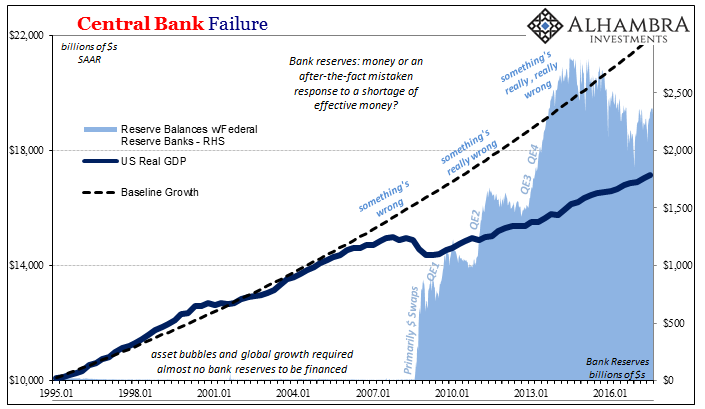

In mainstream monetary convention, bank reserves are at the center of the monetary pyramid. They are the byproduct of any central bank policy which requires direct action. In the US system, they had been absent, however, until around 2008. The reason was the Federal Reserve’s belief that it didn’t require any change in the corresponding balance of aggregate reserves to affect the main lever of pre-crisis monetary policy – the raising or lowering of the federal funds rate.

The market did it for them, which they mistook for uniform belief in central bank monetary supremacy; the theoretical threat of bank reserves, if you like. In other systems, the level of bank reserves was taken as a level or even measure of central bank-driven money supply.

What happened instead was something far different and stranger. The eurodollar system evolved its own set of reserves outside of the accepted concept.

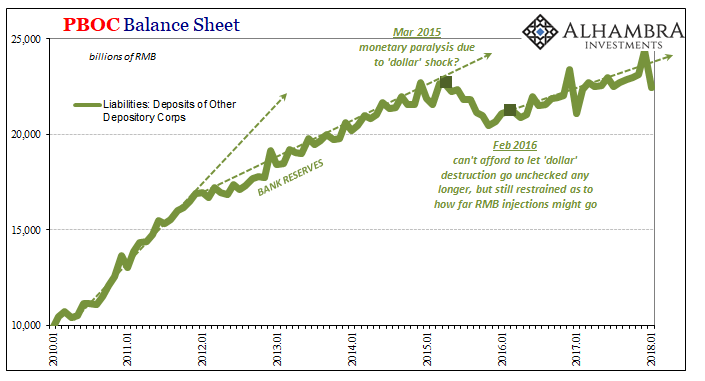

That has had the effect of distorting a whole bunch of other facets of the global economic system. In China, for example, bank reserves still play the monetary role theorized for the US system. They are an important, vital even, piece of the monetary base.

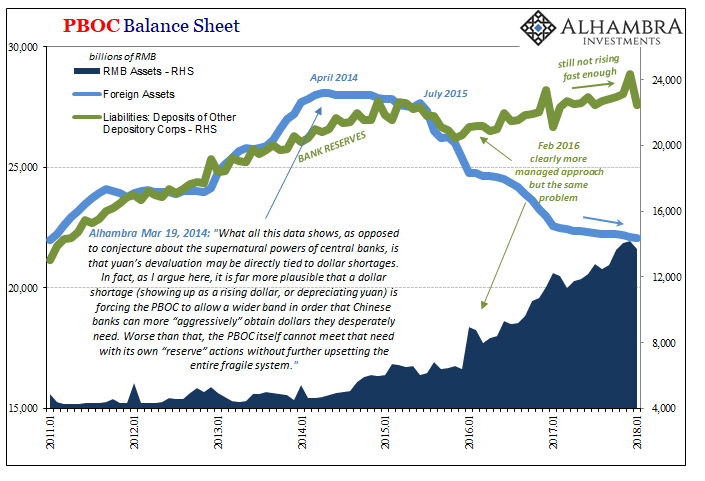

But still unlike the textbook version, China’s central bank does not have full control over them. Though they form the monetary basis for the vast Chinese banking system, the PBOC’s asset side of its balance sheet is literally foreign; as in foreign reserves.

On the surface, that seems more of an accounting detail than any concern for monetary policy. After all, these are assets owned and controlled by the PBOC. To claim that the forex basis for China’s monetary system is ultimately an exogenous factor directly contradicts established doctrine.

This is the primary issue of the eurodollar system, and the true privilege of it being dollar denominated. When we speak of what it means to have a dollar-based world, typically most commentary on the issue revolves around commodity prices, especially oil. The so-called petrodollar looms large simply because nobody seems to appreciate it as merely a subset of the wider issue.

Thus, China attempting to address the petrodollar with an alternate or even competing petroyuan is also misunderstood to a significant degree. Pricing commodities in a particular denomination isn’t nothing, but it’s attacking a symptom rather than the cause.

Trade gets done in dollars. To the extent that oil is priced in them, that is merely a reflection of the eurodollar’s supplanting of gold exchange after Bretton Woods. The primary problem with that former global monetary arrangement was that its designers (including John Maynard Keynes and Harry Dexter White) never formulated any way for global liquidity to expand, or contract, for given needs and requirements.

One reason they didn’t was that global money was itself a foreign concept; individual economies were treated as individual, closed systems. There would be no need for a global currency as any imbalances were theoretically as well as in practice met with flows from one system to another. To place an entire currency regime in between, and thus acting as a global monetary system all its own, was never contemplated as even being possible.

Yet, that’s exactly what happened – and precisely where Economists have lagged behind the real world. The eurodollar transformed into a global monetary system starting in the fifties even if central banks stuffed with Economists still act as if Keynes and White provide them with a solid basis for monetary evaluation. It’s not 1944 anymore, nor is it 1971.

For China, though that country built up the largest store of “foreign reserves” ever believed possible, that only meant China’s “dollar” requirement was larger than anyone else’s. In the mainstream, forex reserves are treated like insurance against a negative currency reaction (devaluation). In reality, they signal the weakness should this offshore monetary system flow in reverse.

At that point, the central bank has no choice but reduce its reserves not to defend the currency but to supply what the offshore market will not. It’s a matter of flow, not value.

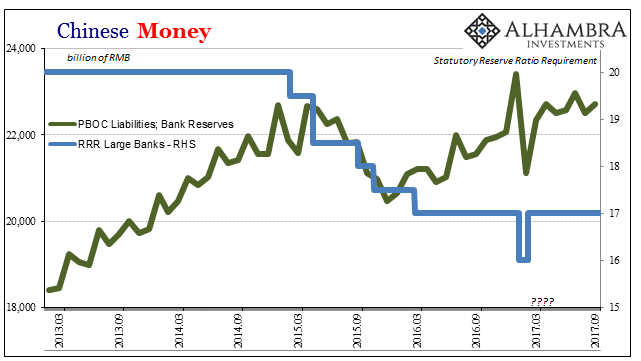

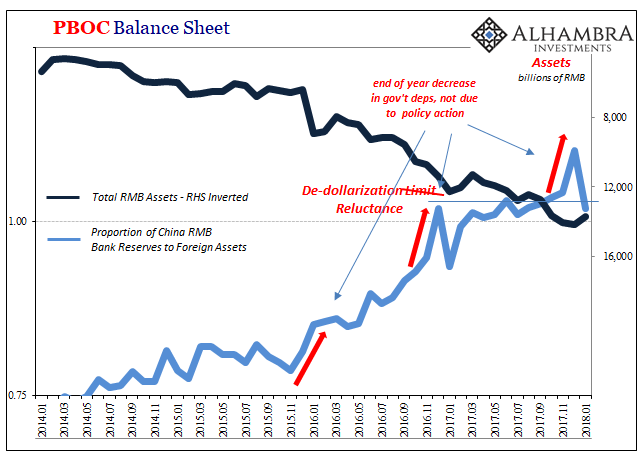

But that can produce drastic downstream effects, too. In lowering the asset side of the PBOC’s balance sheet made up primarily of forex, something has to give. Either the central bank has to allow the liability side to reduce, or it has to step in with RMB assets to fill in the gap in order to keep bank reserves and currency on whatever growth path.

As we have well-documented over the last four years, the PBOC at first chose the former. Starting in April 2014, forex balances were sharply reduced leading in 2015 to an actual and sustained contraction in Chinese bank reserves. To try and offset this grave accounting, monetary officials attempted a market-based response; they reduced benchmark interest rates as well as the level of required reserves intending that the banking system would offset the base money shortfall. It failed spectacularly.

Starting in early 2016, officials shifted toward the latter option (RMB offset). The forex problem remained, so what really changed was how it was treated internally. In order to restore bank reserve and therefore monetary growth, the PBOC initiated a massive “money printing” regime in RMB. They attempted to control any ill-effects by targeting that growth through windows like the MLF into the largest state-owned banks (believing that the Big 4 in particular would behave more responsibly with the funding).

Though bank reserve growth was restored, that didn’t work, either, though the mainstream media particularly in the West has steadfastly characterized the Chinese economy as “strong” and “robust” anyway. Chinese officials know better, and don’t have the luxury of standing on hollow adjectives.

They shifted yet again in 2017 to what can only be characterized as a gamble. Using Hong Kong as a redistribution point, and greatly destabilizing that system in the process, they have attempted to address China’s external dollar problem in a very different way. The advantage of doing so, if it worked, would be to reduce China’s perceived risk factors in order that private eurodollar flow would be restarted in response.

It hasn’t yet happened, though. The PBOC’s forex assets continued to decline even in January 2018 despite more than half a year of CNY’s sharp appreciation (thanks to HK). It leaves China’s central bank with essentially the same choice as they have faced for years; either allow the forex constraint to further constrain bank reserve growth, or throw everything in on an RMB expansion.

It is in this context that any possible petroyuan falls short of its often hyperbolic descriptions. It isn’t ever going to erase China’s dollar issues. At most, and what is the rational and real intent on their part, it helps to ease a small amount of the Chinese “dollar” short. In this situation, ever little bit helps. It’s the “little” part that gets lost in translation.

The PBOC’s RMB restraint shows us that there are far bigger factors to consider, at the forefront being this dynamic between global money and Chinese bank reserves.

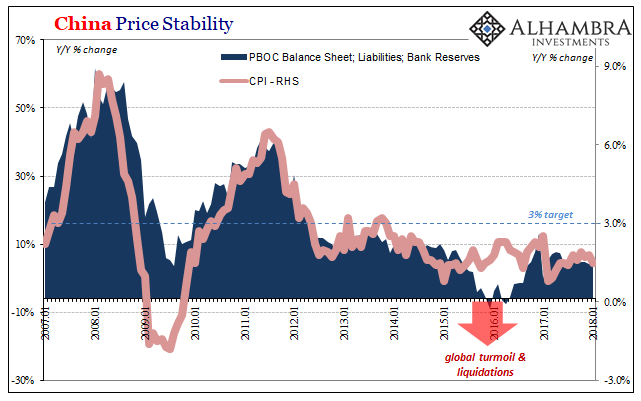

As noted earlier this month, consumer prices in China had broken for the first time with producer prices. Going all the way back to 2012, the Chinese CPI has been left in this clear parallel undershoot (along with other central banks around the world). This divergence tells us that Chinese businesses haven’t been able to pass along input cost increases to consumers, as a matter of economics.

Milton Friedman showed that inflation is a monetary phenomenon, which in this context means bank reserves first and foremost, and therefore conditions originating from the outside of the Chinese system.

What happened starting in 2011 that would have so altered the growth level of China’s bank reserves? That’s an easy question to answer given what we know of eurodollars especially in its role of providing global money supply. The dollar system constrained bank reserve growth in China long before the “rising dollar” amplified the problem.

And, as you can plainly see above, when the level of bank reserves was allowed to contract in 2015 it didn’t pull down Chinese consumer prices (very likely because that private banking offset in reduced reserve requirements provided some substantial cushion) but did coincide with global liquidations in financial assets.

That leaves us with two conclusions. First, global money through the eurodollar system is the monetary baseline for what are still thought of as independent and closed systems. Money growth therefore is an exogenous factor in this way from the perspective of the PBOC (and other central banks). That matters because, again, even in January 2018 China’s forex assets are still falling, though at a much lower rate than over the prior few years. It also means that central banks are themselves constrained in their policy choices as well as how they might carry them out.

Second, bank reserve growth is decelerating again. Given the policy alternatives, the PBOC has apparently chosen to let that happen instead of going even further with its RMB offsets. Why? It’s not yet near 2015 levels, but the tightening starting coincidentally in June 2017 is noticeable (the same month where CNY appreciation really took off). It certainly adds intrigue to what just happened globally in late January/early February.

The dollar matters more than simply which commodity is priced in what currency. There are logistical and infrastructure matters, the considerations for plumbing, that to the otherwise unfamiliar appear to lead central banks toward confusing propositions.

The PBOC can print money, but doesn’t. China’s central bank has been restricted in bank reserves for years. In theory, central banks are central; in reality, they are reactionary and peripheral. This explains a lot about the last eleven years, China providing yet another example in practice. Petroyuan isn’t an answer to that problem, its one minor way to attempt to treat the symptoms of the greater disease, a malady that is still progressing in strange and risky ways.

In other words, replacing the eurodollar is a Herculean task. The Chinese surely wish “we” had started in 2008. Western officials, many now gripped by inflation and boom hysteria, still don’t know it’s a problem let alone its extent and depth.

Stay In Touch