A recent poll in Brazil showed that one-third of Brazilians favor “military intervention.” The country had been gripped by a crippling trucker’s strike, the results of which have been almost complete economic shutdown. Intervention, as it is softly termed, would be nothing less than a coup.

The direct cause of the strike is quite simple. Under former President Dilma Rousseff, the state used national oil company Petrobras to subsidize the price of diesel. Monthly adjustments were made, but by and large any oil price fluctuations on global markets made little difference to the country’s vast fleet of trucks snaking their way over highways. It nearly bankrupted the company.

After Rousseff was impeached, her replacement Michel Temer removed the subsidy. Petrobras may be healthier for it, but the price of fuel has skyrocketed for anyone using diesel. Adjustments are often difficult.

But they have been made nearly impossible by what’s going on beyond the cost of keeping Brazil’s trucks, and truckers, moving. Like everywhere else on the planet, Temer’s government claims to have ended the recession and fostered recovery. That’s true but only in the technical sense; there are now positive economic numbers in Brazil after years of only minus signs.

Há dois anos, assumi o governo do Brasil com uma dura missão: retirar o país da sua mais grave recessão, estancar o desemprego, recuperar a responsabilidade fiscal e manter os programas sociais. De fato, tudo isso foi feito.

— Michel Temer (@MichelTemer) May 12, 2018

What the nationwide strike showed was not just the unrest created by uneasy shippers, it was the massive unease that permeates a country whose economy has shrunk. Like Italians, Brazilians are starting to get the notion it isn’t coming back.

“We have watched a flirtation with collective suicide,” wrote rightwing commentator Reinaldo Azevedo, who compared Brazilians heading to the polls in October’s congressional and presidential elections to lemmings heading for a clifftop.

Leftist commentators are equally alarmed. “It is a dangerous moment,” said Laura Carvalho, a professor of economy at the University of São Paulo. “This is related to the economic crisis, the political crisis, the corruption scandals.”

Economic malaise or, dare I write, depression is a pressure vessel. Whatever social divisions will always exist wherever on Earth, they become increasingly untenable where hopelessness sets in without the medicine of opportunity. There’s a reason every political regime seeks robust economic growth, it reduces so many even serious social maladies.

The problem since 2008 is that this far into 2018 politicians keep calling it a recovery when it’s not. That can only make things worse, sowing further mistrust and even, as recent events have shown, the very real possibility of total political breakdown. Brazil is not some extreme outlier, it is merely ahead of the curve.

If one may wonder why India’s central bank chief took to the Financial Times this weekend to mildly plead with the Federal Reserve to do something (though that something would be just as ineffectual and irrelevant as anything the Fed has done or might do) about the world’s recent flaring “dollar” problems, this would be the prime example. In public, they all say recovery; in private, authorities might still use the term with each other but their fingers are crossed, their brows are furled, and they are surely covered in sweat while forming the word on their lips.

Many officials particularly in EM nations understand the peril. In the US, we were largely spared the wrath of the “rising dollar”, taking only a near recession downturn for that cause. But it’s something of a mistake to think we were lucky in that regard; it was merely a continuation of an eleven-year monetary saga without an end yet in sight. We took our lumps in 2008 and early 2009.

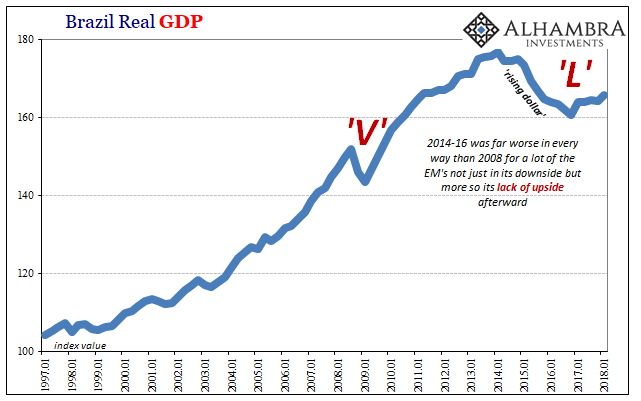

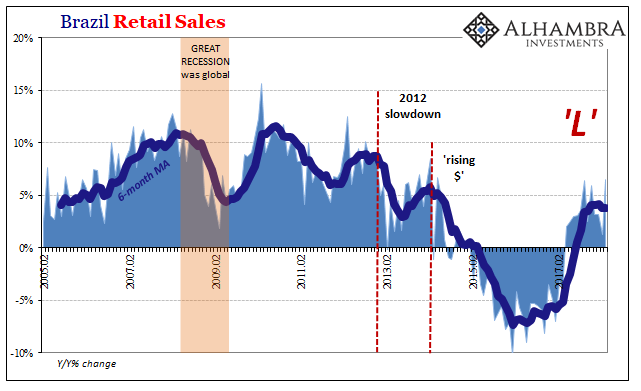

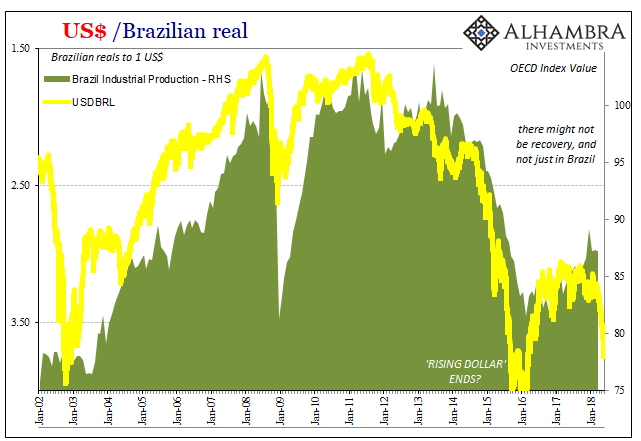

Many if not most EM economies survived the Great “Recession” with no prolonged collapse. They recovered quickly, but it didn’t last. By 2012, after the big eurodollar event in 2011, things were already coming apart. Brazil like China went through a noticeable rough spot in 2013, but that merely forewarned what was to come. To these places, what happened in 2015-16 was for them their 2008.

The statistics so far this year bear that out. While positive for the most part, again that is meaningless especially when compared to several years of serious contraction. A small rebound after a big drop is practically indistinguishable from that drop. This, quite naturally, appears to be the way Brazilians are feeling about the “recovery”, a sentiment they share with people all over the world – at least with those who are not currently sitting in some elected office.

From GDP to Industrial Production to Retail Sales, there is every indication that Brazil’s economy has seen its best of a rebound; and it wasn’t much. Like GDP (+1.2% year-over-year in Q1 2018, following +2.1% in Q4 2017 and +1.4% last Q3) there is the growing sense that things may already be slowing again after such a brief and small reprieve.

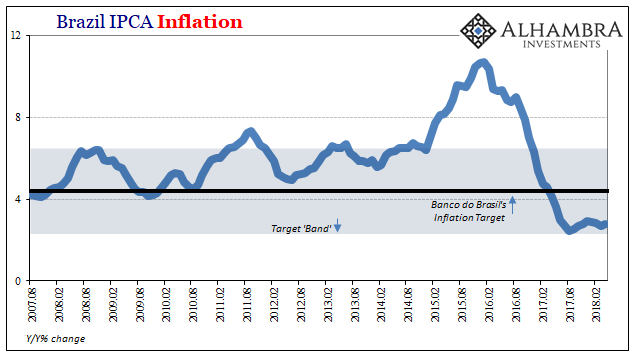

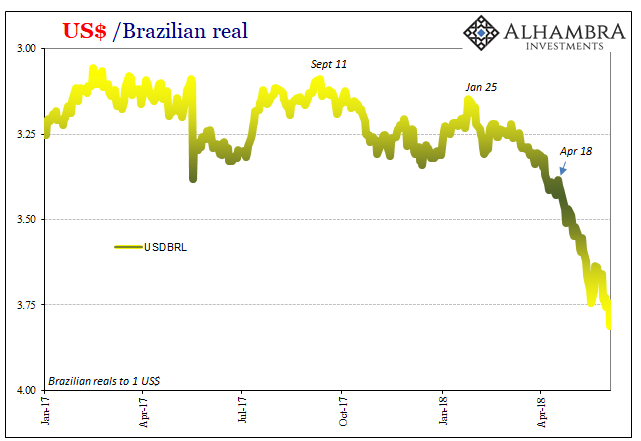

That all starts with, as always, the “dollar.” The one thing that doesn’t yet plague Brazil’s system is high consumer price inflation. During the real’s crash in 2014 and 2015, consumer prices necessarily skyrocketed as the cost of funding the country’s “dollar short” had to have been passed on to Brazil’s workers and consumers.

With this particular currency once again leading the renewed EM crisis, this small positive isn’t likely to be the case in the coming months. There is every possibility that things could go from really bad to worse as BRL ticks back down toward 4.00, and the world’s Economists struggle to define let alone explain it.

And the media in the developed world will dismiss all of this as Brazil being Brazil, South America’s basket case reverting to type. The siren song of globally synchronized growth has gripped all commentary, and they aren’t about to let it go now. Certainly not for the other side of the eurodollar when FOMC officials who despite their entire track record assure everyone there couldn’t possibly be anything wrong in banks, banking, and funding. For them, there is no eurodollar system. For everyone who lives on Planet Earth, there is only continuing, escalating fallout from that which still does not officially exist.

Stay In Touch