather it’s recognizing the inertia behind why it has lingered on this way after so long). The idea of economic growth is preserved in it, if no actual growth is ever derived from it. From the perspective of the global banking and more so political system, better the devil you know?

Stay In Touch