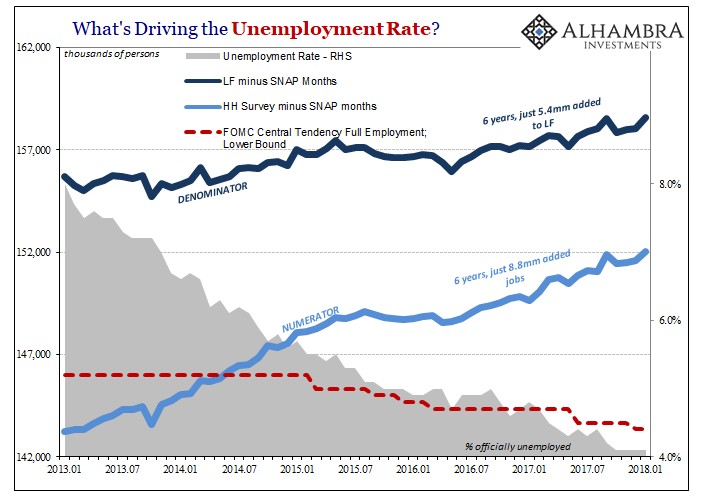

The Fed in its Beige Book as well as in the speeches of several of its officials has referenced a labor shortage for years now. On the one hand, that is understandable given the trajectory of the unemployment rate. All the way back in 2013, during the so-called taper tantrum, it was the rapid drop in that rate which triggered (supposedly) the violent reaction. Because it had fallen much faster than anticipated even by those otherwise permanently optimistic, there was, we were told, no choice for the FOMC other than to speed up their planned exit program.

The intended sequence of events is easily established; the end of slack, the increase in wages, businesses passing along those cost inputs to consumers, and workers who can afford the price increases because of rising wages and aggregate labor income (recovery). During that process, the central bank’s central task is to make sure it doesn’t get out of hand. Like some sort of twisted referee, Economics doesn’t like it when things become too good for workers.

As easy as it sounds in theory, in practice it is near impossible. There are any number of problems starting with measurements and statistics. Even if those could be more understandably overcome, there is left the non-trivial detail that in truth nobody really knows how these things work. We have a rough idea of some basic causes and effects, but the complex interplay between so many variables is beyond any current human capabilities.

Holding fast to that expected process anyway, the Federal Reserve has tried repeatedly to gauge where in it the US economy falls. As noted above, given that they have been talking about the low unemployment rate as well as a labor shortage for years it’s safe to conclude they really have no idea.

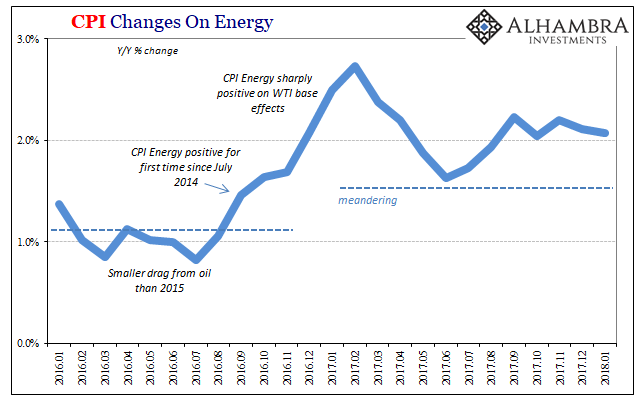

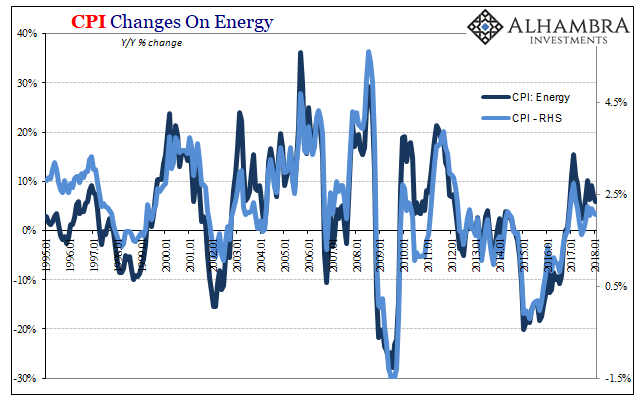

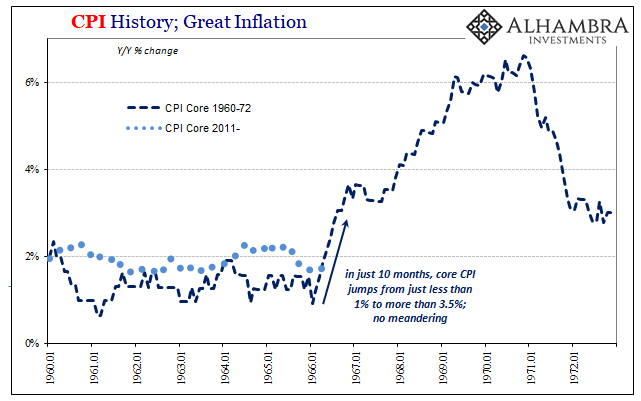

In the past, that’s not how it ever went. When inflation came on, it came on. There was no meandering nor questions about this or that. Consumer prices started to rise, and then they rose some more, and some more, and then spiraled from there (or triggered a true inflationary peak, meaning recession). The media keeps talking as if this was the case today, except there has been but one acceleration in the CPI (or PCE Deflator) attributable entirely to the rise of oil prices from the ugly lows of the “rising dollar” downturn.

We’ve been left waiting for more than a year for the predicted next leg up.

As I’ve stated more frequently, the more time passes where what’s supposed to happen doesn’t, the more certain those who believe these things are that it’s right in front of us. And yet, it never is.

The inflationary boom narrative is one without any inflation. The latest CPI statistics merely confirm that nothing has changed. That’s a big problem for the mainstream forecast because for it be valid something big has to change; and soon.

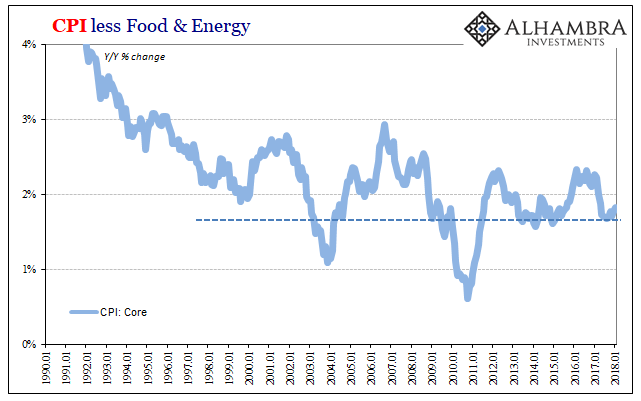

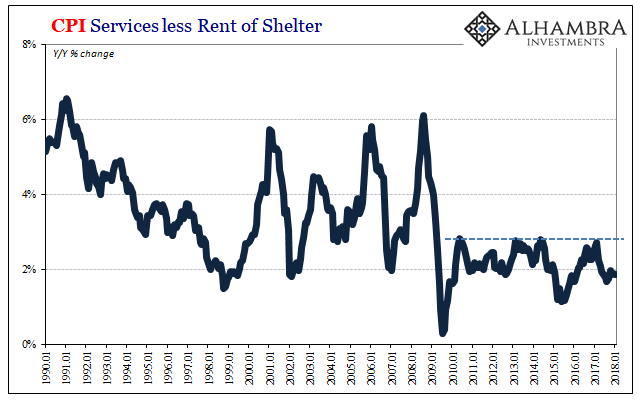

The headline inflation rate was 2.07% in January 2018, down slightly from December (2.11%) and November (2.20%). More important, there still isn’t the smallest hint that anything is different. All the main “core” versions, such as CPI Services less Rent of Shelter, continue to come in at the lower ends.

Ultimately, that’s what inflation is. It’s a difficult concept made all the more so because of how it’s been calculated (the basket approach of an “average” urban consumer) and re-calculated (switching to the PCE Deflator). There is an appearance of precision that just isn’t warranted. Nor does the CPI or PCE Deflator index often match people’s perceptions of price changes.

Inflation is broad-based consumer price changes. To channel Bill Dudley’s clumsy formulation from March 2011, if the price of an iPad is lower (or you get a lot more for the same cost) even if food inflation is palpably stinging, ultimately there is doubt as to Milton Friedman’s apt summation; inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon. To paraphrase Churchill, the CPI is the worst inflation measure except all others that have been tried.

Because of that, we don’t count on precision but use it to add to our analysis of broader conditions. In other words, if everyone is convinced that an inflationary boom is forming right now, then it better show up somewhere. Not in some minor uptick in one single month, to be undone immediately the next, but a clear upward pointing arrow that establishes at least a reasonably arguable foundation for the expectation.

Given that inflation is a partial check on monetary conditions in the real economy, what we know of the hardships in the eurodollar system has always kept the inflation scenario as the least likely. That’s as true during the upturns like in early 2011 when Dudley angered so many folks, importantly as he was just about to be once more caught completely off guard by another serious and global “dollar” squeeze, as any other such as the current one.

For the inflation scenario to become an even or better bet, it would mean a radical change to fundamental monetary propositions. What rational basis exists today for that? The fact that the CPI now one month into 2018 still doesn’t measure, even crudely, that trajectory isn’t surprising at all.

Still, as yet another month goes by without the expected surge, the more next month is guaranteed to be the one. The only thing booming is the hysteria.

Stay In Touch