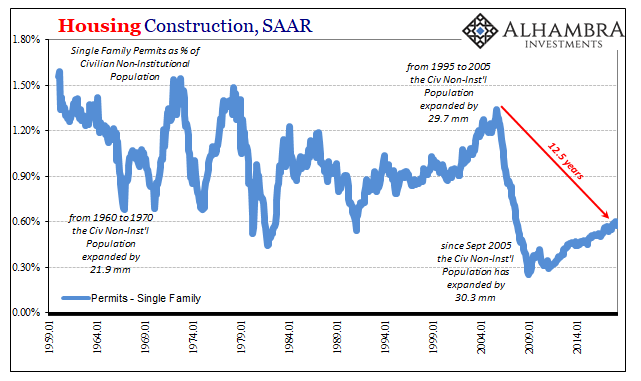

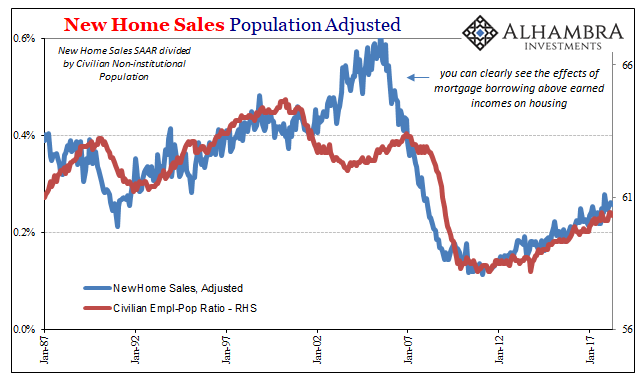

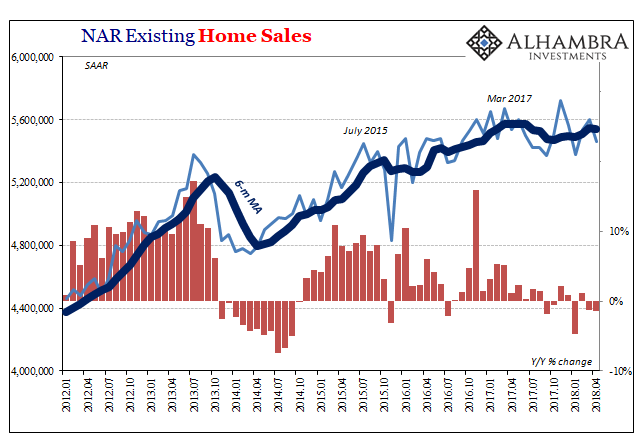

There are three major housing related data series published each and every month. The first is on construction of new units, the intersection of real estate and the macro economy compiled by the Census Bureau. The second is the number of newly built single-family homes that have been sold, relating obviously to the level of construction. These numbers are also complied by the Census Bureau. The last pertains to resales, or the sales of existing homes estimated by the National Association of Realtors (NAR).

Though these are different data sources, when combined they give us a pretty comprehensive picture of the situation in housing. Home construction continues to grow albeit slowly because new home sales do. Both have progressed at historically subdued rates. It doesn’t change year in and year out.

The same is true for resales. At the peak of the last housing bubble in 2005, the NAR figures existing sales reached an annual rate of more than 7 million (SAAR). Over the past year going back to last March, the level of resales has been stuck around 5.6 million.

The NAR reports that April 2018 was another down month for real estate. The housing market cannot seem to gain any traction, which isn’t really surprising given the perspective offered by construction and new home sales. There is activity to be had, but not a whole lot especially in historical context.

That’s not how the real estate market is characterized. We should expect some gloss and even outright spin from the NAR; it is, after all, a trade group that represents realtors and their vested interest in a robust market. But stating it that way requires overstating other macro factors. The result is a simple and sustained contradiction.

NAR’s Chief Economist Larry Yun:

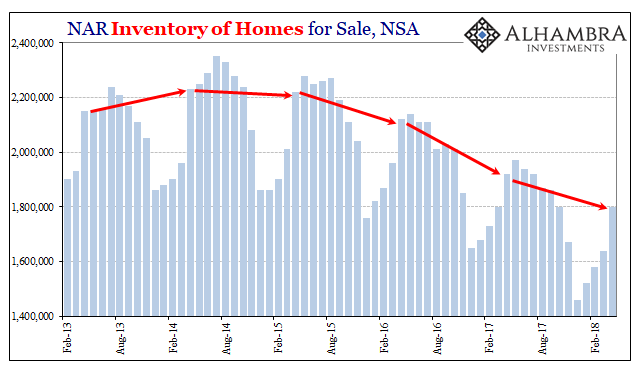

Realtors® say the healthy economy and job market are keeping buyers in the market for now even as they face rising mortgage rates. However, inventory shortages are even worse than in recent years, and home prices keep climbing above what many home shoppers are able to afford.

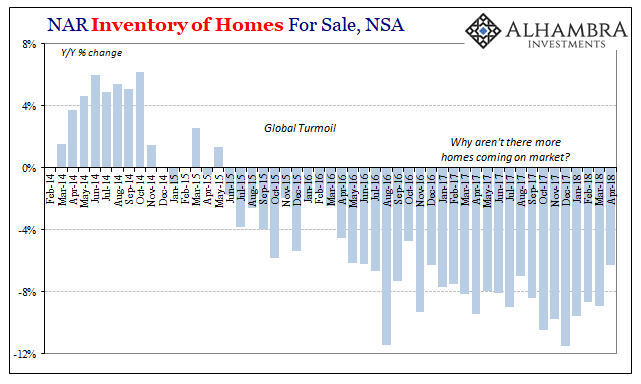

It’s the same problem they have been describing (and we have been pointing out) for years now. The level of resales is stuck, so it must be an inventory problem. The NAR, or any Economists for that matter, never describe why it may be that home owners have grown so reluctant to sell in the first place.

With mortgage rates and home prices continuing to climb, an increase in housing supply is absolutely crucial to keeping affordability conditions from further deterioration. The current pace of price appreciation far above incomes is not sustainable in the long run.

That might propose something like bubble conditions, but unlike the middle 2000’s it’s a segregated one that doesn’t face the entire housing market. Why not?

It’s a pretty clear example of economic bifurcation, the primary issue with this “recovery” in the economy as represented by housing. If you have a job chances are things are going relatively well, you have relatively easy access to financing, and therefore it’s no big deal to go out and buy a home. More than that, you aren’t concerned as much about selling your existing one.

For those who have fallen into the mainstream’s outcast category, neither employed nor technically unemployed, you aren’t going to buy and you sure aren’t going to sell.

The real problem lately, dating back to 2015 and the “rising dollar”, are those in between or on the fence. These are people who may have been more optimistic about the economy given the rhetoric up to 2014. What is now perfectly clear is that this group has grown since that time, and so are afraid to sell what they now possess for the very real risks what that might do if their situation changes for the worse.

Economists claim, as the FOMC did in its minutes released yesterday, some version of the following:

Participants generally agreed that labor market conditions strengthened further during the first quarter of the year. Nonfarm payroll employment posted strong gains, averaging 200,000 per month. The unemployment rate was unchanged, but at a level below most estimates of its longer-run normal rate. Both the overall labor force participation rate and the employment-to-population ratio moved up. The first-quarter data from the employment cost index indicated that the strength in the labor market was showing through to a gradual pickup in wage increases, although the signal from other wage measures was less clear.

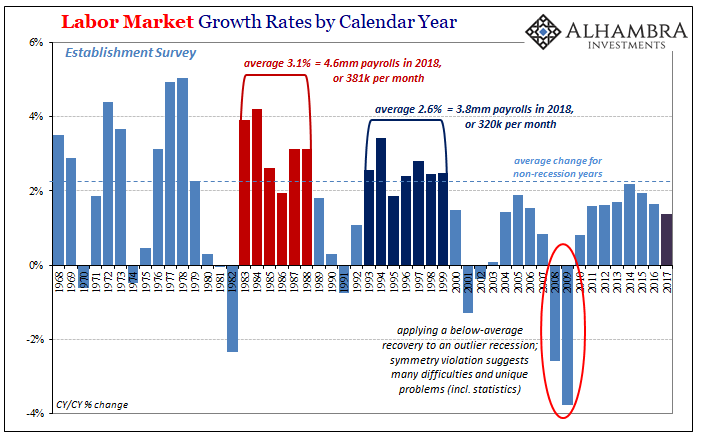

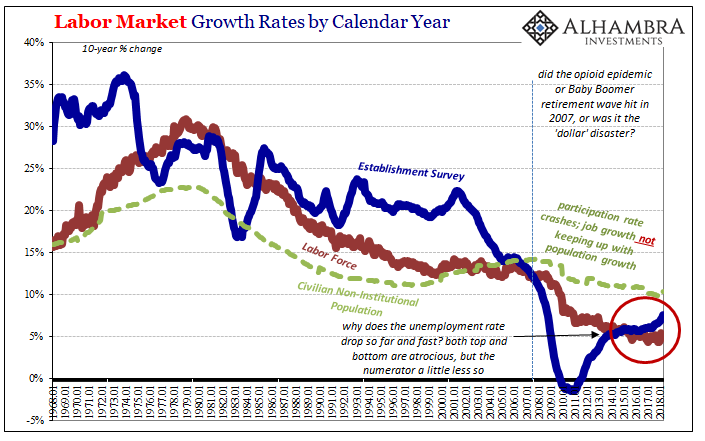

If the labor market were truly all that, then why aren’t people selling their houses and trading up? The primary clue comes at the end of the second sentence; “strong gains” being used to describe 200k per month.

Everyone is fooling themselves into thinking this way, it is such an obvious untruth. That rate of job growth is, in fact, pitiful. The labor market last year was among the worst non-recession years. The lack of inventory is the housing market, the complete housing market, saying exactly that.

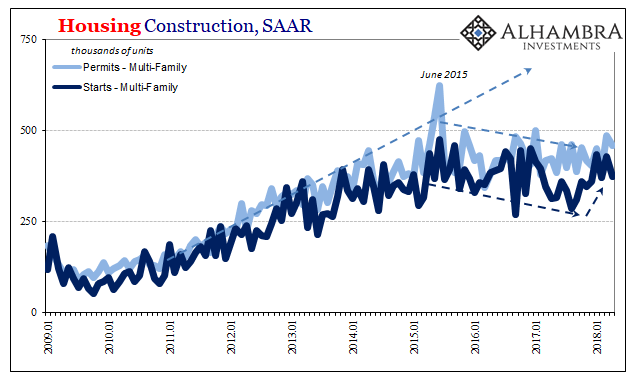

The downturn in multi-family construction merely offers compelling corroboration to the absence of resale inventory. If builders were under the impression that the labor market was really strong, and that especially millennials as young adults were finally ready to participate in it in that way, they would be rushing to construct apartments. These workers, or potential workers, however, are those who fall into that middle category.

These are not the forces of recession. That’s not really the biggest problem facing the overall economy. Rather, all these things show us that the economy shrunk and has never recovered. We are, in essence, continually describing the lack of growth in all these things. It applies to 2018 as much 2014 or any other year since the housing bust.

Last year was supposed to be the year that everything was to change finally, yet despite repeated emphasis on the supposed “strong” economy in truth it just isn’t there; it didn’t show up last year and the farther we go into 2018 the more it becomes clear it isn’t going to this year, either. Inflation hysteria has faded away because you can gloss over 200k in media coverage and NAR press releases, but only for so long.

On that score, all three housing related data series (still) agree.

Stay In Touch