According to one research company, new Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell was disgusted and angry at his press conference yesterday. The firm, Prattle, employed facial recognition software to track Powell’s expressions throughout his inaugural press conference. By their count, he was disgusted 36 times, angry 41 times, and expressed contempt another five. Powell conveyed joy on a mere four instances.

These labels are surely overstating the degree to which Powell showed any emotion. His emerging talent, if it may be called that, is more Greenspan-like (not a compliment). He will say a lot without saying much. For the maestro, at least, that was by design. For Powell, I’m starting to believe that’s all there is.

These apparent negative emotional expressions correlated mostly with questions about inflation. No surprise there, nobody at the Fed has any answers and haven’t for years now. Whether it has been oil prices or Verizon’s unlimited data plans, there’s always something in the way of meeting the central bank’s explicit inflation target – the joint legacy project of both Ben Bernanke and Janet Yellen (one of the more legitimately interesting parts of their joint appearance at Brookings recently was both discussing their recollection of 1990’s arguments on explicit targeting and Alan Greenspan’s objections to it).

But if Powell is angry about being unable to answer for six years of undershooting inflation, of the few times he was happy it was in talking about the current state of the economy. According to this key policymaker, things are really going well. Really well.

It’s true that rates are the higher they’ve been for 10 years, but also the economy is the healthiest it’s been for 10 years, since before the financial crisis, so it’s a healthier economy than it’s been for 10 years.

Prattle scored that comment under “joy.”

This is Powell’s biggest fault, a mistake Greenspan would never make. By what standard is he claiming this? There is only one that fits the definition, and that’s the unemployment rate which is causing all this disgust and anger about inflation.

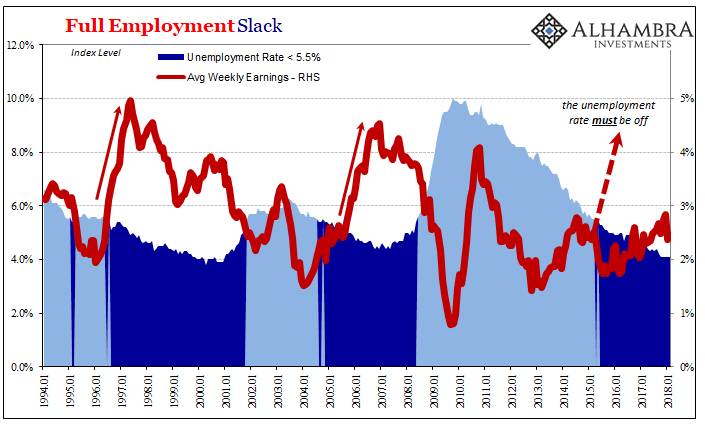

The unemployment rate is low by any standard, that’s not at issue. The question is whether or not it’s legitimate, or if it’s being obstructed by economic artifacts it was never designed to measure. We don’t know for sure, and won’t until the meeting transcripts are released five years from now, but there appears to be considerable disagreement on this crucial point (leaving, as noted yesterday, the direction of the dollar to describe joy or disgust from the Fed’s models).

Some Economists have argued there are structural factors to blame outside the scope of monetary policy and therefore the unemployment rate is an accurate depiction of the labor market. But if that was so, where’s the wage acceleration and consumer price increases that are supposed to follow from them?

On the other side is, to be frank, common sense. Several years have passed waiting for this to take shape. If it was a heavyweight boxing match the referee would have long ago thrown in the towel.

Powell, it appears, doesn’t hold to the reservations publicly expressed by his immediate predecessor. Last September, surely realizing her time was nearly up and wishing to go on record for once with something tangibly defensible, Janet Yellen said:

My colleagues and I may have misjudged the strength of the labor market, the degree to which longer-run inflation expectations are consistent with our inflation objective, or even the fundamental forces driving inflation.

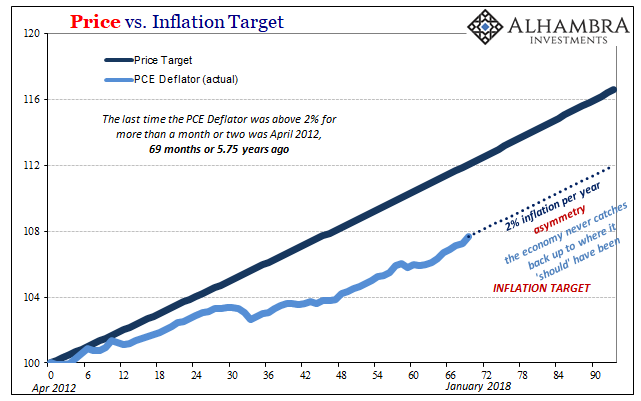

One of the ways in which to think about the topic is not strictly inflation, or the yearly change in consumer prices. There is a good deal of talk and discussion about symmetry, or symmetric policy. I’ve referred to it on several occasions, much of which is actually positive in that it reflects the counterargument to Powell’s blatant optimism bias.

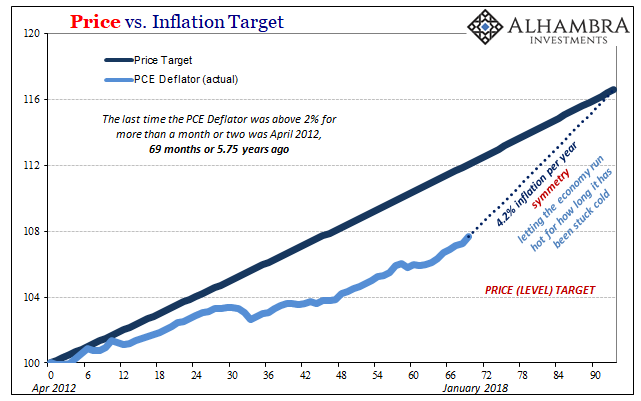

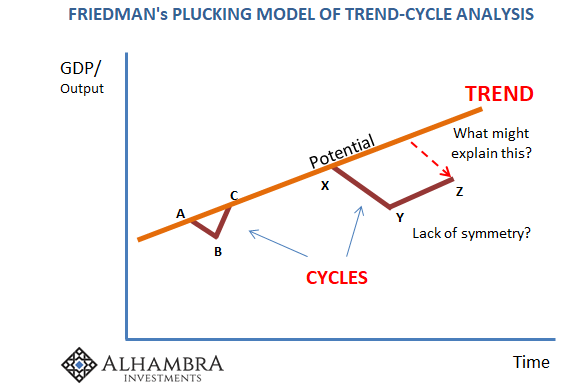

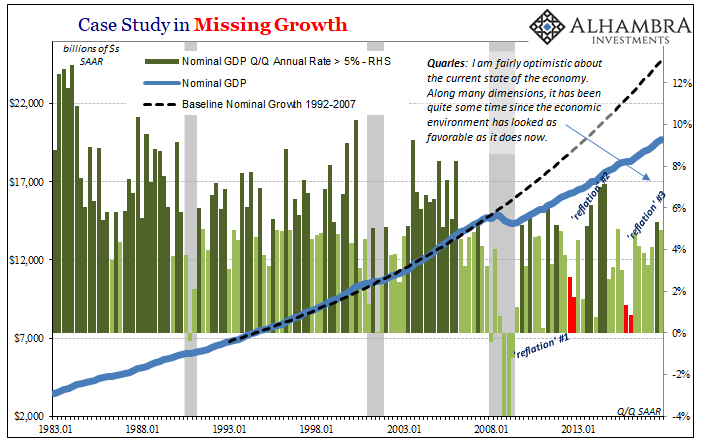

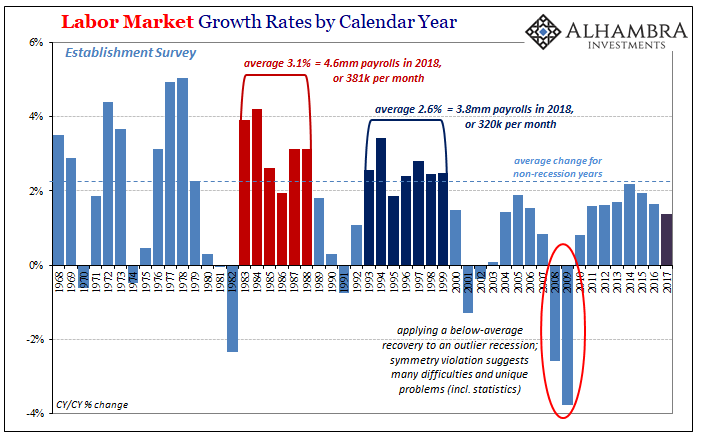

Symmetry in inflation recognizes something like mean reversion; if something is weak for a prolonged period, to get back to trend or average it must be unusually strong for an equal period. That is what recovery is after all, a period of above-average growth following any recession so that at the very end of the business cycle the economy is back on the same trendline as from before it.

Six years of undershooting inflation, dating all the way back to April 2012, means the Fed is far, far behind in its self-appointed mandate (there are separate arguments to be had about whether a 2% PCE Deflator is anyone’s useful definition of price stability). To get back toward the good side, symmetry argues for letting inflation get hotter than 2% for a prolonged period.

Powell’s non-answer yesterday:

Our inflation objective is symmetric in the sense that we are trying to prevent persistent deviations from 2 percent in either direction.

Persistent as in 6 years?

The basis for any above-target condition would presumably be rapid and accelerating economic growth (the unlocking of monetary effects that are likewise presumed to be held back by “transitory” factors). That is the real issue here, even if policymakers like Janet Yellen were falling backwards into it.

The economy experienced a sharp decline in 2008-09, but rather than symmetry holding at that point, the recovery was further less than trend even after. It was, in essence, this double shock that plagues us today. This isn’t supposed to happen, leading to all kinds of preposterous theories about why it did (drug addicts and Baby Boomers).

Therefore, for Powell to be correct about his assessment, symmetry must somewhere be involved. But it’s not. Even the updated projections from the FOMC published yesterday concurrent to his angry and disgusted press conference aren’t anything like symmetry.

Nor are there other indications from outside the Fed that has changed, or is about to, either.

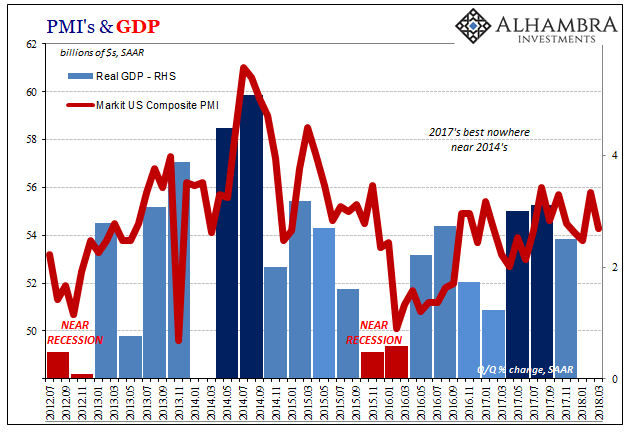

Markit released its composite Purchasing Manager’s Index (PMI) today, the combination of its PMI’s for manufacturing and the services economy. It’s not perfect by any stretch, but its record over the past five years during the slowdown has been much better than most. For March 2018, the flash estimate was only 54.3.

Both Markit as well as GDP continue to show that there hasn’t been any acceleration whatsoever. Compared to the upturn in 2014, both indications have it far, far short of even that low bar. What in the hell is Powell talking about the best in ten years? The most charitable description is that it’s the best in two years, which is no appropriate standard for evaluation.

Not only does last year’s growth, if it continues this year and doesn’t get worse, fall far short of 2014 it does nothing to make up for the near-recession in between – the same symmetry violation that has repeated now three times going back to the original decline during the Great “Recession.” I suggested earlier this week this whole period should be called the Great L, but in truth it’s been three completed “L’s” so far – with China unfortunately joining in on the last one.

In short, asymmetry even during this upturn is still working against us – which is why, I believe, contrary to the picture of the economy provided by the unemployment rate the labor market was shockingly weak last year.

In policy terms, the issue is moot anyway. There’s nothing the Fed can do about it, if it wished to tackle this gross deficiency. It already tried and now judges its efforts a qualified success. Four QE’s and years of ZIRP couldn’t discovery symmetry, so what can it do that would should Powell ever wake from his fairy tale?

The only benefit of this type of discussion is disgust and anger. Monetary officials should be made uncomfortable by all this, even if it’s only over inflation for now, and the public should notice that discomfort coming as it does from their inability to provide minimally plausible explanations. It’s a very small silver lining, but further discredit could lead eventually in the right direction. If we have that much time.

Stay In Touch