Earlier this week the FOMC published the minutes of its April policy meeting, disappointing “dovish” in them which more properly suggests skepticism about the state of economic affairs. Yesterday, it was the ECB’s turn. Releasing the “Account” of also its April gathering, Europe’s central bank began it by noting Germany’s federal securities. Specifically, it mentions yields falling back on them.

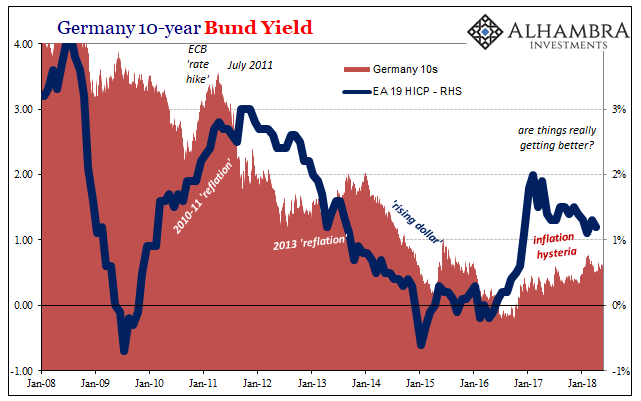

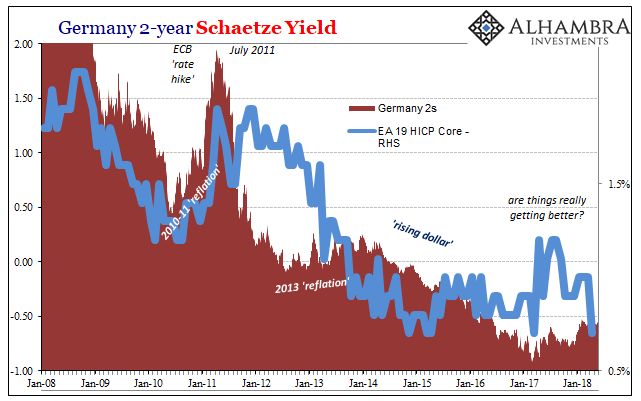

With regard to recent bond market developments, a gradual decline in the ten-year German government bond yield, which started in mid-February, had pushed yields back to levels not far from those observed for most of 2017.

So much for growing evidence of Europe’s boom hysteria. In fact, most of the Account is written to convey growing uncertainties about it all. Germany’s bund market is therefore a very good place to start.

We can do so, however, in a manner in which authorities never do. They quite intentionally frame any discussion about bonds, bunds, or whatever in as short of a perspective as possible. As the quote above demonstrates, that way they can make it seem like progress if yields rise more in 2018 than in 2017 (until even that stops) without having to explain why those same yields remain still nowhere close to 2014, 2011, or normal.

Not being so narrow of focus, instead we can better appreciate just how little German yields have changed in comparison to where they were or would be if there was anything like an economic boom afoot. Sustained economic weakness is therefore consistent not surprising or unexpected.

Germany’s 10s today collapsed by a rather large 12 bps in yield, falling all the way to 0.48%. That’s the lowest since January, unwinding what little of global inflation hysteria had visiting Germany’s debt markets.

As Mario Draghi stated at the start of this year, there really isn’t any current evidence that inflation (or the economy) is picking up. Policymakers, and therefore the media, believe that’s going to happen because they believe that’s what can only happen. As Germany’s debt yields perfectly demonstrate, the markets just aren’t buying it because more rational actors need something more substantial than the same old assumptions.

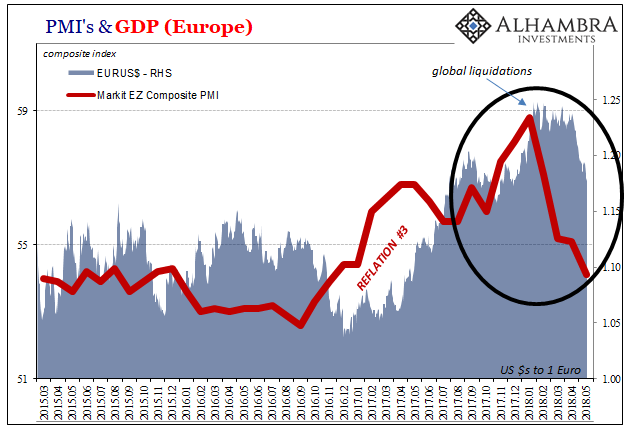

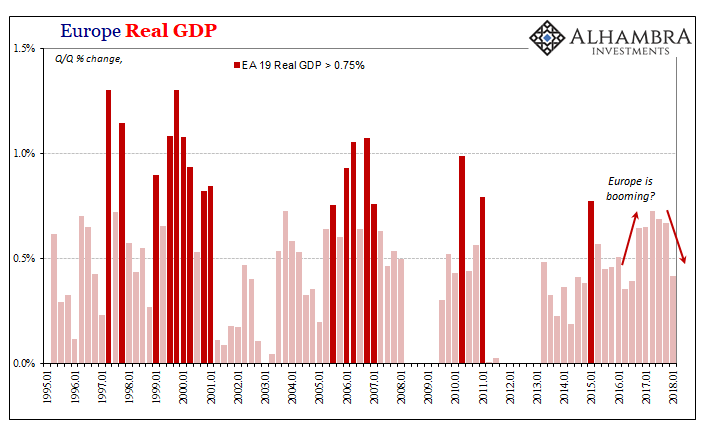

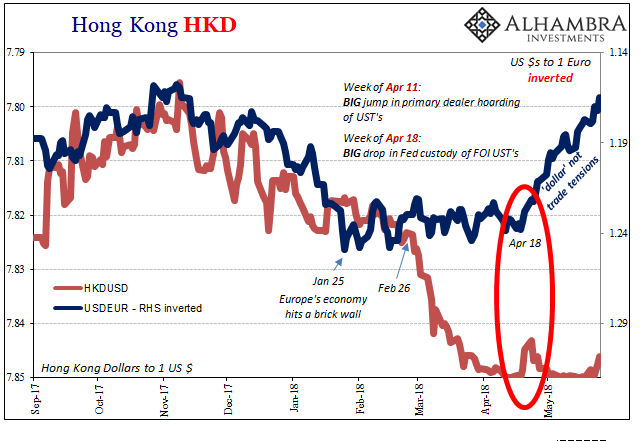

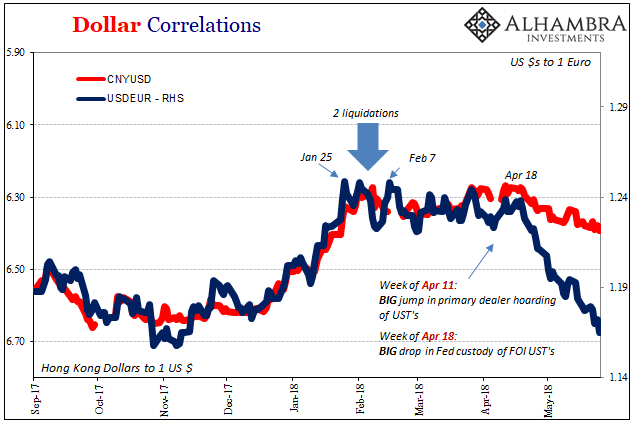

Unlike the American economy which doesn’t yet show clear signs, the European economy at the end of January smacked right into a brick wall of eurodollars. As noted earlier, beginning with the sudden appearance of global liquidations it’s as if Europe’s economy rolled over all at once. Not that it was booming to begin with, meaning that in reality it may be on the wane from a still too-low starting point.

For the first time in a while, the ECB is forced back into discussions of downside risks. This was not supposed to happen. If anything, those were to have completely disappeared (or at least receded as much in reality so that policymakers wouldn’t have to cite them again this cycle) as the small improvement in economic conditions last year were expected to be only the beginning. By now, there should be no concern.

At the same time, it was widely felt that uncertainty surrounding the outlook had increased and caution was seen as warranted in interpreting recent developments, also because the moderation in growth appeared to be broad-based across countries and sectors. A more pronounced weakening of demand, notably related to external factors, could therefore not be ruled out.

I have to agree for once with their blame of “external factors” which are shown quite clearly on the PMI/€ chart included above. The ECB, all-too-predictably, merely mentions “the threat of trade protectionism” as one of them (if not, in their view, the only one).

Despite repeatedly calling the global economy “strong”, which if it was Germany’s debt markets would be adding additional exclamations to a BUND ROUT!!!, and the outlook supposedly brightened by US tax cuts and reform of all things, they can’t help but escape the more obvious:

Overall, the balance of risks to the outlook for global activity, including a more prominent risk of increasing trade tensions and the uncertain implications of the United Kingdom’s withdrawal from the European Union, was considered to remain tilted to the downside.

It may seem a silly and pointless exercise to go through these official statements and accounts. After all, what good have they been? They read like everything else, put together specifically to emphasize the better parts of any incoming data and to downplay what might contradict.

But that’s the point at least in this case. The changed tone of this Account compared to those in the near past is worth some consideration. If the most optimistic of optimists, those like Europe’s central bankers who had made a tiny molehill rise of German yields into a mountain of inflation and normalcy confirmation, the fact that they then turn more cautious and in such broad fashion is potentially significant. If the ECB is getting a little nervous, what does that really say? Central bankers are, as always, the last to figure it out.

And it may be that ECB officials feel secure in doing so because this time unlike in the past they can so easily pass the blame on to “external factors.” Once we drop the trade tensions canard, and more appropriately substitute “rising dollar”, the ECB Account might actually account.

Stay In Touch