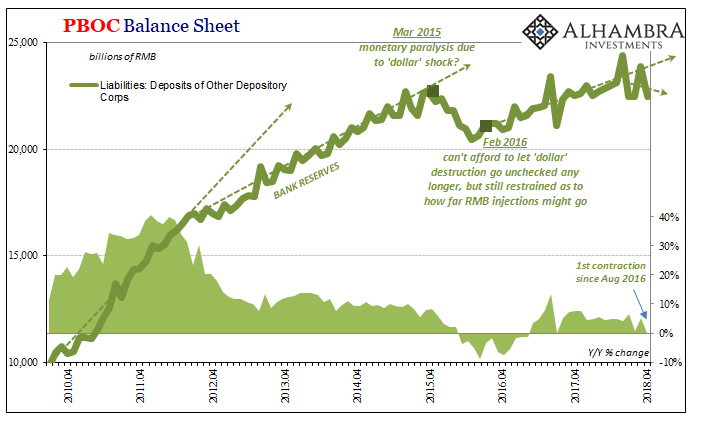

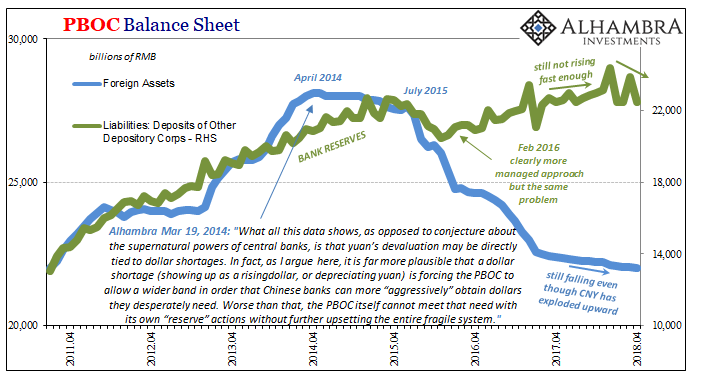

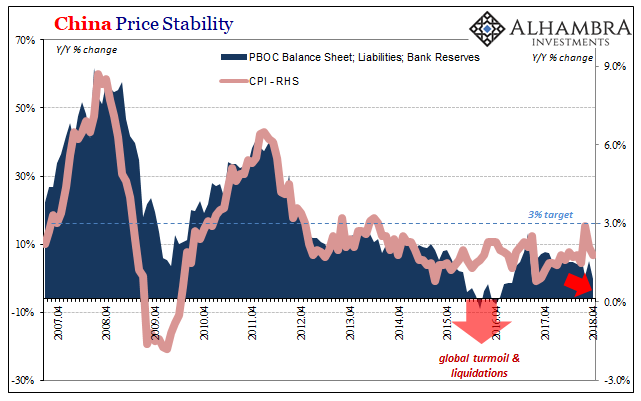

Chinese bank reserves contracted in April 2018 for the first time in almost two years. The decline was small, just 0.2%, but it is still represents a significant deviation from the limited growth since the turmoil in 2015 and early 2016. The decline in reserves further corroborates our theory of events.

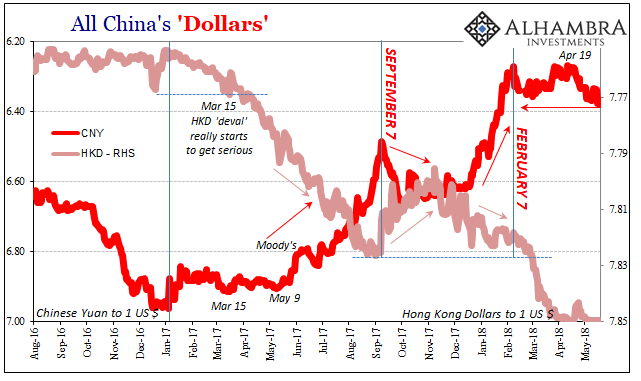

To briefly review, China has a currency problem first and foremost; CNY DOWN = BAD. Chinese officials have tried everything to arrest the issue or have at times attempted to alleviate its worst tendencies. It appears as if they had early last year (after CNY continued falling even as “reflation” gripped almost every other place, especially around the EM world) settled on a stable CNY at all costs.

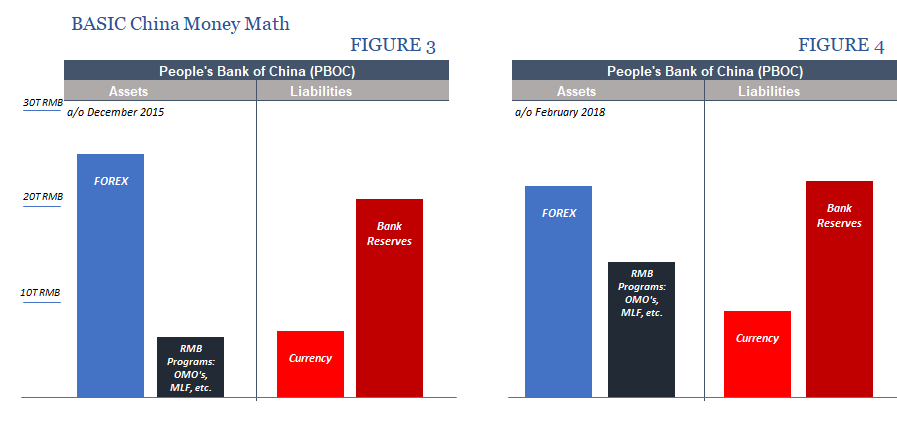

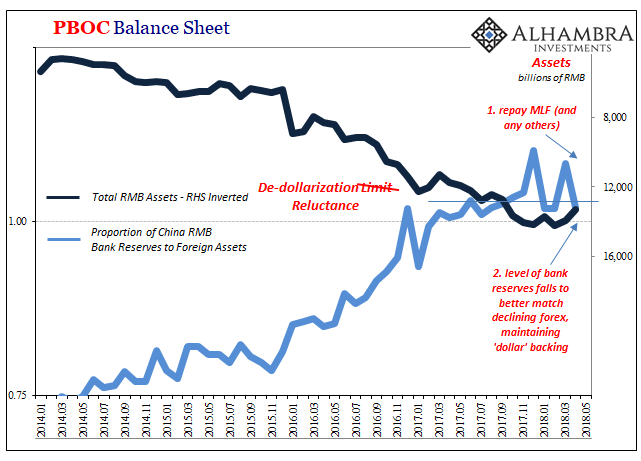

But that would have meant ending the remarkable RMB “printing” the PBOC had undertaken so as to keep its own asset side rising enough to produce positive bank reserve growth. It placed the central bank in quite the conundrum.

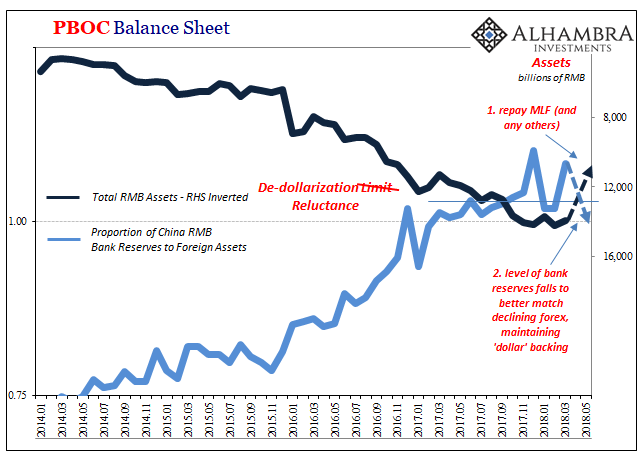

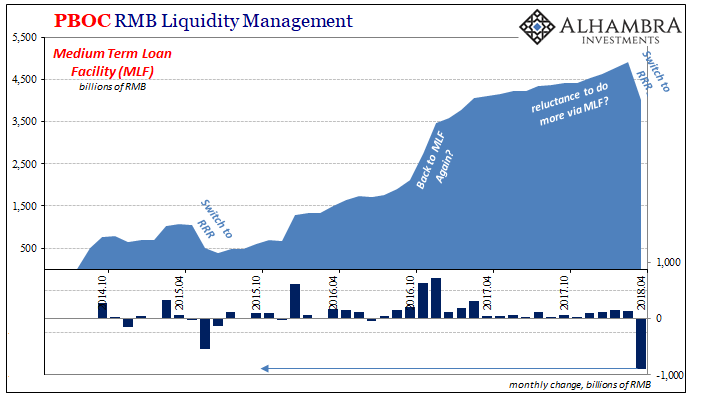

As noted before, not long ago it appeared authorities hit upon a rather novel scheme (though they tried it once before, in 2015, to disastrous effect). They would first require large banks to repay the MLF and other window borrowings. If they did, these depositories would be given a lower RRR. The combination of those two things would, in theory, allow the PBOC to reduce bank reserves while maintaining liquidity; a public to private substitution (though, in this case, a central bank to state-owned bank substitution).

The first part had already been confirmed, meaning that when the MLF balance for April was reported at the beginning of this month it was substantially lower than in March. The total drawdown was more than RMB 900 billion.

All that was left to confirm was any coincident decline in bank reserves taking into account whatever other actions the PBOC might employ. The April balance sheet update does confirm, as noted at the outset, a decline in bank reserves and therefore the contours of a changing policy.

While the mechanics have fallen right in line with our expectations, the implications are far more important. Prioritizing a stable or even rising (where possible) CNY suggests that Chinese officials are not sanguine about global prospects. If they were truly optimistic even a little bit in the same fashion as “globally synchronized growth”, they would need no special emphasis on currency exchange one way or the other; growth itself would take care of stability, just as it had before the dramatic change (for EM’s and China) duruing the first pieces of the “rising dollar” (2013).

Instead, to employ not one but several creative (to put it kindly) arrangements to accomplish currency stability as a target is indicative of what I wrote at the beginning of this inflection in January last year:

If the Chinese are manipulating their currency, it is only because nobody understands the global currency as it actually is (thus, even in which direction the currency might even be “manipulated”). Far be it for me to sound as if a defense of the Communists, my criticism is far more directed at recognizing the actual problem before either (any) side goes off and makes it even worse. This is the historical danger of prolonged periods of monetary instability that always breeds economic malaise and depression; a search for answers that rarely includes any.

That sums up the last year and almost five months. CNY is higher, but what was actually accomplished aside from pressing the calendar forward one year and almost five months? Yuan has reobtained a downward tendency again, Hong Kong is flirting with disaster, and now the PBOC has locked itself back into a policy that not three years ago didn’t come close to producing predictable results. Rather, it was the biggest disaster since 2011.

Stay In Touch