Last week, Bank of Japan Governor Haruhiko Kuroda unleashed a mini-controversy with remarks he now claims were taken somewhat out of context. On March 2, speaking before Japan’s parliament, the central banker sure sounded quite confident:

Right now, the members of the policy board and I think that prices will move to reach 2 percent in around fiscal 2019. So it’s logical that we would be thinking about and debating exit at that time too.

In this age of inflation and boom hysteria, it’s understandable that this statement would be shopped worldwide as proof of it. The yen surged to a new high, which was further seized upon as markets behaving like this was all real.

Today, Kuroda has been appropriately admonished, or at least it appears that way. Walking back his comments, BoJ’s leader now says, “Right now it’s too early to debate what tools we should use, and what kind of pace we should take.” He further “clarified” that his fellow policymakers are only thinking about what might happen if their view proved to be the correct one.

That’s the real question; what are the chances of that?

Stepping back from what he said, as well as the absurdity surrounding it, Haruhiko Kuroda has been saying April 2019 as a potential target for exit for years. This really isn’t anything new. Nor is the timing particularly important. It is more political than economic condition (another “data dependent” central bank).

BoJ Governors rarely serve more than one five-year term. Kuroda’s expires this April, his first month on the job bringing with him the April 2013 grand QQE experiment. There are all sorts of rumors that despite his advanced age, 73, he will be retained to see out his 2% target in a bid toward policy stability.

Since that isn’t going to happen anytime soon, the projection for it remains just over the horizon as it always has been. Remember, Kuroda’s first inflation projection was that it would take two years for 2% to be reached. The BoJ even raised its definition of price stability from 1% concurrently. It was expected this would be reached by April 2015.

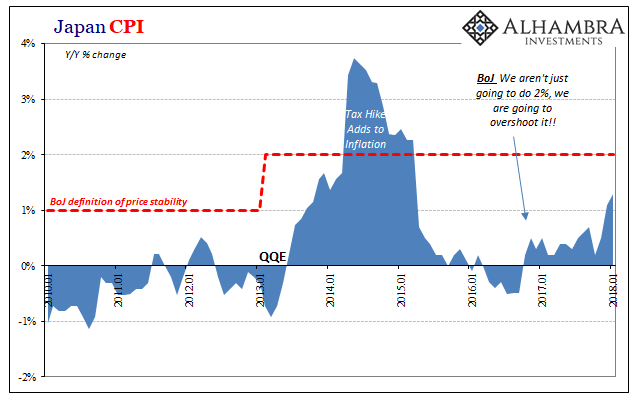

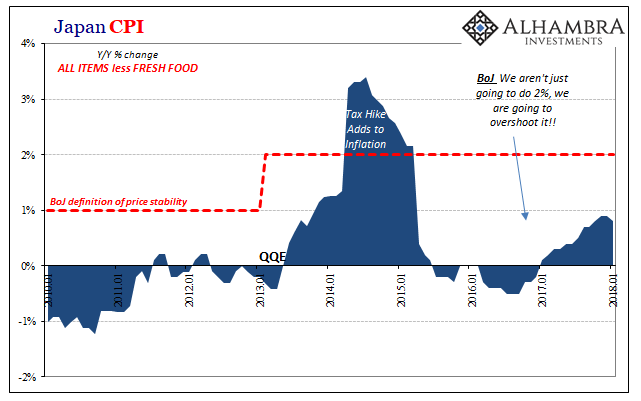

After just about five years now, did QQE work? Inflation is the target from which that question was supposed to be answered. Japanese consumer prices are rising, but aren’t yet close to the target let alone staying there in sustained fashion.

Further, Japan’s economy is talked about as if having achieved an unprecedented boom; at least for the last thirty years. This is why, more than anything, Kuroda is hanging on in his job. Japanese officials want for it to be real, and they are being real careful so as not to upset what they are thinking is a possible if fragile pathway toward success.

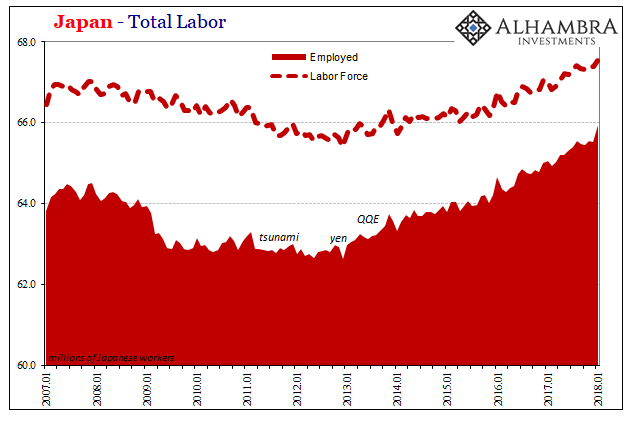

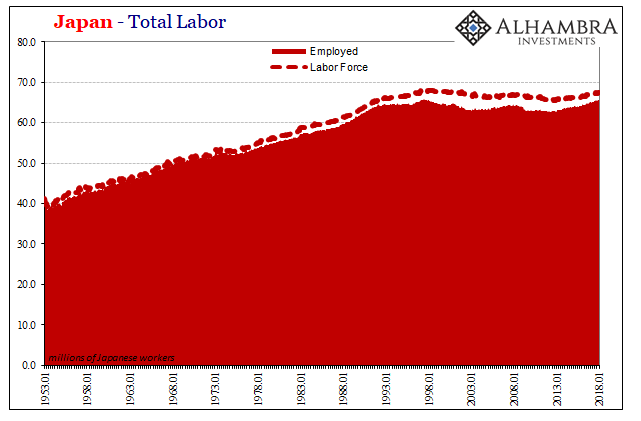

On the surface, it does appear as if all the monetary experimentation achieved some substantial positive results. The unemployment rate in Japan was about 4.3% at the start of QQE, most recently in January 2018 falling to 2.4%. It’s another country having reached the academic definition for full employment and therefore, economists expect, the inarguable region set up for wage-driven inflation.

As we have learned in the United States and elsewhere, however, depending upon the unemployment rate is a tricky business, at best. For one, it had been falling over there since Japan’s brush with the Great “Recession” in 2009. But even what you see on the chart immediately above is misleading. Employment is actually growing, to be sure, as it is in the US, and the labor force with it. This cannot be the end of the evaluation, though.

That’s always the case whenever analyzing the various “pump priming” schemes of modern Economics. The concept in theory is simple; some form of “stimulus” is added in order to create activity for the sake of activity. The idea is that the rest of the economy is emboldened by even the most wasteful of processes (Keynes’ pyramids in the desert) which has the effect of driving first “animal spirits” and then actual production. Full recovery easily follows.

Pump priming is not so straightforward and often amounts to some kind of redistribution. You take from one part of the economy in order to get another part moving forward with the intent that the forward progress in that other is enough to get the whole thing restarted again and thus everyone is better off for it – including those who were at the start on the wrong end of redistribution.

The pivot in Japan was yen; it’s often the currency. Driving down the currency exchange for an export-oriented economy was thought to be the path of least resistance for this new Abenomics (which wasn’t really new, even for Japan). As is typical, they achieved Step 1.

Obviously, given that the inflation target still hasn’t been reached, the results of yen-driven redistribution cannot have been straightforward despite the unemployment rate.

This was because first and foremost the “stimulus” placed Japan’s workers on the wrong end from the very start. A falling yen should have been a boost to corporate profits, particularly those firms in the export sector which then would have been shared with workers later on. Instead, the Japanese government has had to constantly cajole Japan Inc. into bonuses, the rare wage increase, and most of all to stop moving production capacity overseas (particularly into China).

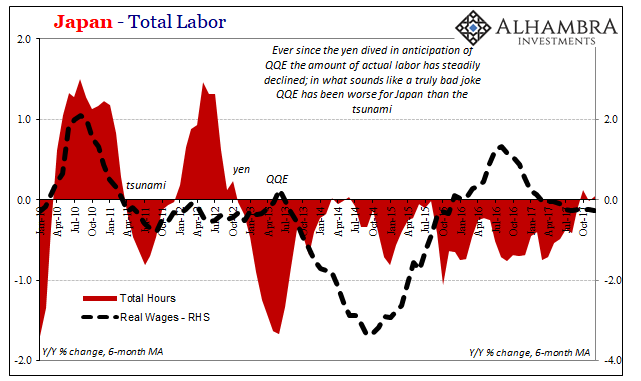

The net effect, from the worker perspective, was that more Japanese people were working at the margins but doing less overall. Fewer total hours have been worked, and wage rates have precipitously declined. In other words, the pump priming combination of yen and QQE didn’t devalue the currency so much as Japanese labor.

As a result, the unemployment rate doesn’t tell us all that much about Japan’s economic condition. It instead indicates only part of what happened, where Japanese businesses found it cheaper at the margins to hire new workers at lower rates than to use existing workers at existing wages. The deflationary pressures simply shifted to the most vulnerable of Japan’s stakeholders.

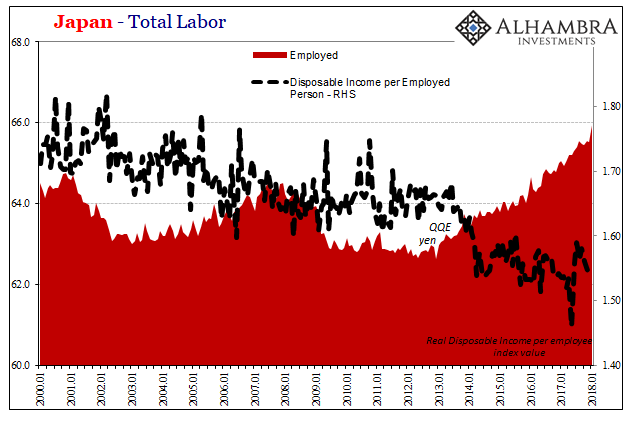

We see these lamentable results in Household Accounts. Disposable Income aggregates especially in real terms have collapsed. As you can see above, income per worker has fallen as a consequence of more workers working but doing less and making less.

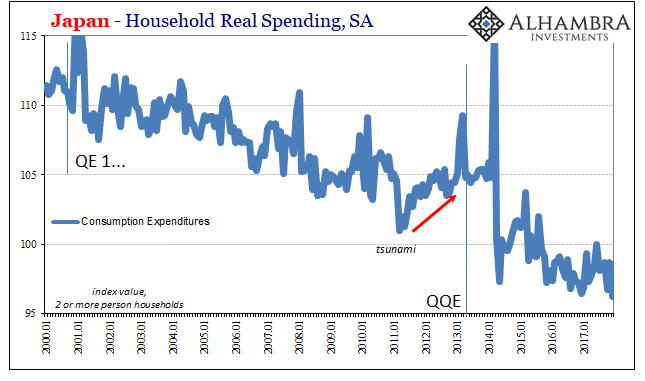

Therefore, quite predictably, Household Spending has collapsed post-QQE.

The 2014 tax increase in particular was devasting for Households. Spending had been falling for years as a consequence of now several lost economic decades. But what happened in 2014 and after was a wholly unnecessary intrusion into what since the 2011 tsunami had looked to be almost organic progress.

Even accounting for Japan’s near-suicidal demographics, none of these accounts can be confused for progress; especially in the period following QQE.

It’s not quite the picture painted by an upbeat central banker speaking confidently about ending a redistribution program the mainstream desperately wants to sell as a clear technocratic success. The Japanese people remain on the losing end of all this, still, now five years into a nakedly absurd experiment.

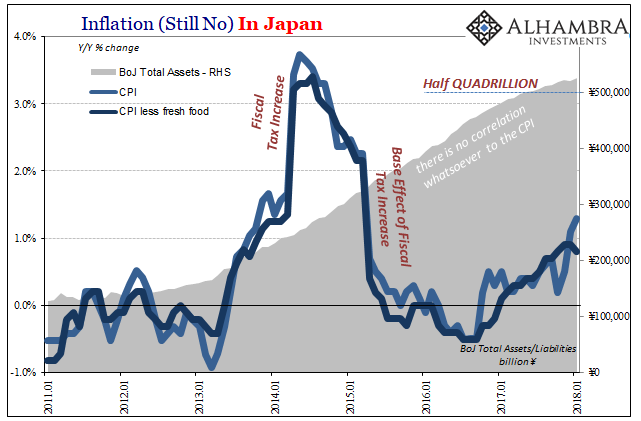

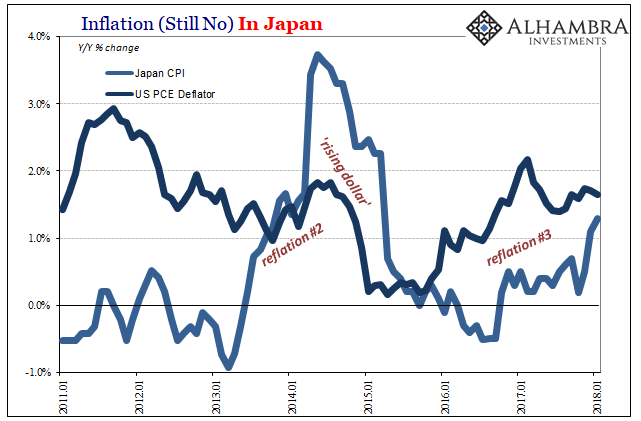

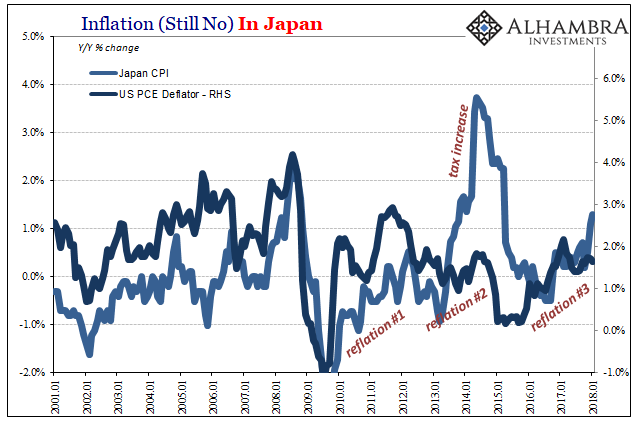

And the bump in inflation for Japan’s CPI cannot be attributed to it, either. There is no correlation whatsoever between consumer prices and BoJ’s utterly ridiculous half a quadrillion sized balance sheet.

Rather, the CPI in Japan behaves in closer correlation with other inflation indices around the rest of the world; including US versions of consumer price estimates. Japan, like the rest of the world, is caught up in reflation #3 of the same eurodollar decay ongoing since August 2007. The parallels are much easier to see on a longer time scale.

Not only has QQE failed in its primary purpose, it has further devastated the Japanese workforce all for the sake of partial statistical manipulation. By the unemployment rate alone, everything in Japan appears to be good if not fantastic. At 2.4%, how can there not be inflation by next year?

The answer to that question is quite simple; you can’t hope to move forward by devastating your workforce (an acknowledgement that applies universally). No recovery is going to come from the purposeful intrusion of such negative factors. Call it pump priming if you wish, but in truth it’s been terribly effective redistribution. More workers who in the aggregate work less and receive lower pay equals recovery? Not even close.

That’s why it’s March 2018 and we are still talking about it on uncertain terms for April 2019, having long ago surpassed the first scheduled completion of April 2015. Half a quadrillion already in the books, and really no end in sight. QQE didn’t work unless your goal is further economic ruin. As elsewhere in the world, the unemployment rate is nothing but the modern effect of the money illusion. And it’s not even money.

Stay In Touch