What happened to the recovery? It’s a complex question with a surprisingly simple answer. The density of the topic, particularly entangled as it was in close proximity to the calamity of the Great “Recession”, clouded the diagnosis. If you ask ten different academic economists you might get ten different answers, though I suspect seven or eight of them would be variations on one general theme.

Writing in November 2015, New York Times political columnist Paul Krugman (he long ago departed economics) summed up this alternate theory:

For those who don’t remember (it’s hard to believe how long this has gone on): In 2010, more or less suddenly, the policy elite on both sides of the Atlantic decided to stop worrying about unemployment and start worrying about budget deficits instead.

This shift wasn’t driven by evidence or careful analysis. In fact, it was very much at odds with basic economics.

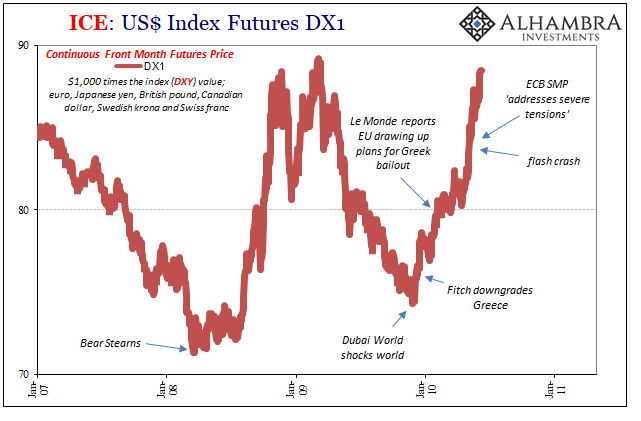

There is a lot of truth in what he writes, which is precisely the problem. Left out of his glancing analysis is what exactly caused this change in 2010. Greece was on everyone’s mind for a reason, which for government officials was a very real fear of being forced to follow in that country’s footsteps toward insolvency, bailout, and worse.

In the Krugman formulation, the wave of “austerity” that gripped the world was the end of the recovery. As he saw it, and still does, the failure of governments to come to grips with the scale of the problem meant a failure to appreciate the econometric concept of hysteresis.

The idea of hysteresis is also quite simple, but in practice it is one of those more absurd concepts that Economists often cite when they can’t site themselves. As in the physical world, it takes some great exertion at the start of a process in order to get it all moving. To overcome inertia, a far higher force must be applied at the beginning than later onward after things are rolling.

In Economics, the economy in recession or worse lingering in an ocean of negative factors is one where governments must prioritize “stimulus” no matter any other factor. Bond vigilantes aren’t to be feared at this moment, rather ignored in favor of all-hands-on-deck fiscal profligacy. There is no deficit too big in this situation.

In practice, however, that’s not how it goes. For one, how big is “big enough?” In truth, Economists like Paul Krugman can’t (ever) answer that question. Even in 2009, though there was a general sense that the massive Stimulus Bill (ARRA) was sufficiently large, there was still a palpable unease that nobody really knew (Krugman included). How can you contemplate deficits and everything if you have no idea how much government spending might be needed from the very start?

For most Economists, it devolves into an ad hoc process – which is exactly what governments had begun to reject. In other words, from the Krugman view the government should start spending big and then just keep on going until it works. If it fails after the first year, do more the next. And if it fails after the second year, well, maybe twice or three times more the third. The key is, apparently, that you can never stop.

You can see the problem from just a rational perspective. “Stimulus” becomes a sort of infinite loop, catching anyone so ideologically blinded in a trap because Economists from the very start always, always assume it works. Maybe government spending doesn’t, and that governments who have to operate under actual, real constraint (taxes and borrowing) should be given the leeway to recognize this stark reality. If fiscal destruction doesn’t bring about the intended economic benefits, continued fiscal destruction really doesn’t make any sense. True science begins with falsification.

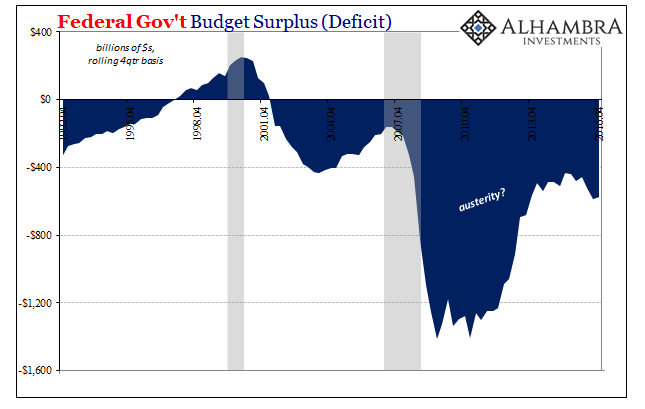

The word “austerity” itself has thus come to mean something very different than its actual definition. What it really indicates, and why Economists so despise it, is to reject Economics’ recommendations about how effective fiscal “stimulus” can be. Its not about cutting back spending in absolute terms, rather it’s about scaling back from the total absurdity of an open-ended commitment where you can never admit it doesn’t work.

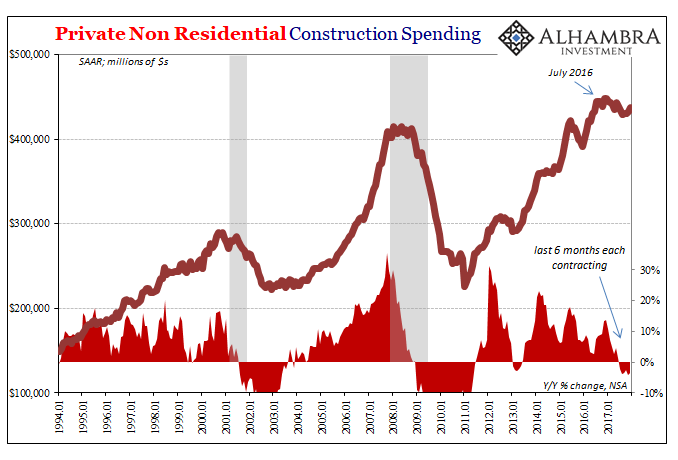

And the federal government has the luxury of debt funding that others do not. State and local governments, for example, are not afforded the almost blank check the feds are. It’s been far more difficult in the wake of the housing bust for the municipal levels to adjust.

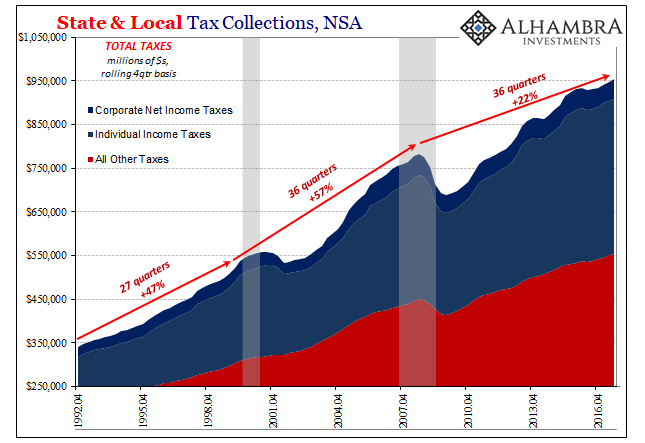

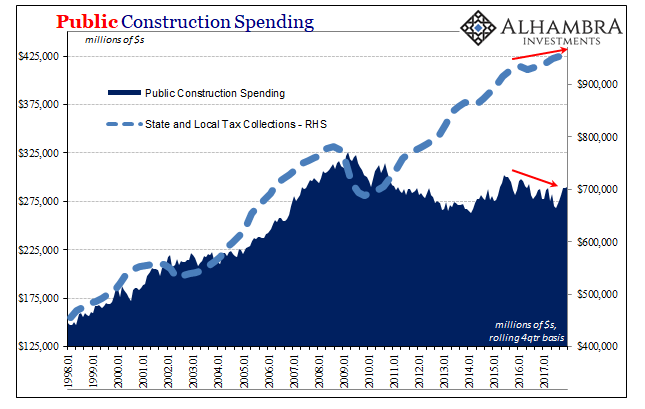

Since Q3 2008, the Census Bureau estimates that State and Local tax collections have risen by 22%. That sounds impressive until you realize the length of time involved – 36 quarters (through Q3 2017), or nine years. In the preceding nine years, from Q3 1999 to Q3 2008, a period which also included a recession toward the front, State and Local Tax Collections increased by 57%.

That’s one part the lingering aftereffects of the housing bust, where municipalities in particular were unable to find other sources of taxation once housing values declined, and new home construction stagnated overall. It’s not the only reason, however.

Whether income or corporate taxes, and even the various other non-real estate excises, there has been lethargy in the US tax base. As a result, municipal governments have had to exercise enormous restraint. Budgets do not grow as they once did, as a result projects get shelved and canceled.

At the state and local level, this is actual austerity. It is, in fact, a clear economic drag.

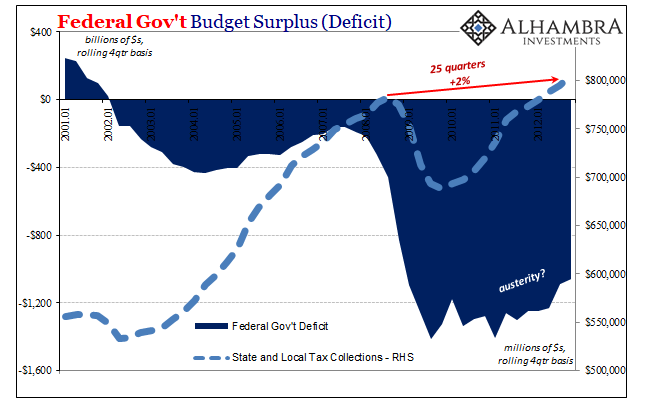

What Krugman has constantly advised is the federal government stepping in and doing far more than it did to make up for this economy-wide “headwind.” What tax collections instead propose is that all prior “stimulus”, including the QE’s and those other of the monetary variety, simply didn’t work. The federal government spent far outside of all prior boundaries, as did the Federal Reserve in operating in ways that in early 2007 would have been thought totally insane.

You can’t fake tax collections, and had those initial runs of “stimulus” in 2009, 2010, and 2011 actually achieved significant economic progress then there never would have been a slowdown in 2012 and beyond. It is perfectly rational that municipal governments in particular might have continued on with austerity because the recovery Economists had kept promising just never materialized.

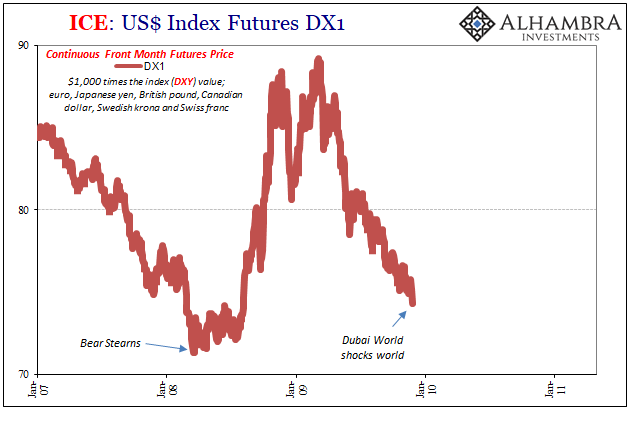

Krugman’s view fundamentally misdiagnosis not just the effectiveness of orthodox intervention, but also what started going wrong in 2010 (actually November 2009). He, and those like him, believe it was bond vigilantes that scared everyone into his version of austerity. It wasn’t.

The issue has always been much simpler; money. The reason Economists can’t calculate an accurate “stimulus” program with respect to hysteresis is that they don’t consider the monetary variable to have been germane. Central banks are and have been “printing money” so, for them, that can’t be it.

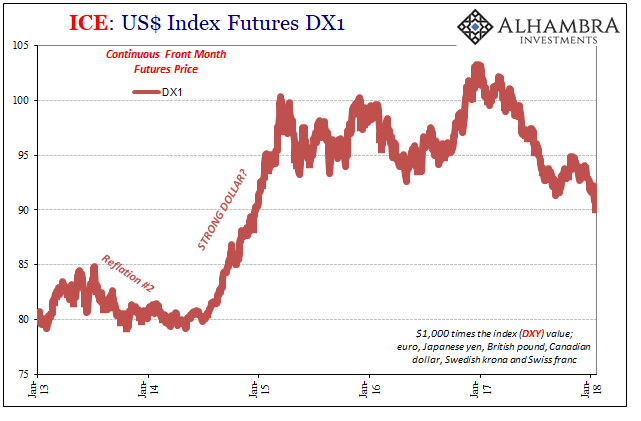

No matter how much the dollar “rises”, they fail to make the connection. It wasn’t ever really about Greece but the eurodollar system. Austerity in this post-crisis view is really about “stimulus” that can never overcome the monetary drag. That’s the verdict that businesses have come to adopt, too, as they now discount more and more the mainstream proclamations about unquestionable but always future optimism. In the US, as elsewhere, they are avoiding productive investment, particularly again in the past few years in the aftermath from where the “dollar” truly “rose.”

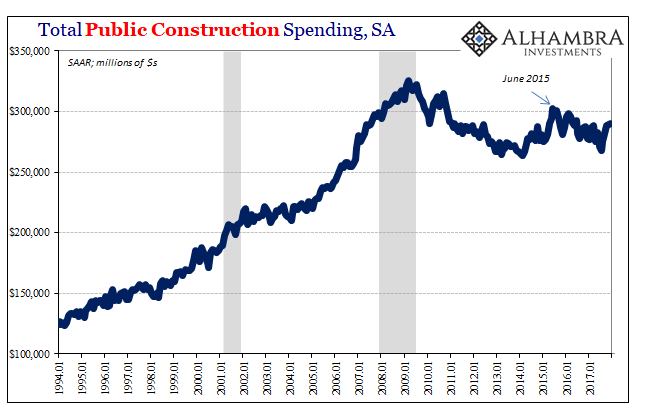

It’s the same reason why state and local construction spending has been falling since the middle of 2015 – their tax collections in the aggregate have been off since around the same time because the economy for a third time not only failed to respond to continuous “stimulus” but in addition was subjected to still another downturn Economists can’t explain or even bother trying to.

What’s left is prospective policy whereby the object is not unfettered government spending or the pop psychology of a QE, rather it is one that seeks at all costs to stop the “dollar” from rising. That’s a far different proposition, one focused on stability, which explains a whole lot about the last ten years starting with the failure of “stimulus” to achieve hysteresis.

In 2018, of course, we have fallen once more into the big trap. The “dollar” is no longer rising and is, in fact, dropping precipitously, so what’s the point now? Economists have once again started to believe all the “stimulus” did work, it just took a long time for the results to stand out. Even things like productive investment that on its own would seem to suggest a very high degree of significant caution will in this view just switch to a much better trend because.

Globally synchronized growth is upon us, they say, so all our worries are over, no reason to re-litigate the past economic debates. It’s a straight line out of austerity to prosperity from here, right?

Stay In Touch