It’s impossible to tell what drives the short run in anything, so anything we describe and attempt to ascribe moves to comes with a grain of salt. That said, there are clearly some things missing here. I’m not talking about big stuff like overrating the Fed’s predictive abilities and its resolve, ridiculous stock valuations, or anything of the like.

Stocks peaked on Friday, January 26. The following Monday, they hit a small pocket of more intense selling late in the day, the sort of liquidation trend that has become more apparent this week.

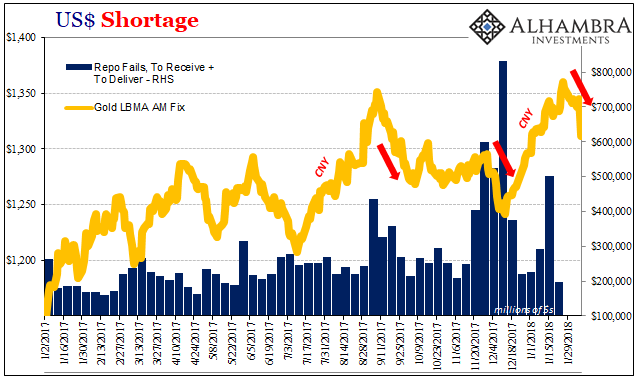

Gold peaked on January 25. It was down about $6 that Friday (26th) and then another $6 the next Monday (29th). When we see these sorts of gold pukes we immediately think of repo. Over the past year, repo and collateral difficulties suggest T-bills. In other words, throughout 2017 there was a clear and intuitive relationship between especially the 4-week bill equivalent yield in discount to the supposed monetary “floor” of the RRP, and repo market collateral problems.

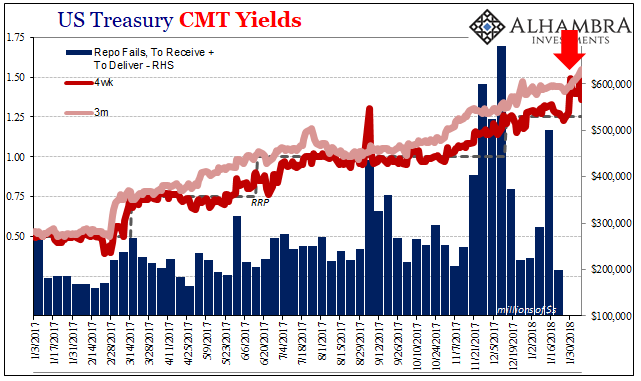

A premium paid for bills is nothing other than a shortage of collateral. Thus, given the setup I describe above, we should have expected to find last week and this week the 4-week bill yield challenging and subverting the RRP, right? No.

Somebody on Tuesday, January 30, was forced to liquidate 4-week bills in serious fashion. The equivalent yield was 1.28% last Monday, and below the “floor” (1.25%) on both Thursday the 25th (1.23%) and Friday the 26th (1.24%). By the end of trading on the 30th, the yield was instead 1.49%, or about where it would have been had the Fed “raised rates” at that policy meeting.

The vote for another rate increase was not held until the 31st, so it is possible that the bond market was anticipating a surprise decision. The fact that the 3-month bill didn’t move much, and that the 4-week bill surpassed it, however, argues that this had nothing to do with Janet Yellen’s last activities.

Some might argue fears over the debt ceiling and the federal government perhaps unable to pass continuing budget resolutions, and maybe that was true, too. But we’ve seen this before, in early September if you recall.

It appears to have been a liquidation of bills, but why? Or perhaps, who?

Now China’s boldest dealmaker, with more than $40 billion of acquisitions spanning six continents, faces growing regulatory scrutiny from Beijing that threatens to spook bond investors and raise HNA’s financing costs when most of the shares pledged to fund its buying spree are declining. If the value of its collateral falls enough, HNA could be forced to sell its holdings to repay debt.

HNA’s debt crunch has only worsened since that story ran last July. Though a Chinese conglomerate, there really is no seeming end to that company’s reach into areas such as global finance. This one company is, sometimes you have to just laugh, among the largest shareholders of Deutsche Bank.

That doesn’t mean that DB is directly responsible for the recklessness of HNA and its growing liquidity crunch, and is therefore exposed, but it does add another element to consider for things like collateral. It’s not just DB shares that HNA has pledged for short-term loans, the company has also put up shares in one of China’s largest banks, too.

Despite the company’s claims it has a handle on its liquidity situation, earlier in January it was reported that HNA missed more payments that were due late last year.

Underscoring the fluidity of the situation, one of the banks recently reopened some credit lines after certain HNA units posted additional collateral, one of the people said. And China Development Bank Co. last month granted HNA a credit line of at least 5 billion yuan ($771 million), of which 2 billion yuan has been drawn down, another person said.

On January 31, curious, further news broke that the company had told creditors it would begin selling off about $16 billion in overseas assets. Most of those were to take place in Q2, about 80% an unnamed source said, leaving some total of unknown possessions to be taken care of either after that, or perhaps before.

HNA isn’t the only one. On January 30, more curious, the Chinese government announced it was seeking a sale for Anbang Insurance Group. Regulators had been probing that company, another conglomerate which like HNA had been binging on overseas assets, for several months. Unlike HNA, Anbang’s focus is mostly financial in nature, with businesses in insurance, asset management, and banking.

There is a decidedly Japanese flavor to these multinationals and what they are attempting, or were. Like the keiretsu that ultimately drove Japan Inc toward now three lost decades, leaving in their wake a massive dollar (synthetic) short the country has never overcome (how could it?), what these Chinese have been up to evokes 1980’s Japanese urges.

I wrote all the way back in March 2014 that it really seemed like the parallels were all there, striking as they were then they have only grown in the almost four years since (monetary time moves much slower in the 21st century, though we often think the opposite).

What we can take away from all this is that China is one massive mess of dollar entanglements, cornered by an export focus that won’t recycle to the previous peak, further wrapped inside a credit bubble beginning to show signs of cracking. The “usual” remedy for such a system is to try to “export your way out of it.” And that may be the forward intent if it doesn’t get too complicated by eurodollar mechanisms ahead, but it also may signal a far darker worst case (that may be more probable than anyone admits now) – China in 2014 is Japan in 1989. There are enormous similarities that make such a comparison compelling, enough to further study how that analogy might work out alongside their differences.

I’ve also written consistently that I believe Chinese officials are more than aware of the dangers, and similarities, to being Japan 1989 (or just 1985). I think it explains a lot about why they have taken a more considered approach since 2013 even though it has led them to such great damage and decline. They may fear what would be an even worse situation, like Japan 1990, should it all spiral out of control. Better a controlled deceleration than a spectacular blowup, or so in theory.

In addition to those two mentioned above, Fosun International, Dalian Wanda, and Changxing Ltd. have all come under intense scrutiny since last summer. These five firms had accounted for an estimated 16% of all overseas investments made by Chinese companies between the start of 2015 and June 2017.

On June 6, 2017, it was rumored that China’s Banking Regulatory Commission demanded what were characterized by those rumors as “urgent” conference calls with the largest of China’s banks. At issue: increasing leverage used by these firms in particular, and the way in which it was booked, deployed, and perhaps misunderstood or underappreciated.

Bank of China was reported to have started selling bonds obliged to Wanda almost immediately, leading to a plunge in the company’s shares and its bond prices. Management denied that was the case.

All of this mystery and speculation was followed by both President Xi Jinping’s 19th Communist Party address and more so PBOC Governor Zhou Xiaochuan’s cryptic early November warning. The latter noted repeatedly the danger to China via leverage, as I wrote at the time:

So what does Zhou have to say this time? Quite a bit, as it turns out, including a lot that he has already said before. Unlike Western central bankers, the PBOC head isn’t afraid to use the term “bubble”, or whatever the Chinese word might be for it. China has a debt problem, a macro leverage ratio of 247% (that we know of) Governor Zhou was careful to highlight.

So much leverage and debt, however, are symptoms of other imbalances. His essay was pointed in describing the PBOC’s tasks in those terms, “prevention and control of financial risks should be based on both the symptoms and the root cause, taking the initiative to attack and defend and actively respond to both.”

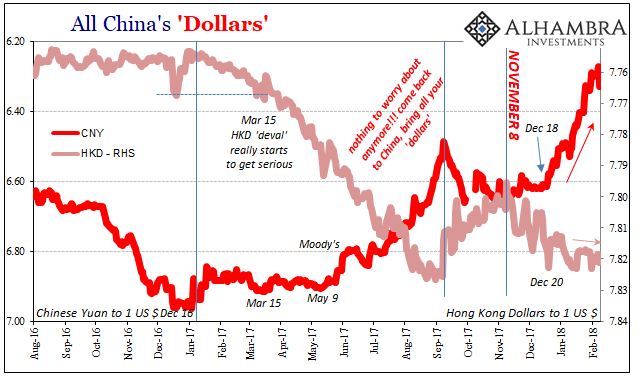

We are left asking ourselves several questions, primary among them, why the urgency in using Hong Kong to lift CNY as far as it has gone? If what we are seeing is just part of the story, it would make quite a lot of sense to fortify China’s position as much as possible ahead of what might be some very rocky days ahead. As Zhou put it (or at least how it was translated):

Overall, the financial situation in our country is good. However, at present and for a period in the future, China’s financial sector is still in a period of high risk-prone period [sic]. Under the pressure of multiple factors at home and abroad, the risks are wide and varied, presenting invisibility, complexity and suddenness, contagious, harmful characteristics, prominent structural imbalances, illegal and disorderly chaos, potential risks and hidden dangers are accumulating, and the vulnerability obviously increases.

Somebody has been caught liquidating recently, and it appears they are either still at it or because it was so disruptive it may have triggered severe aftershocks (low liquidity) all around the world. We don’t really know who, how, why, or where. It doesn’t, however, stop us from speculating.

Stay In Touch