Why isn’t Ford’s news getting a bigger reaction? This was no small announcement, essentially a retooling of its entire business. The company will, in effect, no longer build and sell cars; at least not cars as we think of them. The Mustang, it appears, will be the lone survivor among that category, but the Taurus and even the Focus are going to disappear.

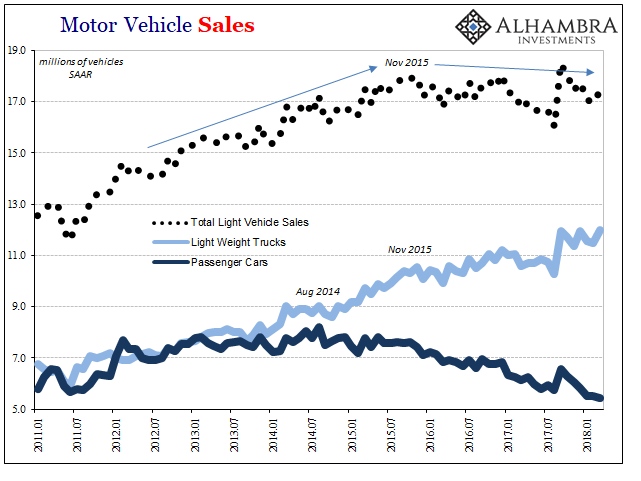

The proximate cause is obvious enough. Car sales have completely and totally collapsed. In August 2014, the Commerce Department figures about 8.2 million (that’s a seasonally-adjusted annual rate, not the actual number of units) of them were sold. As of the latest data for March 2018, it was a pathetic 5.4 million. It’s an astounding 34% drop. The last time automakers sold so few cars was at the depths of the Great “Recession.”

The auto business is not gripped by total collapse, however. Offsetting the car segment has been better results in higher margin light trucks including SUV’s and crossovers – both of which Ford will focus upon. The timing of the shift does suggest oil and therefore gasoline prices are responsible, at least partly. That same timing, August 2014, might also suggest the weaker macro environment that developed shortly thereafter.

We also have to consider that it probably wasn’t just coincidence that light truck sales slowed starting after November 2015 (downturn accelerates) as the dropoff in car sales accelerated. The net result of both was total vehicle sales that have since plateaued and even dropped at times. It’s been this way for now two and a half years. It should be getting better as is oftentimes claimed.

If it was indeed the economy that has been to blame, then this seems a pretty big negative statement on future expectations:

The No. 2 U.S. automaker said it now plans to cut $25.5 billion in costs by 2022, up from $14 billion in cuts it announced last fall.

Ford Chief Executive Jim Hackett told investors the company is undergoing “a profound refocus” of its operations and may exit unprofitable businesses.

For now, this is being characterized as nothing more than “consumer preferences” because it doesn’t fit the narrative. This isn’t the reaction of a company fully confident in an economic turnaround.

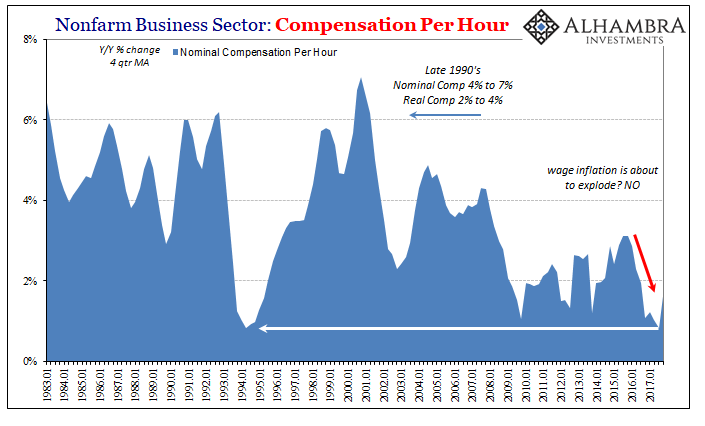

Nor is one consistent with the debate circulating through the Ivory Towers of the Federal Reserve. They are increasingly talking about “overheating” again, as if they learned nothing from the last time they did so – 2014. Then, as now, they were, to put it mildly, premature in their optimism.

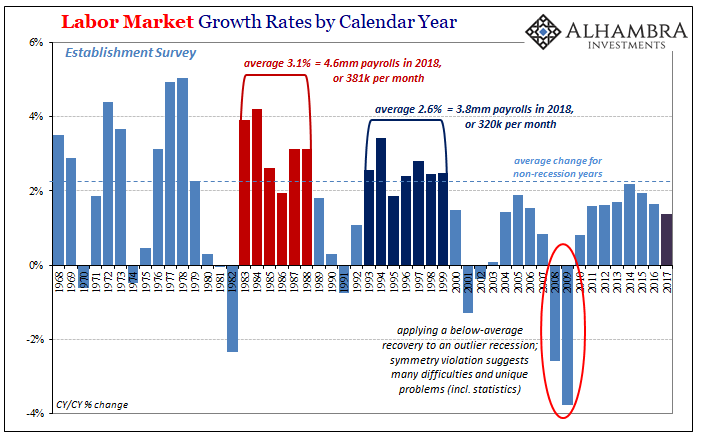

It should not have been a surprise given the unemployment rate’s sharp drop. Counterintuitively, the decline didn’t suggest a return to health and recovery as it might have in the past, it instead signaled a lot that was wrong. People on the ground knew what was missing that the statisticians at the Fed couldn’t fathom for their regressions (predicated on assumptions about the past).

We are repeating the same things over and over, as the New York Times notes just today:

“I don’t see evidence of the wages getting higher, except for specific types of jobs, like management, banking,” she said. “My attorney friends aren’t hurting.”

Yet Federal Reserve officials are beginning to worry about a possibility that seems remote to workers who still feel left behind: the danger of the economy’s running too hot, destabilizing financial markets and setting off a rapid escalation in wages and prices that could force the central bank to slam the brakes on growth.

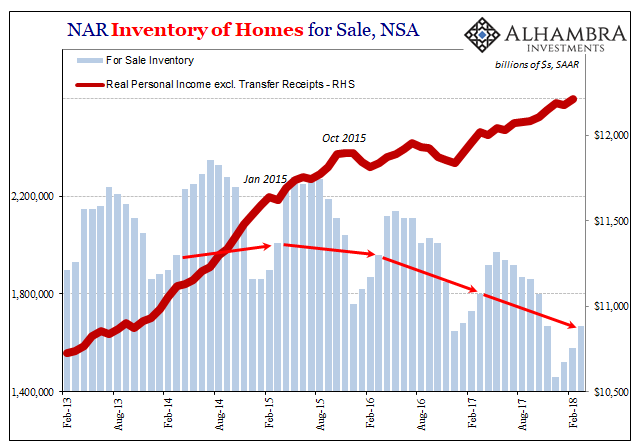

In adding another $11 billion in cost cuts to its plans, which way might Ford see it? The same way, I think, as the housing sector. What were once the two pillars of an anemic to non-existent recovery aren’t even that anymore. It’s a big reason why last year’s labor market was among the worst non-recession years in labor market history.

One comment in the article stands out for all the data you see above.

Constance Bevitt, who does freelance work in Montgomery County, Md., said Fed officials were wrong to be worried about overheating.

“When they talk about full employment, that ignores almost all of the people who have dropped out of the economy entirely,” she said. “I think that they are examining the problem with assumptions from a different economic era. And they don’t know how to assess where we are now.”

Unlike before, I wonder if Ford officials might now finally agree. Being an Economist, it seems, has become an impediment to rational analysis and common sense. Maybe car sales are falling so much because they are the products that struggling workers would normally buy – if “overheating” was in any way possible.

Stay In Touch