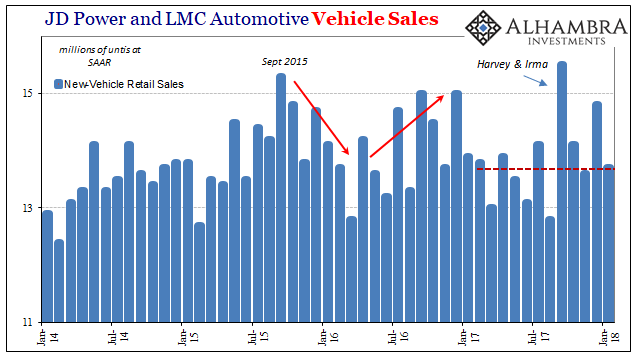

The storm-assisted car-fest that ended last year appears to be fully winding down. Automakers overall posted weak sales to start 2018. They are putting on their best face, admitting widely that this year was going to be a tough one anyway as if they expected it.

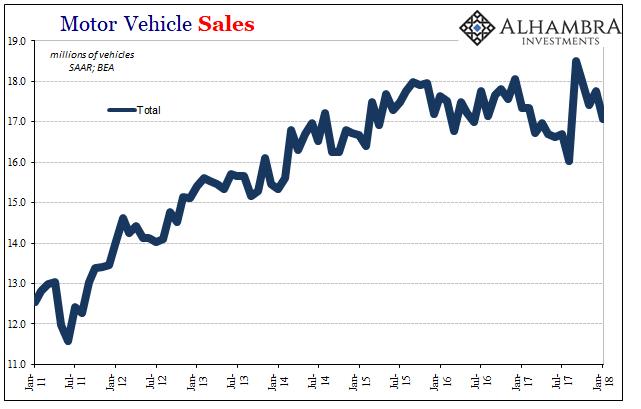

According to the Bureau of Economic Analysis, total sales (seasonally-adjusted) in January 2018 were 17.1 million, down from 17.8 million in December. It was in September and October where car sales picked up dramatically from mid-year when a clear downward trend had developed. The issue for this year is how much of an effect Harvey and Irma had, and whether it will be more than temporary given the inventory situation.

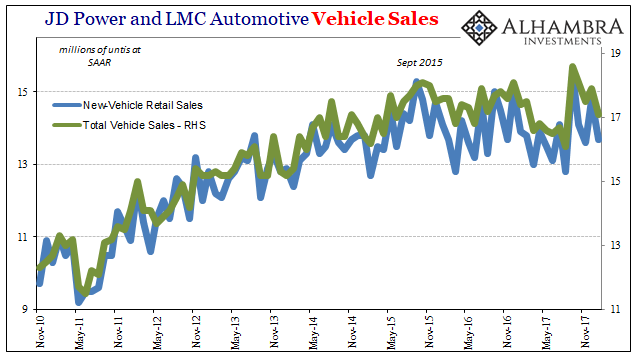

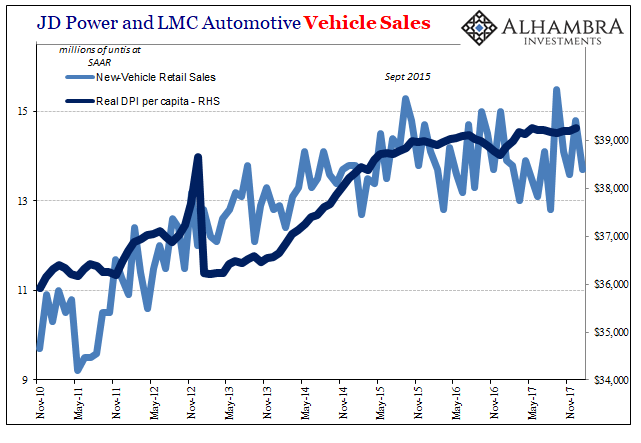

Estimates according to JD Power/LMC as well as those from AutoTrader are not encouraging. Both are heading quickly back to more middle 2017 levels than those picked up in late year.

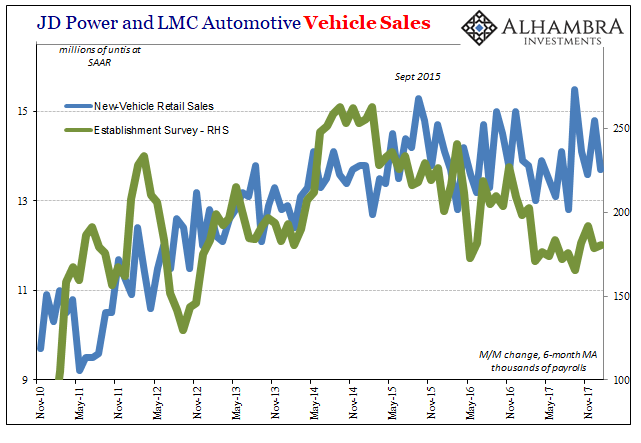

The growth trend ended in mid- to late-2015, an inarguable macro-related inflection. It was and is a surprise to economists, including those working at the automakers (who keep saying things like “robust job market”). To the BLS, of course, the clear and persistent slowdown in the labor market offers instead an economic explanation far more consistent with these hard(er) figures.

The problem now for the manufacturers is incentives. Each of them has produced heavier and heavier programs just to keep sales from falling further. That has an impact on profitability, a factor that is taking on paramount importance particularly at domestic carmakers.

“In the face of very high consumer confidence, low interest rates, low gas prices, longer and longer loan terms, we’re still seeing the pedal through the floorboards on incentives,” said Mark Wakefield, head of the auto practice at consultant AlixPartners. “You’re training consumers to look for the deal.”

That’s one way to look at, the one where the unemployment rate describes the economy for you. Another and again more consistent way is to understand that all the rest of the labor market data is the reason “high consumer confidence, low interest rates, low gas prices” aren’t enough for automakers to be able to reduce incentives. There is no boom, at least not for American workers.

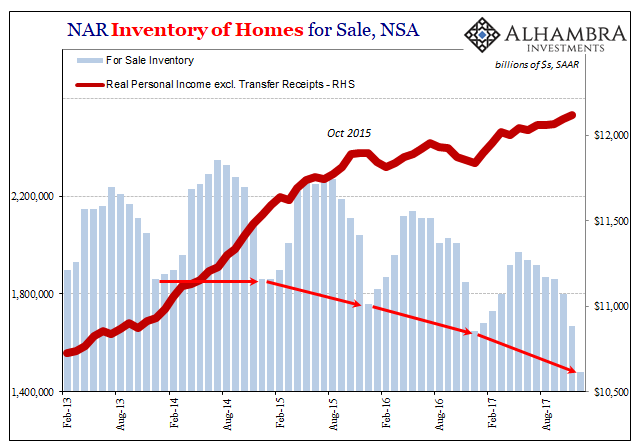

Customers haven’t been “trained” to look for huge deals on new stock, without the incentives they won’t pull the trigger. For the same reasons we see available-for-sale housing inventory steadily decline, consumers particularly at the lower ends of the income table are for more uncertain about the economic climate and therefore their future in it. Give them the deal of a lifetime, or forget about it. Even those who are given the opportunity are refusing, which is the prior downtrend to the middle of last year. If we go back to that trend, then it’s bad news all around.

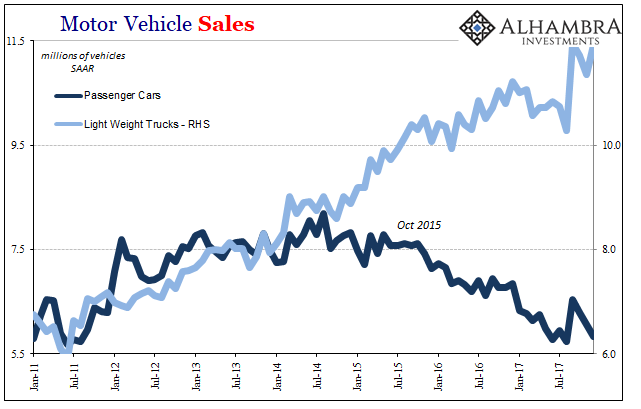

That’s one reason why car sales as opposed to those of SUV’s and pickups have crashed. At the lower ends (cars are much cheaper relative to light trucks), there isn’t a whole lot of demand going back to around late 2014 – exactly the time housing inventory began to fall off. Increasingly concerned about work, at widening margins Americans don’t want to add new payments whether in a new car or because moving to a bigger and more expensive house (with its higher mortgage payment despite, too, “low interest rates”).

Sales at GM rose just 1.3% year-over-year, fell 6.3% for Ford, and declined 13% at FCA (the seventeenth consecutive month of declines). Toyota’s overall sales rose 17% on the strength of a redesigned Camry gambling on increased market share for the Japanese manufacturer in a declining car market, while falling 1.7% for Honda. Nissan achieved a rise of 10% and Hyundai-Kia sales fell 6.4%.

If dealers can’t clear any additional inventory than what Harvey and Irma were able to, which is what incentive payments to customers are supposed to be for, then production has to be further adjusted. It would add yet another headwind to this boom that has yet to boom.

Stay In Touch