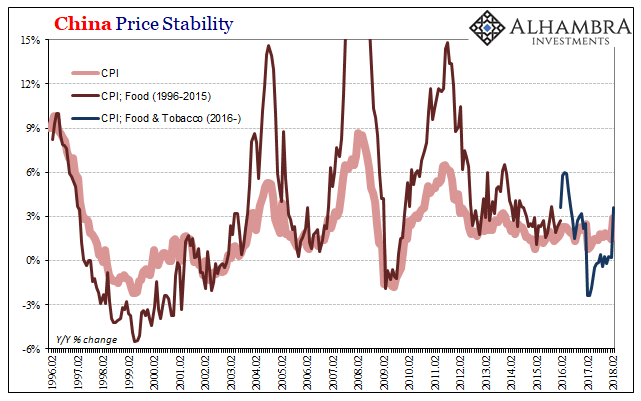

By far, the easiest to answer for today’s inflation/boom trifecta is China’s CPI. At 2.9% in February 2018, that’s the closest it has come to the government’s definition of price stability (3%) since October 2013. That, in the mainstream, demands the description “hot” if not “sizzling” even though it still undershoots.

The primary reason behind the seeming acceleration was a more intense move in food prices. Rising 3.6% year-over-year, China’s index for consumer prices of food and tobacco had gained just 0.2% in January on an annual basis. Such a big monthly change is exactly what the inflationary scenario is looking for.

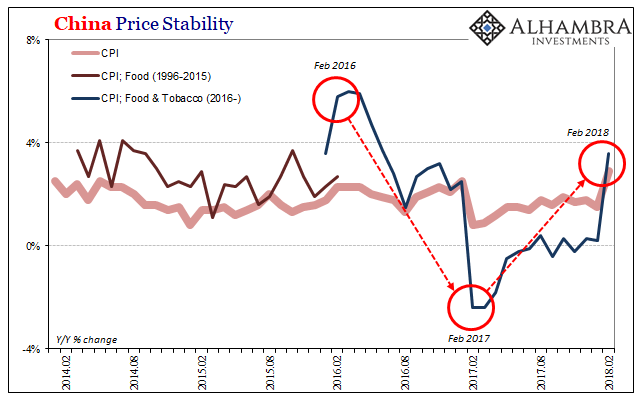

Except that this one happens to be nothing more than a February problem. In this case, unlike other Chinese accounts, it has nothing to do with the calendar placement of the Golden Week. Instead, over the past two years these are strictly base effects, the statistical artifacts of 2015’s porcine herd devastation.

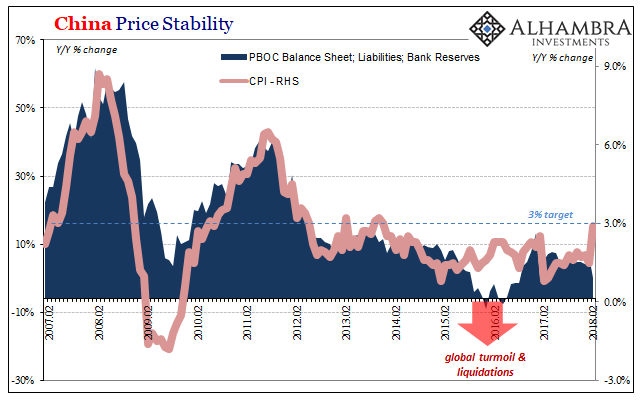

The PBOC hasn’t yet released its balance sheet figures for February, but we don’t need them to validate China’s CPI as monthly noise. There is absolutely no way bank reserves spiked last month in a manner consistent with this apparent change in yearly consumer prices – just as there wasn’t last February a rapid deceleration in bank reserves coincident to the first round of base effects that compared then to February 2016 depressing both price indices.

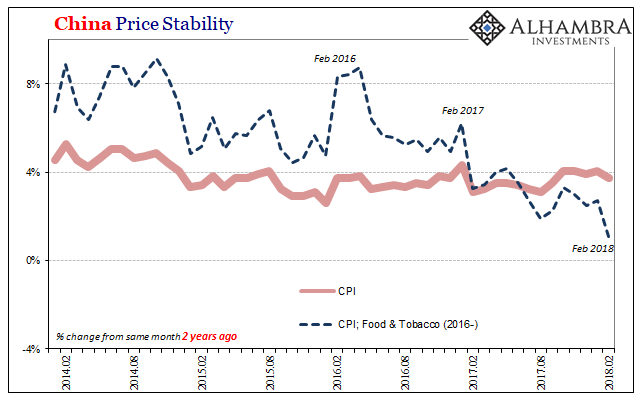

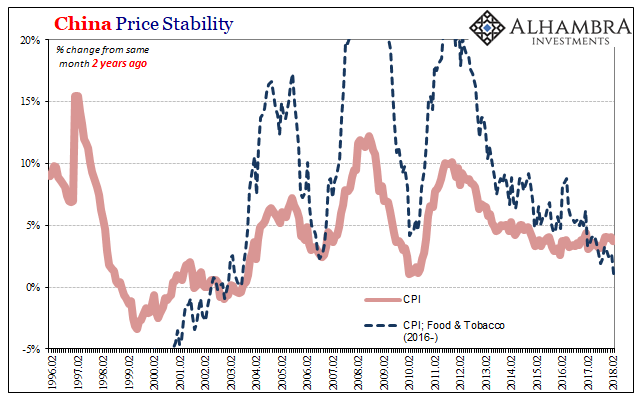

One easy way to check for these assumptions is by calculating price changes over a two- rather than one-year period. What we find is that Chinese consumer prices are largely stable below the government’s mandate, in good part because the increase in food prices has been in general slowing down since 2011 – which is when the eurodollar system permanently broke and China’s economy last performed like it had in the precrisis “miracle” years.

Consumer price boom? No. Statistical base effects creating an outlier, and an obvious one at that.

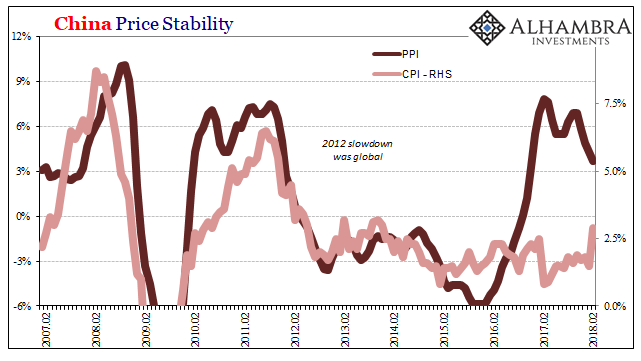

The more interesting development may be instead in China’s PPI. Producer prices surged over the past year and a half without triggering any direct response in consumer prices. This divergence is something new, not recorded before in modern, industrial China’s inflation history.

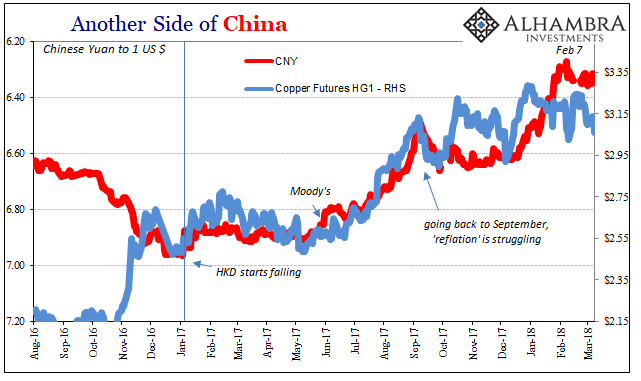

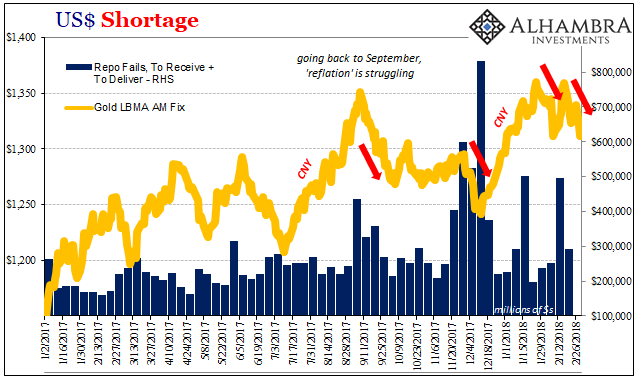

If producer prices continue to decelerate, that will leave bare any reason to expect consumer prices will behave, too. That’s because falling producer prices might propose a re-evaluation particularly in commodity markets of this whole reflation, globally synchronized boom idea from the start. After all, that’s why many commodities had rocketed off the February 2016 bottom, in anticipation of a complete turn in global growth, especially inside China. The lack of follow through into consumer prices, businesses being unable to pass along that first wave of input cost increases, was always a bad sign for these economic reasons.

Stay In Touch